Search Results for: "sas institute"

What is IP For? Experiments in Lay and Expert Perceptions

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Answering the Call — Pro Se Assistance at the USPTO

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Broad Estoppel After Failed IPR: What Prior Art “could have been found by a skilled searcher’s diligent search?”

by Dennis Crouch

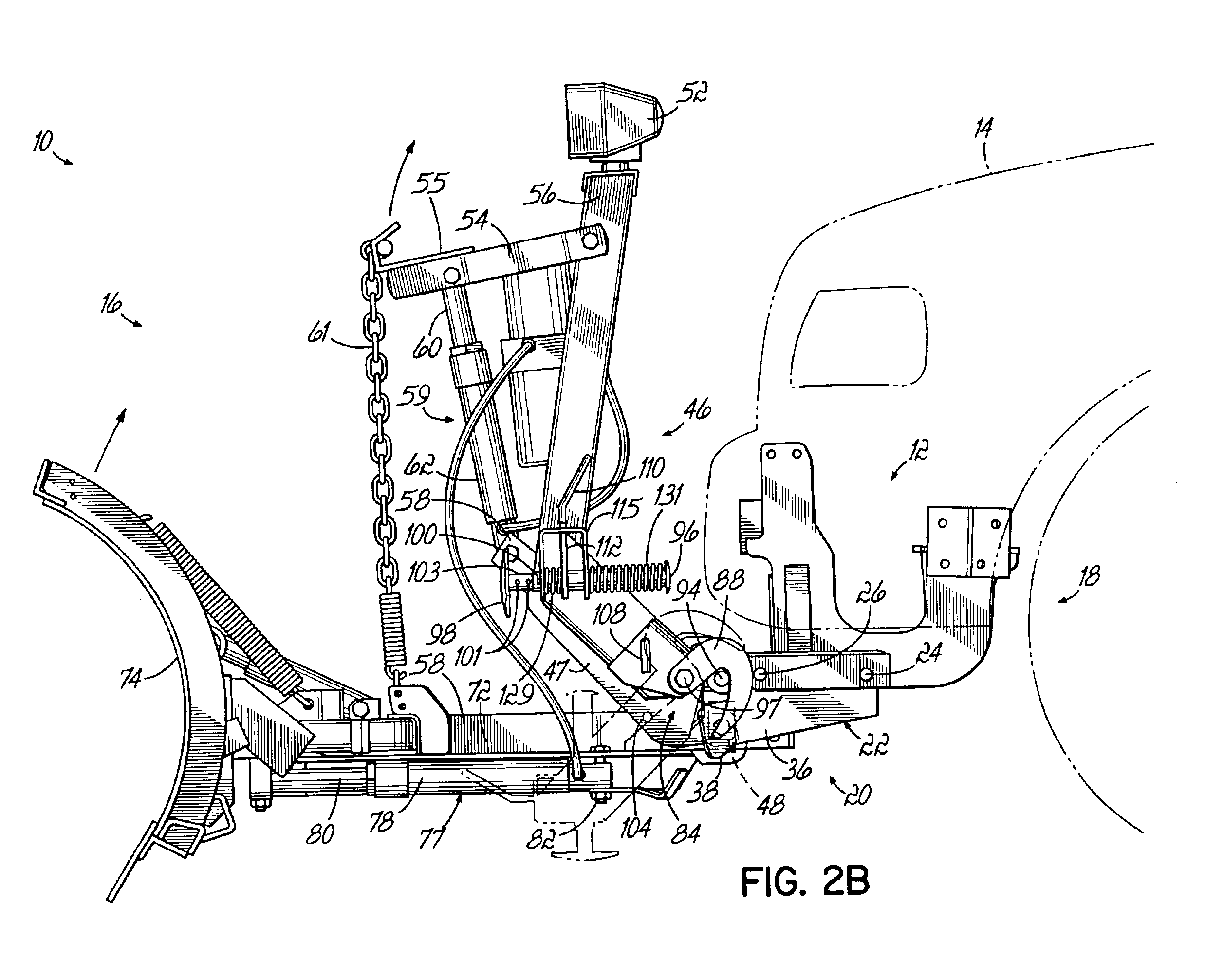

Douglas Dynamics v. Meyer Prods (W.D. Wisc 2017) [2017-04-18 (68) Order re post IPR invalidity defenses]. After Douglas sued Meyer for infringing its U.S. Patent No. 6,928,757 (Snowplow mounting assembly), Meyer petition for inter partes review -- alleging that several of the claims were invalid. Although the "director" iniated the review, the PTAB eventually sided with the patentee - reaffirming the validity of the claims.

After Douglas sued Meyer for infringing its U.S. Patent No. 6,928,757 (Snowplow mounting assembly), Meyer petition for inter partes review -- alleging that several of the claims were invalid. Although the "director" iniated the review, the PTAB eventually sided with the patentee - reaffirming the validity of the claims.

