All posts by Dennis Crouch

Patentees Can Still Win in the US

Two Discovery Disputes

Distributing Cases in W.D.Tex.

Arthrex back at SCT: Does Director Review Require a Director?

Prior Narrow Definition Does Not (Necessarily) Limit Claim Scope in Family Member

Schedule-A Example

Guest Post: We need to talk about the NDIL’s Schedule-A cases

By Sarah Burstein, Professor of Law at Suffolk University Law School

- ABC Corp. I v. Partnership & Unincorporated Associations Identified on Schedule “A,” No. 21-2150 (Fed. Cir. 2022);

- ABC Corp. I v. Partnership & Unincorporated Associations Identified on Schedule “A,” No. 22-1071 (Fed. Cir. 2022)

On October 28, the Federal Circuit released two decisions stemming from a single case in the Northern District of Illinois. These appear to be the first—and certainly the first precedential—Federal Circuit cases dealing with the merits of one of the numerous “Schedule A” design patent cases that have been filed in recent years in the NDIL.

And when I say “numerous”: A search of Lexis CourtLink for NDIL cases with “Schedule A” in a party name results in a list of 2,669 cases filed since 2011.

In these cases, the plaintiffs name the defendants (and sometimes themselves) only in sealed “Schedules A.” Sometimes they don’t even file the patent number publicly. See, e.g., this case.

These plaintiffs assert that this secrecy is necessary to defeat nefarious Chinese “counterfeiters” who are monitoring U.S. PACER dockets. The use of this “counterfeiting” rhetoric is troubling in and of itself (for reasons including the ones I discussed in this previous Patently-O post) but these cases raise a number of additional concerns.

Professor Lorianne Updike Toler outlined some of these concerns in her motion to file an amicus brief in a different Schedule A case. That motion was denied because the judge (a different one from the one involved in the cases that are the focus of this post) felt that allowing Professor Toler “to present new arguments (no matter how meritorious or persuasive) on behalf of absent Defendants would thus pay insufficient heed to the principle of party presentation.”

One issue Professor Toler raised in her motion was the issue of fair notice. And, indeed, in ABC Case No. 21-2150, the Federal Circuit reversed a 2020 preliminary injunction (and a related order) because the judge issued preliminary injunctions against parties who had not yet been served with process and who were not given proper notice pursuant to Federal Rule of Procedure 65.

Since I first noticed the uptick in these cases a few years ago, I’ve had my own concerns about these cases, largely focused on the merits of these claims. These complaints often don’t include pictures of the infringing products in their publicly-filed pleadings, so an outside observer has no way to tell whether the claims have merit or not.

The Federal Circuit’s decision in ABC Case No. 22-1071 does nothing to assuage these concerns. In that decision, the Federal Circuit reversed a 2021 preliminary injunction in the same case, finding the court improperly analyzed the issue of design patent infringement.

It is clear, from reading the decision, that the design patent infringement claims lacked merit. The plaintiff’s infringement expert (and one might seriously question whether a designer’s option satisfies the requirements of Federal Rule of Evidence 702 when the standard for infringement relies on the perspective of the hypothetical ordinary observer, not on the perspective of a designer of ordinary skill) seemed to be a victim of what I’ve referred to as “the concept fallacy” in design patent litigation—i.e., the erroneous view that design patent protect design concepts, as opposed to the actual shapes or surface designs claimed.

