Tag Archives: Supreme Court

Federal Circuit: State of the Court

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Patently-O Bits and Bytes No. 33: Supreme Court

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Challenge to BPAI Appointments Moves to Supreme Court

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Re-Litigating Gorham v. White: Design Patents at the Supreme Court

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Challenging Patent Validity: Microsoft Asks Supreme Court to Reduce “Clear and Convincing” Standard

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Supreme Court News: Eleventh Amendment Immunity Question

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Courts Resist Using the Term Patent Troll

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Quanta v. LG: Will the Supreme Court Clarify the Exhaustion Doctrine?

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

PTO Continuation and Claim Rules Temporarily Blocked by District Court

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Supreme Court Study: Conservatives Support IP Rights; Liberals Do Not ?

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

McFarling Petitions Supreme Court to Hear RoundUp Ready Patent Case

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Biaxin Litigation: Sandoz’ Motion for Stay Pending Appeal Denied by District Court

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Patent Exhaustion at the Supreme Court

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Supreme Court: Pharmaceutical Reverse Payments May be Considered by Supreme Court

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

In re Nuijten: Patentable Subject Matter, Textualism and the Supreme Court

[PDF Version of this Post] In re Nuijten, which is being argued to the Federal Circuit today, presents the important issue of whether a new type of artificially constructed signal may be patented. The Patent and Trademark Office opposes patentability on the grounds that, as a matter of textual interpretation, signals do not fall within any one of the four categories of patentable subject matter - "process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter" - identified in section 101 of the Patent Act. PTO Br. at 12 (quoting 35 U.S.C. § 101). Though Nuijten raises important issues concerning the scope of patentable subject matter under U.S. law (and that's reason enough for most patent practitioners and scholars to care about its outcome), the case is also about much more. It is about the fundamental approach to interpreting the Patent Act and the effect of the Supreme Court's recent interest in patent cases. To appreciate those larger issues, we must begin with a basic understanding of the facts at issue.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

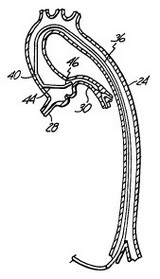

Voda v. Cordis: Plaintiff May Not Assert Foreign Patents in US Courts

Jan Voda, an Oklahoma medical doctor sued Cordis for infringement of his patent on an interventional cardiology catheter. Voda had obtained patents both in the US and abroad. Not wanting to waste time and money on multiple suits, Voda asked the US court to also determine his claims of foreign infringement based on his patents in the UK, Canada, France, and Germany. The US court agreed, but Cordis appealed — arguing that the district court improperly extended its jurisdiction.

In a 2–1 decision, the Federal Circuit (Gajarsa) has held that the district court cannot exercise supplemental jurisdiction over Voda’s foreign patent claims. Judge Newman dissents.

Supplemental Jurisdiction: Federal courts are designed to hear federal law. But, every day they exercise their power to decide issues that arise under the law of other jurisdictions. Usually the other jurisdictions are US states and municipalities. But, the courts are also regular interpreters of non-US law as well. Non-Federal questions arise based on either “diversity jurisdiction” or “supplemental jurisdiction.” Supplemental jurisdiction is spelled-out in 28 USC 1367:

[after establishing] original jurisdiction, the district courts shall have supplemental jurisdiction over all other claims that are so related to claims in the action within such original jurisdiction that they form part of the same case or controversy under Article III of the United States Constitution.

In many cases, supplemental jurisdiction has been found to extend to include foreign law claims. However, the “so related” portion of the statute has been interpreted to require that the supplemental claims arise from a “common nucleus of operative fact” and that the claims would “ordinarily be expected to [all be tried] in one judicial proceeding.” Here, the CAFC did not determine whether supplemental jurisdiction exists because it found that the district court had abused its discretion (see below).

Discretion and Comity: Even if jurisdiction exists, its exercise is “within the discretion of the district court.” The CAFC found that the district court abused its discretion by ignoring the Paris Convention, TRIPS and concepts of comity.

Like the Paris Convention, nothing in the PCT or the Agreement on TRIPS contemplates or allows one jurisdiction to adjudicate patents of another. . . . Based on the international treaties that the United States has joined and ratified as the "supreme law of the land," a district court’s exercise of supplemental jurisdiction could undermine the obligations of the United States under such treaties, which therefore constitute an exceptional circumstance to decline jurisdiction under § 1367(c)(4). Accordingly, we must scrutinize such an exercise with caution. . . .

The territorial limits of the rights granted by patents are similar to those conferred by land grants. A patent right is limited by the metes and bounds of the jurisdictional territory that granted the right to exclude. Therefore, a patent right to exclude only arises from the legal right granted and recognized by the sovereign within whose territory the right is located. It would be incongruent to allow the sovereign power of one to be infringed or limited by another sovereign’s extension of its jurisdiction. Therefore, while our Patent Act declares that "patents shall have the attributes of personal property," 35 U.S.C. § 261, and not real property, the local action doctrine constitutes an informative doctrine counseling us that exercising supplemental jurisdiction over Voda’s foreign patent claims could prejudice the rights of the foreign governments.