Back at the district court, Douglass asked the court to apply the estoppel provisions that of Section 315(e)(e):

The petitioner in an inter partes review ... that results in a final written decision under section 318(a) . . . may not assert . . . in a civil action arising [under the patent laws] . . . that the claim is invalid on any ground that the petitioner raised or reasonably could have raised during that inter partes review.

35 U.S.C. § 315(e)(2). The question for the district court here, was the scope of estoppel - what constitutes grounds that were "raised or reasonably could have [been] raised" during the IPR. Here, the court took a position for fairly strong estoppel:

If the defendant pursues the IPR option, it cannot expect to hold a second-string invalidity case in reserve in case the IPR does not go defendant’s way. In many patent cases, particularly those involving well-developed arts, there is an abundance of prior art with which to make out an arguable invalidity case, so it would be easy to have a secondary set of invalidity contentions ready to go. The court will interpret the estoppel provision in § 315(e)(2) to preclude this defense strategy. Accordingly, the court will construe the statutory language “any ground that the petitioner . . . reasonably could have raised during that inter partes review” to include non-petitioned grounds that the defendant chose not to present in its petition to PTAB.

In Shaw Industries Group, Inc. v. Automated Creel Systems, Inc., 817 F.3d 1293 (Fed. Cir.), the Federal Circuit wrote in dicta that no estoppel should apply to grounds that were petitioned, but not instituted. The Wisconsin court here suggested some potential problems with that outcome, but decided to follow the CAFC's lead, writing:

So until Shaw is limited or reconsidered, this court will not apply § 315(e)(2) estoppel to [petitioned but] non-instituted grounds, but it will apply § 315(e)(2) estoppel to grounds not asserted in the IPR petition, so long as they are based on prior art that could have been found by a skilled searcher's diligent search.

What this means for the defendant here is that the only 102/103 arguments that it gets to raise are ones already deemed total failures by the PTAB - and thus are unlikely winners before a district court.

= = = = =

Of some importance, the PTAB's final written decision was released in November 2016. For estoppel purposes, that final decision is all that is required for estoppel to kick-in. However, the case currently on appeal to the Federal Circuit -- already giving the defendant its second bite at the apple.

= = = =

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Objective Indicia of Non-Obviousness Must be Tied to Inventive Step

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

CAFC: Prior Judicial Opinions Do Not Bind the PTAB

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

TC Heartland LLC v. Kraft Foods Oral Arguments.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Affirming Arbitration Award

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Chan v. Yang: Can the Federal Circuit Continue to Affirm Without Opinion?

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Whether a Patent Right is a Public Right

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

PTO Director Michelle Lee?

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Supreme Court 2017 – Patent Preview

by Dennis Crouch

A new Supreme Court justice will likely be in place by the end of April, although the Trump edition is unlikely to substantially shake-up patent law doctrine in the short term.

The Supreme Court has decided one patent case this term. Samsung (design patent damages). Five more cases have been granted certiorari and are scheduled to be decided by mid June 2017. These include SCA Hygiene (whether laches applies in patent cases); Life Tech (infringement under 35 U.S.C. § 271(f)(1) for supplying single component); Impression Products (using patents as a personal property servitude); Sandoz (BPCIA patent dance); and last-but-not-least TC Heartland (Does the general definition of "residence" found in 28 U.S.C. 1391(c) apply to the patent venue statute 1400(b)).

Big news is that the Supreme Court granted writs of certiorari in the BPCIA dispute between Sandoz and Amgen. The BPCIA can be thought of as the 'Hatch Waxman of biologics' - enacted as part of ObamaCare. The provision offers automatic market exclusivity for twelve years for producers of pioneer biologics. Those years of exclusivity enforced by the FDA - who will not approve a competitor's expedited biosimilar drug application during the exclusivity period. The statute then provides for a process of exchanging patent and manufacturing information between a potential biosimilar producer and the pioneer - known as the patent dance. The case here is the Court's first chance to interpret the provisions of the law - the specific issue involves whether the pioneer (here Amgen) is required to 'dance.' [Andrew Williams has more @patentdocs]

A new eligibility petition by Matthew Powers in IPLearn-Focus v. Microsoft raises eligibility in a procedural form - Can a court properly find an abstract idea based only upon (1) the patent document and (2) attorney argument? (What if the only evidence presented supports eligibility?). After reading claim 1 and 24 (24 is at issue) of U.S. Patent No. 8,538,320, you may see why the lower court bounced this. Federal Circuit affirmed the district court's ruling without opinion under Federal Circuit Rule 36 and then denied IPLF's petition for rehearing (again without opinion).

