The copyright dispute over Ed Sheeran's song "Thinking Out Loud" has made its way to the Supreme Court's doorstep. The petition raises questions about judicial deference to administrative interpretations and the scope of copyright protection for musical compositions under the 1909 Copyright Act. In the case, the Second Circuit had sided with Sheeran -- affirming dismissal of the infringement claim based largely on a technical limitation of pre-1976 copyright law. Structured Asset Sales, LLC v. Sheeran.

- Rick Beato has a great analysis of the two songs: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0kt1DXu7dlo

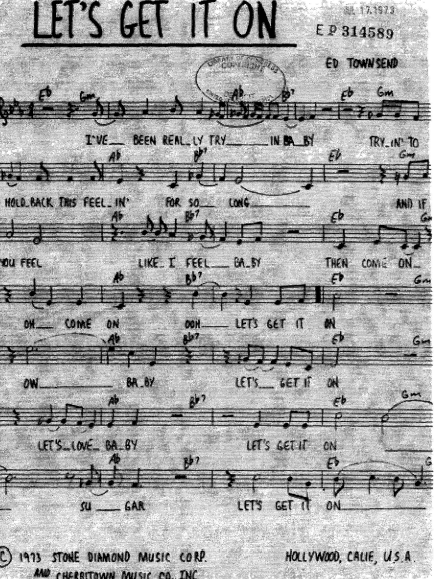

The underlying dispute centers on allegations that Sheeran's Grammy-winning "Thinking Out Loud" (2014) infringes the copyright of Marvin Gaye and Ed Townsend's "Let's Get It On" (1973). Structured Asset Sales (SAS) owns a partial interest in Townsend's share and contends that Sheeran copied protected elements from the iconic soul classic.

The Second Circuit's decision hinged on the fact that the copyright was pre-1976. Under the 1909 Copyright Act, the scope of copyright protection extends only to the elements contained in the "deposit copy" submitted to the Copyright Office at registration. In this case, that meant only the elements in the handwritten sheet music deposited in 1973, not the additional musical elements found in Gaye's sound recording.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.