by Dennis Crouch

Despite California’s policies limiting non-compete agreements, the law still lays an implicit powerful fiduciary duty on employees. The (proposed) Restatement (Third) of Employment Law indicates that competition by current managerial employees violates the duty of loyalty but that a manager has the right to “prepare to compete.” One question that arises from the facts of the case below is whether an employee who obtains patents on-the-side in preparation to compete is somehow violating his fiduciary duty.

Robert Kulakowski v. Verimatrix, Inc. (Cal. Appellate Ct. 2014) Decision Text

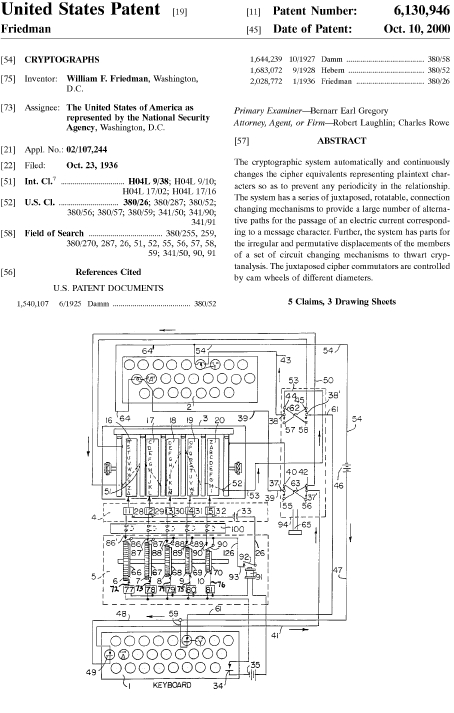

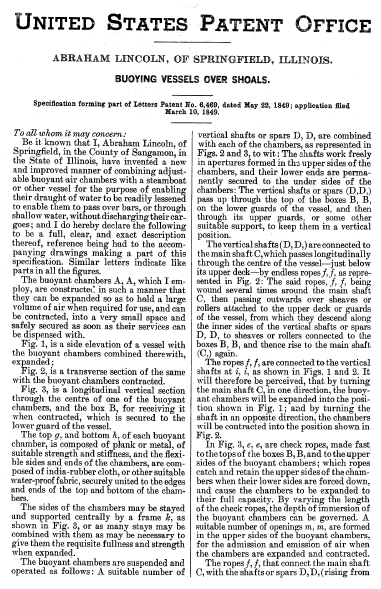

Back in 2000, Kulakowski helped to found Verimatrix – acting as the company’s chief technology officer (CTO) and directing product development. The company makes video encryption security systems known as Conditional Access Systems or CAS.

In his last year with the company, Kulakowski began working on side projects. As part of that process, he was able to modify his IP and non-compete agreement with Verimatrix to clarify that he did not need to disclose to Verimatrix any inventions “conceived, reduced to practiced or developed by [Kulakowski] in [his] own time; without using the Company’s equipment, facilities, or trade secret information; and which is not the result of work performed by me for the Company.” Meanwhile, Kulakowski founded a new company (Secure TV) in May 2010 also operating in the CAS market but then expressly denied to his Verimatrix boss that the new company was in the CAS market. In September 2010 Kulakowski left Verimatrix and then filed a patent application known as Dynamic Obfuscation Processing.

This case arose when Kulakowski filed a declaratory judgment action in California state court asking for a ruling that Verimatrix held no right to title or interest in the new patents.

Following a bench trial, the lower court ruled in favor of Verimatrix — holding (1) that declaratory relief is not called for at this time because the patent applications are pending and may still be amended; and, alternatively, (2) that Kulakowski’s claim for equitable relief should fail because of his unclean hands based upon his breach of fiduciary and contractual duties owed to the company while he was still employed.

Seeing some of the logic of the lower court, Kulakowski accepted that the DJ action was not ripe appeal. However, he appealed the unclean portion of the opinion — arguing particularly that the lower court’s DJ decision was effectively jurisdictional with the consequence that the court lacked jurisdiction to then decide the unclean hands defense. That conclusion follows from the notion that a court who lacks subject matter jurisdiction has no power to make any findings on the merits of a proceeding.

On appeal, the California appellate court rejected Kulakowski’s arguments and affirmed the lower court ruling. Here, the appellate court found that the lower court’s first ruling on the DJ action for practical reasons, not for jurisdictional reasons.