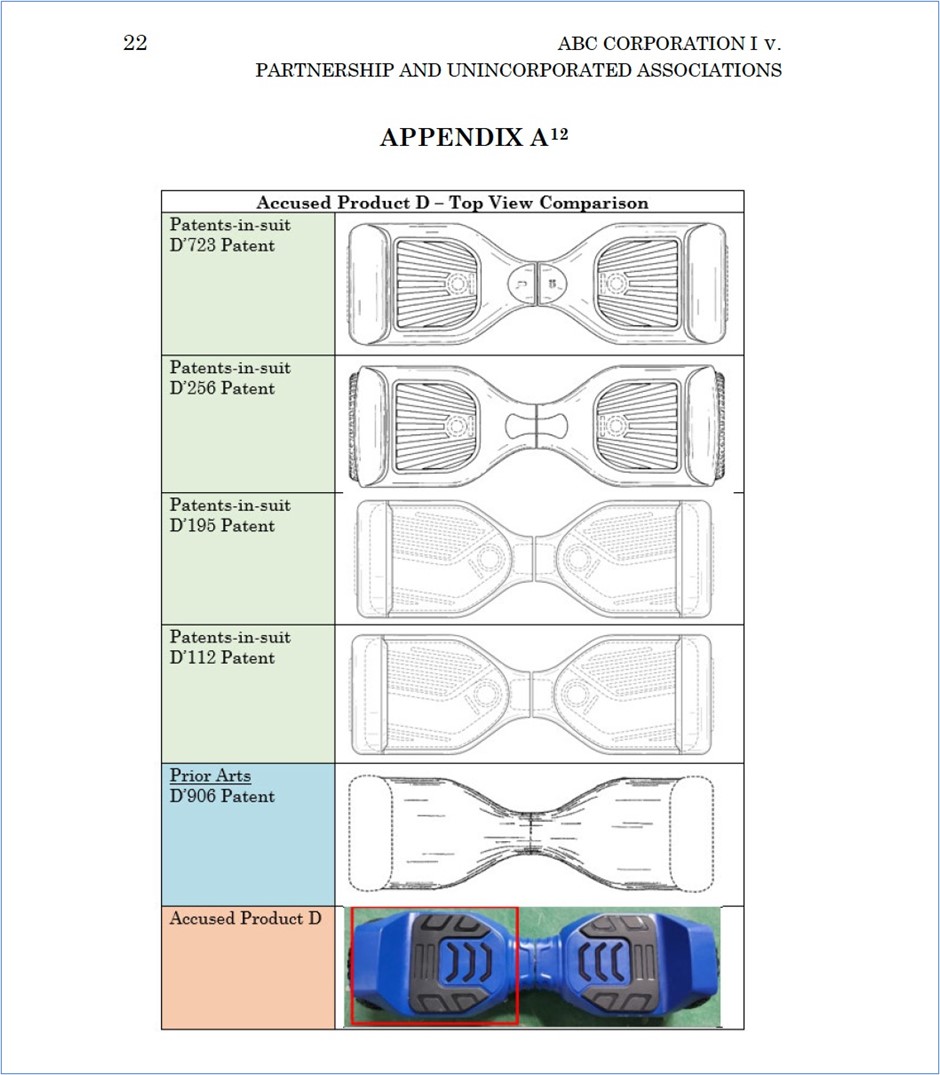

Specifically, the plaintiff’s expert appeared to believe that the patents-in-suit covered the concept of a hoverboard with an “hourglass shape.” They do not.

Additionally, the expert appears to have relied on a theory—never adopted by, and in fact, specifically rejected by the Federal Circuit—that posits that a design patent may be entitled to a broader scope if it is “far from” the prior art. That’s not how design patent infringement works. As I explained here: “The use of the prior art in the design patent infringement analysis is a one-way ratchet—it can be used to narrow the presumptive scope of a claim but cannot be used to broaden it.” (For more on how the test for design patent infringement actually does work, see this short essay.)

These are serious problems, especially to the extent that the district court thought that “[r]esolving this expert dispute will likely require a trial.”

* * *

The panel’s discussion of the infringement standard on the merits also merits further discussion. In its decision on the 2021 injunction, the Federal Circuit correctly notes that the district court erred in concluding that a putative “clash of experts” meant that the plaintiffs had discharged their burden to show a likelihood of success on the merits. And the panel was correct that, overall, the plaintiffs failed to prove they were likely to succeed on the merits

But other parts of the Federal Circuit panel’s analysis are problematic.

For example, in a footnote, the panel suggests that “substantial similarity” means the same thing in design patent that it does in copyright. The panel suggests that the duplication of a “dominant feature” of a design patent might sometimes be sufficient to constitute design patent infringement:

In other words, where a dominant feature of the patented design and the accused products—here the hourglass shape—appears in the prior art, the focus of the infringement substantial similarity analysis in most cases will be on other features of the design. The shared dominant feature from the prior art will be no more than a background feature of the design, necessary for a finding of substantial similarity but insufficient by itself to support a finding of substantial similarity.

Op. at 13-14. This suggestion misapprehends the standard set forth by the en banc Federal Circuit in Egyptian Goddess.

As the en banc court made clear in Egyptian Goddess, design patent infringement requires evaluation of the design as a whole. That is very different from the way that copyright infringement is evaluated today.

In Egyptian Goddess, the en banc Federal Circuit was very clear: The prior art can be used to only to narrow the presumptive scope of the design. That is because “where there are many examples of similar prior art designs, as in a case such as Whitman Saddle, differences between the claimed and accused designs that might not be noticeable in the abstract can become significant to the hypothetical ordinary observer who is conversant with the prior art.” It is not, as the panel suggests here, due to some kind of “dominant feature” dissection analysis.

But in this case, we shouldn’t even have to get to the prior art step. The accused product shown in this decision is “plainly dissimilar” from the claimed design:

As can be seen from these images (included in the panel decision), there are numerous differences—none of them immaterial—between the shape of the claimed designs and the accused products. These are plainly dissimilar designs. The analysis should have ended at Egyptian Goddess step 1 with a finding of noninfringement.

So the result here (no injunction) is plainly correct. But the panel’s analysis muddies the Egyptian Goddess waters in unhelpful—and utterly unnecessary—ways.