. . . Because the purpose underlying comity is not furthered and potentially hindered in this case, adjudication of Voda’s foreign patent infringement claims should be left to the sovereigns that create the property rights in the first instance.

Judicial Economy: While the CAFC agreed with voda that “consolidated multinational patent adjudication could be more efficient,” the court worried that it would also cause additional problems of confusion and difficulty understanding and enforcing foreign actions.

Changing Circumstances: Finally, the court left the door open if “circumstances change.”

In addition, we emphasize that because the exercise of supplemental jurisdiction under § 1367(c) is an area of discretion, the district courts should examine these reasons along with others that are relevant in every case, especially if circumstances change, such as if the United States were to enter into a new international patent treaty or if events during litigation alter a district court’s conclusions regarding comity, judicial economy, convenience, or fairness.

Vacated and Remanded

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Microsoft v. AT&T: Transnational Patent Law At The Supreme Court

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Appeals Court orders Eolas v. Microsoft Patent Case to be Reassigned

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

eBay Casualty: E.D. Texas Court Denies Injunctive Relief to Halt Microsoft’s Infringing Activities

z4 Technologies, Inc. v. Microsoft (E.D.Texas 2006)

z4 Tech appears to be the first post-eBay decision denying a permanent injunction after a patent has been valid and infringed. Here, the jury found that the patents were willfully infringed by Microsoft and that there was insufficient evidence to find the patents invalid. z4 then asked the Court to enjoin Microsoft from making, using, or selling its infringing product (Windows XP).

The Court followed the “traditional four-factor test used by courts of equity.” to determine whether to issue an injunction:

I. Irreparable Injury to Patentee: The patentee argued that infringement of a patent created a rebuttable presumption of irreparable harm to the patentee. The district court dismissed this “creative” argument as lacking precedential foundation:

z4's arguments for the application of a presumption of irreparable harm are creative, but z4 cannot cite to any Supreme Court or Federal Circuit case that requires the application of a rebuttable presumption of irreparable harm with regard to a permanent injunction.

In fact, the court cited the Supreme Court case of Amoco Production for the proposition that a presumption of irreparable harm in the context of an injunction is “contrary to traditional equitable principles.”

Because z4 does not create any products, the Court found that z4 the first factor weighed in favor of the willful infringer, Microsoft.

In the absence of a permanent injunction against Microsoft, z4 will not suffer lost profits, the loss of brand name recognition or the loss of market share because of Microsoft’s continued sale of the infringing products. These are the type of injuries that are often incalculable and irreparable. The only entity z4 is possibly prevented from marketing, selling or licensing its technology to absent an injunction is Microsoft. As . . . z4 can be compensated for any harm it suffers in the way of future infringement at the hands of Microsoft by calculating a reasonable royalty for Microsoft’s continued use of the product activation technology. Accordingly, z4 has not demonstrated that it will suffer irreparable harm absent a permanent injunction.

II. Remedies Available at Law (Is Money Sufficient?): Here, the court cited Kennedy’s concurring opinion from eBay:

Justice Kennedy specifically mentioned the situation where a “patented invention is but a small component of the product the companies seek to produce” and states that in such a situation, “legal damages may well be sufficient to compensate for the infringement and an injunction may not serve the public interest.” . . .

Here, product activation is a very small component of the Microsoft Windows and Office software products that the jury found to infringe z4's patents. The infringing product activation component of the software is in no way related to the core functionality for which the software is purchased by consumers. Accordingly, Justice Kennedy’s comments support the conclusion that monetary damages would be sufficient to compensate z4 for any future infringement by Microsoft.

In addition, Microsoft has promised that its new version of Windows (2007) will phase out all the infringing components. Thus, any ongoing royalty would only last for a couple of years. “For the reasons stated above, z4 has not demonstrated that monetary damages are insufficient to compensate it for any future infringement by Microsoft.”

III. Balance of Hardships: Microsoft argued that it would be really hard to redesign even a small component of Microsoft office. From what I have heard about the complicated code noodle, that assertion must be true. Thus, the court found that the balance of the hardships weigh in favor of Microsoft.

IV. Public Interest: Microsoft office is really popular, and “it is likely that any minor disruption to the distribution of the products in question could occur and would have an effect on the public due to the public’s undisputed and enormous reliance on these products. . . . Although these negative effects are somewhat speculative, such potential negative effects on the public weigh, even if only slightly, against granting an injunction.”

Commentary: As I predicted earlier, one way to avoid an injunction is to be a very successful infringer. I would have suspected that Microsoft’s willfulness would have weighed in z4’s favor, but the court did not even mention willfulness in its analysis of the equitable relief factors.

In a forthcoming paper code-named Injunction Denied, I address the issue of injunctive and monetary relief in patent cases. In particular, I focus on the situation where equities favor the defendant, and ask the question what monetary remedy a court should then impose? My answer may surprise you. . .

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.