If a court decides for practical reasons it is not necessary or proper to grant declaratory relief, there is no jurisdictional prohibition to the court making alternate findings based on the evidence before it.

The case may be revived once the patents issue or a more concrete dispute arises at that point the court will need to address whether the unclean hands decision here has a preclusive effect. The appellate court expressly refused to “offer any opinion on the extent to which the court’s alternative findings are binding on either party under res judicata or collateral estoppel doctrines.”

Federal Circuit Judge Randall Rader has been sitting by designation as a district court judge in the Northern District of New York. His case is an epic patent battle between Cornell University and Hewlett-Packard (HP), and the jury trial recently concluded with an $184 million calculated as 0.8% of HP’s $23 Billion in sales.

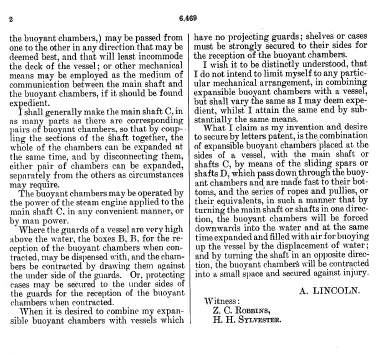

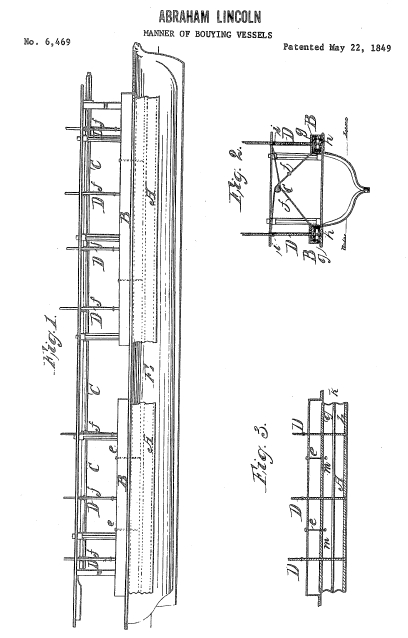

Federal Circuit Judge Randall Rader has been sitting by designation as a district court judge in the Northern District of New York. His case is an epic patent battle between Cornell University and Hewlett-Packard (HP), and the jury trial recently concluded with an $184 million calculated as 0.8% of HP’s $23 Billion in sales.  Although I understand the reality that most patent prosecution is handled on behalf of corporate assignees, I still hold a special place in my heart for the maverick American inventor. Some might understand the slight pangs I felt when reading the inventorship section of the

Although I understand the reality that most patent prosecution is handled on behalf of corporate assignees, I still hold a special place in my heart for the maverick American inventor. Some might understand the slight pangs I felt when reading the inventorship section of the  Boston Scientific SciMed v. Medtronic Vascular (Fed. Cir. 2007).

Boston Scientific SciMed v. Medtronic Vascular (Fed. Cir. 2007).

I hope that everyone has a happy Thanksgiving. Even if you are not in the U.S., I suggest that you take the day off to celebrate. Although I love turkey, I hope that you don’t deep-fry yours.

I hope that everyone has a happy Thanksgiving. Even if you are not in the U.S., I suggest that you take the day off to celebrate. Although I love turkey, I hope that you don’t deep-fry yours.

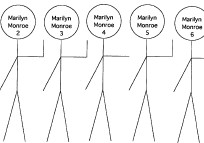

If you were to see a singular Marilyn Monroe walking down the street, you probably would notice. If, however, you were to see 88 Identical Marilyn Monroes’s single filing fashionably in parade-dress parade, you would likely stop whatever you were doing and stare in exasperated amazement wondering all the while what in the world was going on. . . . By extension then, a Volkswagen beetle limousine with 88 humps, does not look the same, does not function the same, and is, in fact, not the same, as a Volkswagen beetle with 1 hump because they do not share identical Automotive DNA.

If you were to see a singular Marilyn Monroe walking down the street, you probably would notice. If, however, you were to see 88 Identical Marilyn Monroes’s single filing fashionably in parade-dress parade, you would likely stop whatever you were doing and stare in exasperated amazement wondering all the while what in the world was going on. . . . By extension then, a Volkswagen beetle limousine with 88 humps, does not look the same, does not function the same, and is, in fact, not the same, as a Volkswagen beetle with 1 hump because they do not share identical Automotive DNA.