Patently-O Blog: Terms of Use

Updated December 1, 2016

Although I hope you are finding this blog useful and enjoyable, I want to make sure that our respective rights and responsibilities related to the blog are clear. The following is intended to be a legally enforceable contract. You should be careful to note that you are assenting to the contract by accessing the blog more than once. Each subsequent intentional access of the blog likewise will serve as assent to the contract.

Patently-O LLC (PO) offers this blog as a service to you subject to the following terms and conditions of use (“Terms”). By accessing the Patently-O blog or its related services (collectively the “Blog”) a second and/or subsequent time, and in consideration for the blog service that PO provides you (including at least access to information found on the blog and allowing your user comments), you agree to abide by these Terms. Alternative acceptable forms of assent/obligation include your creating content for the Blog; contributing content to the Blog; and signing-up for email delivery of content from the Blog.

The Blog is usually hosted at www.patentlyo.com (formerly patentlaw.typepad.com). As introduced above, the related services of the Blog include websites that are served under the patentlyo.com domain such as the Patent Law Journal (www.patentlyo.com/lawjournal) and Patent Law Jobs site (www.patentlyo.com/jobs). Another related service is the daily e-mail service that distributes Blog content via email.

1. Rights in the Content You Submit

Any and all works of authorship copyrightable by you and posted by you (Content) to the Blog are submitted under a fully paid-up license to PO. Under this license, you permit PO to copy, distribute, display and perform your Content, royalty-free and via any media. You also permit PO to distribute derivative works of your Content and to grant both explicit and implicit sublicenses to anyone. The fully paid-up license gives PO the right to earn money from your Content in any way that PO sees fit — including posting it in a password protected site, publishing it in a book, making a movie, translating it to Russian, or making jokes about the Content.

At PO’s discretion, this license may permit RSS aggregators to copy, distribute, display and perform any Content that you submit. Further, your submission does not create any obligation on PO to publish your submitted Content or to retain your Content.

2. Conduct

I believe deeply in free speech. However, this is PO’s Blog, and PO reserves the right to remove any content that you may post. As a general matter, PO often tries to make some attempt to remove content that is illegal, obscene, defamatory, threatening, infringing of intellectual property rights, invasive of privacy or otherwise injurious or objectionable to PO. However, PO’s filters are far from perfect – PO disclaims any responsibility for poor filtering.

You may not use PO’s name or the name of Dennis Crouch or any other author to endorse or promote any product, opinion, cause or political candidate. Representation of your personal opinions as endorsed by PO is strictly prohibited.

By posting content to the Blog, you warrant and represent that you either own or otherwise control all of the rights to that content, including, without limitation, all the rights necessary for you to provide, post, upload, input or submit the content, or that your use of the content is a protected fair use. You agree that you will not knowingly and with intent to defraud provide material and misleading false information. You represent and warrant also that the content you supply does not violate these Terms, and that you will indemnify and hold PO and Dennis Crouch harmless for any and all claims resulting from content you supply.

You acknowledge that PO does not necessarily pre-screen or regularly review posted content, but that PO shall have the right to remove or modify in PO’s sole discretion any content that PO considers to violate these Terms or for any other reason. PO may also delegate this authority or any other rights or responsibilities of this contract.

You agree that all content posted to the Blog is the sole responsibility of the individual who originally posted the content. You agree, also, that all opinions expressed by users of this site are expressed strictly in their individual capacities, and not as representatives of PO, its owners or employees.

You agree that neither PO nor Dennis Crouch will be liable, under any circumstances and in any way, for any errors or omissions, loss or damage of any kind incurred as a result of use of any content posted on this site. You agree to evaluate and bear all risks associated with the use of any content, including any reliance on the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of such content.

3. Disclaimer of Warranties and Limitation of Liability

This site is provided on an “as is” and “as available” basis. Neither PO nor Dennis Crouch make any representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, as to the site’s operation or the information, content or materials included on this site. To the full extent permissible by applicable law, PO & Dennis Crouch hereby disclaim all warranties, express or implied, including but not limited to implied warranties of merchantability and fitness for any particular purpose. Neither PO nor Dennis Crouch will be liable for any damages of any kind arising from the use of or inability to use this site. You expressly agree that you use this site solely at your own risk.

If you distribute any Blog content to any third party, you agree to warrant that the third party has agreed to all Terms.

These posts are not legal advice and are written for the eyes of other patent attorneys and patent agents. This site belongs to PO. These posts are not edited by Dennis Crouch’s employers or their clients and, as such, cannot be so attributed. Similarly, this Blog and these posts are not works for hire, but are written entirely outside of the scope of Dennis Crouch’s employment. To the extent that any of Dennis Crouch’s employers’ resources have been used to maintain the site, that use was done with full understanding that a limited amount of personal computer use is acceptable. Views expressed here should be double-checked for accuracy and current applicability. Don’t go playing the stock market based on these posts either — because these post do not provide financial advice.

4. Privacy Policy

The nature of blogging is to reach a public audience. Please be aware that any information that you submit to PO whether through forms or email, including personally identifiable information, may be publicly displayed on the Blog, or on websites within or not within our control. If you don’t want others to see such information, don’t submit it. PO may publicly display the IP addresses of visitors and contributors the Blog. PO may use your IP address to help diagnose problems with our server, to tailor site content and to format the site and software to user needs, and to generate aggregate statistical reports. PO may use aggregate visitor data to prepare publicly displayed reports regarding the traffic on individual blogs, site popularity rankings, and referrers that visitors use to access individual blogs.

