Tag Archives: motivation to combine

Patent Examiners Should Interpret Claims In Light of Specification

Solicitor General to Opine on Landmark Obviousness Case

BPAI: No Motivation to Combine Because Neither Cited Reference Recognized Advantages Discussed in Application

Suggestion to Combine References Flows from Ordinary Knowledge of those Skilled in the Art

Inconsistency Between Views of Two PTO Examiners Found Relevant to Obviousness Determination During Litigation

Apotex filed an ANDA to begin marketing a generic version of ACULAR, an ophthalmic NSAID protected by a patent owned by Syntex. Based on the Section IV filing, Syntex filed suit against Apotex for patent infringement.

After a bench trial, the district court determined that the proposed generic infringed the claims of the ACULAR patent and that the patent was not invalid.

Regarding invalidity, the district court concluded that Syntex had overcome obviousness issues by showing that the prior art taught away from the use of the drug/surfactant for opthalmic uses and that such a use created “unexpected results.” In its decision, district court noted that because the prior art at issue had been before the examiner during prosecution, the burden of proving the challenged claims obvious “is particularly high” — and that Apotex had failed to meet this heightened burden.

On appeal, the CAFC reversed — finding “clear error by the district court in several of the grounds that led it to conclude that the invention claimed by the claims in suit would not have been obvious.”

Of the several grounds for reversal, the issues of examiner discrepancy, expert testimony, and commercial success may be the most interesting:

Examiner Discrepancies:

Two different PTO examiners worked on various portions of the asserted application and its parent applications and had seemingly inconsistent views regarding patentability of the application. The CAFC found this relevant to the obviousness determination.

This statement contradicted the express finding of the initial PTO examiner that Syntex’s earlier data failed to show unexpected results. Whether the second examiner was aware of the earlier rejection of Syntex’s claims is unknown. But the relevance of the inconsistency between the views of two examiners is not insignificant.

Although we conclude . . . that Syntex did not commit inequitable conduct . . . we think the unvarnished view of the prosecution history shows some weakness in the conclusion that the patentee established unexpected results for the claimed surfactant.

Expert Testimony:

The Appellate Panel found that the district court erred by failing to examine Apotex’s expert testimony on the question of motivation to combine and unexpected results.

Commercial Success:

The district court relied heavily on the commercial success of ACULAR in its nonobviousness decision. However, the CAFC requested that the lower court revisit this issue in light of the recent case of Merck v. Teva.

In Merck, the court found that commercial success of an FDA restricted product “has minimal probative value on the issue of obviousness. . . . Financial success is not significantly probative . . . because others were legally barred from commercially testing the [] ideas.”

Concurrence:

In a concurring opinion, Judge Prost disagreed with a portion of the majority opinion that made note of “inconsistency between the views of two examiners” who examined the asserted application and a parent application.

In general, I fail to see how the conduct of a patent applicant is relevant to an obviousness determination. Alleged misconduct at the PTO, in terms of either mischaracterizations or omissions, goes to the heart of an inequitable conduct inquiry but is simply irrelevant to an obviousness inquiry.

Links:

CAFC: Court Can Only Correct Prima Facie Patent Errors

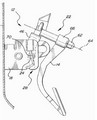

Group One owns patents on a device for curling ribbon. Hallmark manufactures pre-curled ribbon products and in 1997, was sued by Group One for infringement.

A jury found the patent valid and infringed and awarded $8.9 million in damages to Group One. However, in a post-verdict ruling, the Judge found the patents invalid.

I. Correctable Mistake on the Patent

One of Group One’s patents included a printing error by the PTO that resulted in the omission of important claim language that was added during prosecution of the application. The district court held that it lacked authority to correct the error and that only the PTO could correct the printing error. 35 U.S.C. 254.

The appellate court affirmed, finding that a district court may only correct a patent document if the error is “apparent from the face of the patent.”

II. Motivation to Combine

The patent claims require a “stripping means” that was found in several prior art references. None of the references, however, related to ribbon curling. The jury found that the references did not obviate the claims — a verdict that was overturned by the district court in a JMOL. The CAFC restored the jury verdict, finding that even the examiner’s failure to consider stripping means references could not “provide a basis for overturning the jury’s factfinding.”

Case Questions CAFC’s Obviousness Jurisprudence

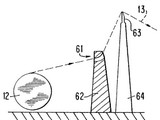

KSR International v. Teleflex (On Petition for Certiorari)

In January 2005, the CAFC decided Teleflex v. KSR — holding that when combining two or more references in an obviousness finding, there must be a suggestion or motivation to combine the teachings. This “teaching-suggestion-motivation test” has been a stalwart of Federal Circuit obviousness jurisprudence for twenty years. During that time, the Supreme Court has not heard a single obviousness case.

Now, KSR has petitioned the Supreme Court for a writ of certiorari. In its petition, the company makes a couple of interesting points that may push the High Court to accept the case:

- In Anderson’s-Black Rock (1969) and Sakraida (1976), the Supreme Court held that “a combination which only unites old elements with no change in their respective functions” is precluded from patentability under 103(a). Under the Sakraida standard, which remains law, the Teleflex patent is arguably obvious.

- With the emergence of Holmes Group, circuit splits will become more of a possibility in patent law. On this issue, the Federal Circuit has acknowledged the existence of a circuit split between itself and the Fifth Circuit. KSR points out that the split extends to other circuits as well. The other circuits have followed the Sakraisa standard while the CAFC sticks to its requirement of an explicit motivation to combine.

A consortium of five major corporations, including Microsoft, Cisco, and Hallmark have filed as amicus supporting the petition. Their brief argues that the current structured test for obviousness is too easy a hurdle for patentees and that the formalities of the test undermines courts ability to truly determine whether an invention is obvious to one skilled in the art.

In addition, Teleflex has filed its opposition to the petition — arguing that (1) obviousness is well settled law and need not be revisited; (2) the CAFC’s test is consistent with Graham; and perhaps most importantly (3) this case does not hinge on the obviousness issue.