by Dennis Crouch

On September 30, 2024, the Supreme Court held its long conference, and considered whether to grant certiorari in a number of pending patent cases, including the eligibility-focused petition in Eolas v. Amazon. As we await the outcome of that conference, I wanted to highlight another new elitibility petition. This one in Plotagraph v. Lightricks.

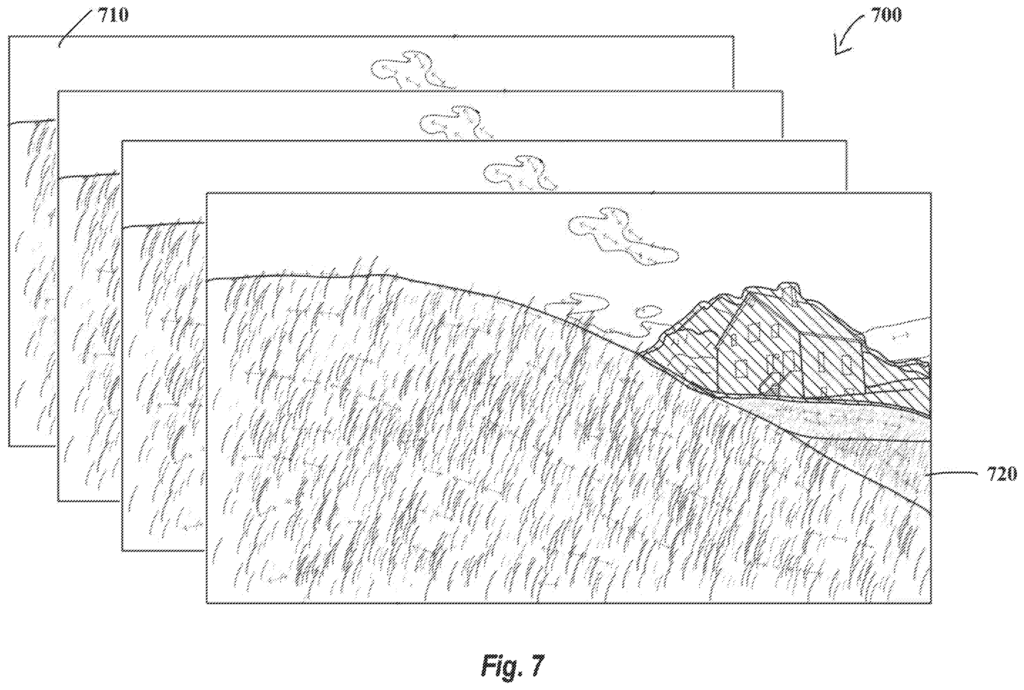

Plotagraph, Inc. along with inventors Troy Plota and Sascha Connelly petitioned the court - seeking review of a non-precedential Federal Circuit decision that invalidated five of their patents related to digital animation technology. U.S. Patent Nos. 10,346,017, 10,558,342, 10,621,469, 11,182,641, and 11,301,119. The patented invention allows users to animate portions of digital still photos or video frames by selecting and shifting sets of pixels to simulate motion. For example, the technology could be used to make a waterfall in a still photo appear to be flowing. The Federal Circuit affirmed a district court decision that found these patents ineligible under § 101, concluding that they were directed to the abstract idea of digital animation and lacked an inventive concept.