1. A computing system comprising:

a display;

an imaging sensor to sense a first feature of a user regarding a first volitional behavior of the user to produce a first set of measurements, the imaging sensor being detached from the first feature to sense the first feature, the first feature relating to the head of the user, and the first set of measurements including an image of the first feature, wherein the system further to sense a second feature of the user regarding a second volitional behavior of the user to produce a second set of measurements, the second feature not relating to the head of the user; and

a processor coupled to the imaging sensor and the display, the processor to:

analyze at least the first set and the second set of measurements; and determine whether to change what is to be presented by the display in view of the analysis.

24. A computing system as recited in claim 1, wherein the system capable of providing an indication regarding whether the user is paying attention to content presented by the display.

1. 2016-2016 Decisions:

- Design Patent Damages: Samsung Electronics Co. v. Apple Inc., No 15-777 (Total profits may be based upon either the entire product sold to consumers or a component); GVR order in parallel case Systems, Inc. v. Nordock, Inc., No. 15-978. These cases are now back before the Federal Circuit for the job of explaining when a component

2. Petitions Granted:

- Argued - Awaiting Decision: SCA Hygiene Products Aktiebolag v. First Quality Baby Products, LLC, No. 15-927 (laches in patent cases)

- Argued - Awaiting Decision: Life Technologies Corporation, et al. v. Promega Corporation, No. 14-1538 (infringement under 35 U.S.C. § 271(f)(1) for supplying single component)

- Briefing: Impression Products, Inc. v. Lexmark International, Inc., No. 15-1189 (unreasonable restraints on downstream uses)

- Briefing: Sandoz Inc. v. Amgen Inc., et al., No. 15-1039 (Does the notice requirement of the BPCIA create an effective six-month exclusivity post-FDA approval?)

- Briefing: TC Heartland LLC v. Kraft Food Brands Group LLC, No 16-341 (Does the general and broad definition of "residence" found in 28 U.S.C. 1391(c) apply to the patent venue statute 1400(b))

3. Petitions with Invited Views of SG (CVSG):

4. Petitions for Writ of Certiorari Pending:

- Is it a Patent Case?: Boston Scientific Corporation, et al. v. Mirowski Family Ventures, LLC, No. 16-470 (how closely must a state court "hew" federal court patent law precedents?) (Appeal from MD State Court)

- Anticipation/Obviousness: Google Inc., et al. v. Arendi S A.R.L., et al., No. 16-626 (can "common sense" invalidate a patent claim that includes novel elements?) (Supreme Court has requested a brief in response)

- Civil Procedure - Final Judgment: Johnson & Johnson Vision Care, Inc. v. Rembrandt Vision Technologies, L.P., No. 16-489 (Reopening final decision under R.60).

- Anticipation/Obviousness: Enplas Corporation v. Seoul Semiconductor Co., Ltd., et al., No. 16-867 ("Whether a finding of anticipation under 35 U.S.C. § 102 must be supported by findings that each and every element of the subject patent claim is disclosed in the prior art?")

- Post Grant Admin: Oil States Energy Services, LLC v. Greene's Energy Group, LLC, et al., No. 16-712 ("Whether inter partes review ... violates the Constitution by extinguishing private property rights through a non-Article III forum without a jury.") [oilstatespetition]

- Eligibility: IPLearn-Focus, LLC v. Microsoft Corp., No. 16-859 (evidence necessary for finding an abstract idea)

- Post Grant Admin: SightSound Technologies, LLC v. Apple Inc., No. 16-483 (Can the Federal Circuit review USPTO decision to initiate an IPR on a ground never asserted by any party)

- Is it a Patent Case?: Big Baboon, Inc. v. Michelle K. Lee, No. 16-496 (Appeal of APA seeking overturning of evidentiary admission findings during reexamination - heard by Federal Circuit or Regional Circuit?)

- Laches: Medinol Ltd. v. Cordis Corporation, et al., No. 15-998 (follow-on to SCA); Endotach LLC v. Cook Medical LLC, No. 16-127 (SCA Redux); Romag Fasteners, Inc. v. Fossil, Inc., et al, No. 16-202 (SCA Redux plus TM issue)

- Eligibility and CBM: DataTreasury Corporation v. Fidelity National Information Services, Inc., No. 16-883 (I have not seen the petition yet, but underlying case challenged whether (1) case was properly classified as CBM and (2) whether PTAB properly ruled claims ineligible as abstract ideas) (Patent Nos. 5,910,988 and 6,032,137).

5. Petitions for Writ of Certiorari Denied or Dismissed:

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Post-PTO Trials: Party must Prove Injury-in-Fact for Appellate Standing

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Separation of Powers Restoration Act

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Goodbye E.D.Texas as a Major Patent Venue

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Judging Ex Parte Cases

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Is it Obvious to Combine Five References?

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Economic Nationalism and the U.S. Patent System

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Arbitrating Attorney Fees: No Appeal?

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Patentlyo Bits and Bytes by Anthony McCain

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.