Tag Archives: design patent

Utility and Design Patents – Up Again for 2017

Impact of the 15-year Design Patent Term

First Post-Samsung Design Patent Damages Verdict

Design Patents 2017

Design Patents Per Fiscal Year: New High Expected for FY2017

Apple Samsung: Federal Circuit Remands Design Patent Damages Decision to District Court

Samsung v. Apple: Back before the Federal Circuit on Design Patent Damages

Samsung v. Apple: Design Patent Damages May be Limited to Components

Digital Trademark and Design Patent Infringement

Design Patent Damages at the Supreme Court

Design Patent Claim Construction: More from the Federal Circuit

Guest post by Sarah Burstein, Associate Professor of Law at the University of Oklahoma College of Law.

Sport Dimension, Inc. v. Coleman Co., Inc. (Fed. Cir. April 19, 2016) Download Opinion

Panel: Moore, Hughes, Stoll (author)

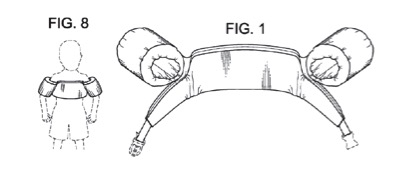

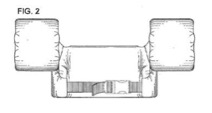

Coleman accused Sport Dimension of infringing U.S. Patent No. D623,714 (the “D’714 patent”), which claims the following design for a “Personal Flotation Device”:

The district court construed the claim as: “The ornamental design for a personal flotation device, as shown and described in Figures 1–8, except the left and right armband, and the side torso tapering, which are functional and not ornamental.” The court, like many other courts and a number of commentators, interpreted the Federal Circuit’s 2010 decision in Richardson v. Stanley Works as requiring courts to “factor out” functional parts of claimed designs. Coleman moved for entry of judgment of noninfringement and appealed the claim construction (along with another issue not relevant to this discussion).

After Coleman’s appeal was docketed, the Federal Circuit disavowed the “factoring out” rule that many had read in Richardson. As discussed previously on this blog, in Apple v. Samsung and again in Ethicon v. Covidien, the court insisted that Richardson did not, in fact, require the elimination of functional elements from design patent claims.

Following this new interpretation of Richardson, the Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s construction of Coleman’s claim. The court stated, for the third time in a year, that district courts should not eliminate portions of claimed designs during claim construction. So it seems that the Federal Circuit’s retreat from Richardson is complete—if that weren’t clear already.

And, for the first time I’m aware of, the court actually explained how it determined whether something is “functional” for the purposes of claim construction. It’s been clear for a while that the court was using a more expansive concept of “functionality” in the context of claim construction than it was using for validity. (For more on this issue, see this recent LANDSLIDE article by Chris Carani.) However, the court hasn’t seemed to acknowledge that disconnect or explain how courts should analyze functionality in the claim construction context. In this case, the court did both. The Federal Circuit stated that the Berry Sterling factors, although “introduced…to assist courts in determining whether a claimed design was dictated by function and thus invalid, may serve as a useful guide for claim construction functionality as well.” (Those factors, discussed here, are very similar to the factors used by courts to determine whether a design is invalid as functional in the trademark context. For more on the trademark test and how it differs from the current design patent test for validity, see here.) Applying the Berry Sterling factors to the facts of this case, the court affirmed the district court’s conclusion that the armbands and tapering were functional.

So in Sport Dimension, it is clear that the Federal Circuit thinks it is important to determine whether an “element” or “aspect” (the court uses those words as synonyms) of a design is functional. And it is very clear that courts are not supposed to completely remove functional “elements” or “aspects” from design patent claims as a part of claim construction. But what are courts supposed to do? Here is what the court said:

We thus look to the overall design of Coleman’s personal flotation device disclosed in the D’714 patent to determine the proper claim construction. The design includes the appearance of three interconnected rectangles, as seen in Figure 2. It is minimalist, with little ornamentation. And the design includes the shape of the armbands and side torso tapering, to the extent that they contribute to the overall ornamentation of the design. As we discussed above, however, the armbands and side torso tapering serve a functional purpose, so the fact finder should not focus on the particular designs of these elements when determining infringement, but rather focus on what these elements contribute to the design’s overall ornamentation.

It’s not at all clear what the court is trying to say here, especially in the highlighted portion (emphasis mine). It seems that perhaps the court is trying to say that, in analyzing infringement, the factfinder should focus on the overall appearance of the claimed design. But if that is what the court meant, then this “claim construction” frolic adds nothing—the infringement test already requires the factfinder to look at the actual claimed design, as opposed to the general design concept.

This portion of the decision also seems to be in some conflict with the court’s decision in Ethicon. In Ethicon, as here, the district court eliminated all the functional portions of the claimed design. Unlike this case, the district court in Ethicon said that all the elements were functional and, thus, the claim had no scope. The Federal Circuit reversed, stating:

[A]lthough the Design Patents do not protect the general design concept of an open trigger, torque knob, and activation button in a particular configuration, they nevertheless have some scope—the particular ornamental designs of those underlying elements.

So Ethicon says that factfinders must look at the “particular ornamental designs” of functional elements. Sport Dimension says they “should not focus on the particular designs of [functional] elements.” These statements could potentially be reconciled by drawing a distinction between the “particular design” of an element/feature and the “particular ornamental design.” But it’s not at all clear what that distinction might be—or whether it makes sense to draw such a distinction at all.

More importantly, it’s not clear what, exactly, the Federal Circuit hopes to gain by making district courts go through this rigmarole. In this case, the accused product looks nothing like the claimed design, as can be seen from these representative images:

Claimed Design

Accused Product

Yes, they both have armbands with somewhat similar shapes and some tapering at the torso. But the overall composition of design elements is strikingly different. You don’t need to “factor out” anything or “narrow” the claim to reach the conclusion that these designs are plainly dissimilar. (The same was true, by the way, of the facts in Richardson.) Even for designs that are not plainly dissimilar, the Egyptian Goddess test for infringement should serve to narrow claims appropriately where elements are truly functional because one would expect those elements to appear in the prior art. So once again, one is forced to ask what the Federal Circuit is trying to accomplish with these “claim construction functionality” rules—and whether the game is worth the candle.