5. Modification of These Terms of Use

PO reserves the right to change, at any time, at PO’s sole discretion, the Terms under which these Services are offered. You are responsible for regularly reviewing these Terms (Monthly). Your continued use of the Services constitutes your agreement to all such Terms and their revisions.

6. Copyright

The material here is copyrighted. Anyone should feel free to copy a short snippets from the Blog, so long as you attribute the material source. A sample attribution follows: Dennis Crouch, Patently-O available at https://patentlyo.com. Attribution is required under this contract even if the use would be considered a “fair use.” Contact PO (via dcrouch@patentlyo.com) if you want to copy an entire post or a series of posts.

7. Reader Addendum

Anyone who reads content from the site more than twice agrees to not charge PO or Dennis Crouch with any violation of copyright, Lanham Act, patent, defamation, libel, or fraud claim based wholly or partially on any aspect of this Site or Blog. If you do have a problem with anything posted on the site or feel that you have an ownership claim to anything on the site, please contact PO immediately.

8. Severability

If portions of these Terms are found unenforceable, the remainder of the contract is still enforceable.

9. DMCA Notice

If you believe that your work has been copied in a way that constitutes copyright infringement, please provide our Copyright Agent the following information:

- 16.1: an electronic or physical signature of the person authorized to act on behalf of the owner of the copyright interest;

- 16.2: a description of the copyrighted work that you claim has been infringed, including the URL (web page address) of the location where the copyrighted work exists or a copy of the copyrighted work;

- 16.3: a description of where the material that you claim is infringing is located on the site, including the URL;

- 16.4: your address, telephone number, and email address;

- 16.5: a statement by you that you have a good faith belief that the disputed use is not authorized by the copyright owner, its agent, or the law; and

- 16.6: a statement by you, made under penalty of perjury, that the above information in your Notice is accurate and that you are the copyright owner or authorized to act on the copyright owner’s behalf.

PO’s Agent for Notice of claims of copyright infringement can be reached as follows:

- by mail: Dennis Crouch, 4109 Watertown Pl, Columbia MO 65203

- by phone: 573.289.6361

- by email: dcrouch@patentlyo.com

After years of high-profile legal battles, NTP and Research-in-Motion (RIM) have reportedly settled their patent dispute over RIM’s BlackBerry system. According to the

After years of high-profile legal battles, NTP and Research-in-Motion (RIM) have reportedly settled their patent dispute over RIM’s BlackBerry system. According to the  MedImmune v. Genentech* (Supreme Court 2006).

MedImmune v. Genentech* (Supreme Court 2006).  Applied Medical Resources Corp. v. United States Surgical Corp. (Fed. Cir. 2006).

Applied Medical Resources Corp. v. United States Surgical Corp. (Fed. Cir. 2006).  Aspex Eyewear v. Miracle Optics (Fed. Cir. 2006).

Aspex Eyewear v. Miracle Optics (Fed. Cir. 2006).  by Richard Carden

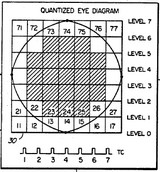

by Richard Carden Sicom Systems v. Agilent (Fed. Cir. 2005).

Sicom Systems v. Agilent (Fed. Cir. 2005).  eBay v. MercExchange (on petition for certiorari).

eBay v. MercExchange (on petition for certiorari).  At the district court, Enzo’s patent, covering DNA probes for hybrodizing N. gonorrhoeae, was held invalid under the on sale bar. Specifically, the district court found that the claimed invention had been offered for sale before the critical date — more than one year before the patent application was filed.

At the district court, Enzo’s patent, covering DNA probes for hybrodizing N. gonorrhoeae, was held invalid under the on sale bar. Specifically, the district court found that the claimed invention had been offered for sale before the critical date — more than one year before the patent application was filed.  U.S. Philips v. International Trade Commission (Fed. Cir. 2005)

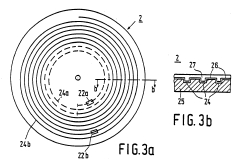

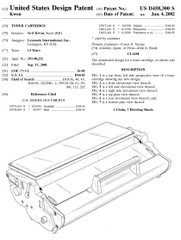

U.S. Philips v. International Trade Commission (Fed. Cir. 2005) Arizona Cartridge Remanufacturers Assn. v. Lexmark Int’l. (9th Cir. 2005).

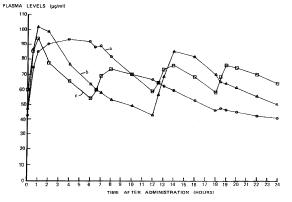

Arizona Cartridge Remanufacturers Assn. v. Lexmark Int’l. (9th Cir. 2005).  Andrx Pharma v. Elan (11th Cir. 2005)

Andrx Pharma v. Elan (11th Cir. 2005)  Illinois Tool Works v. Independent Ink (Supreme Court 2005).

Illinois Tool Works v. Independent Ink (Supreme Court 2005).