Biologics Patent Enforcement: Regeneron Patents Block Biosimilar Entry for EYLEA

by Dennis Crouch

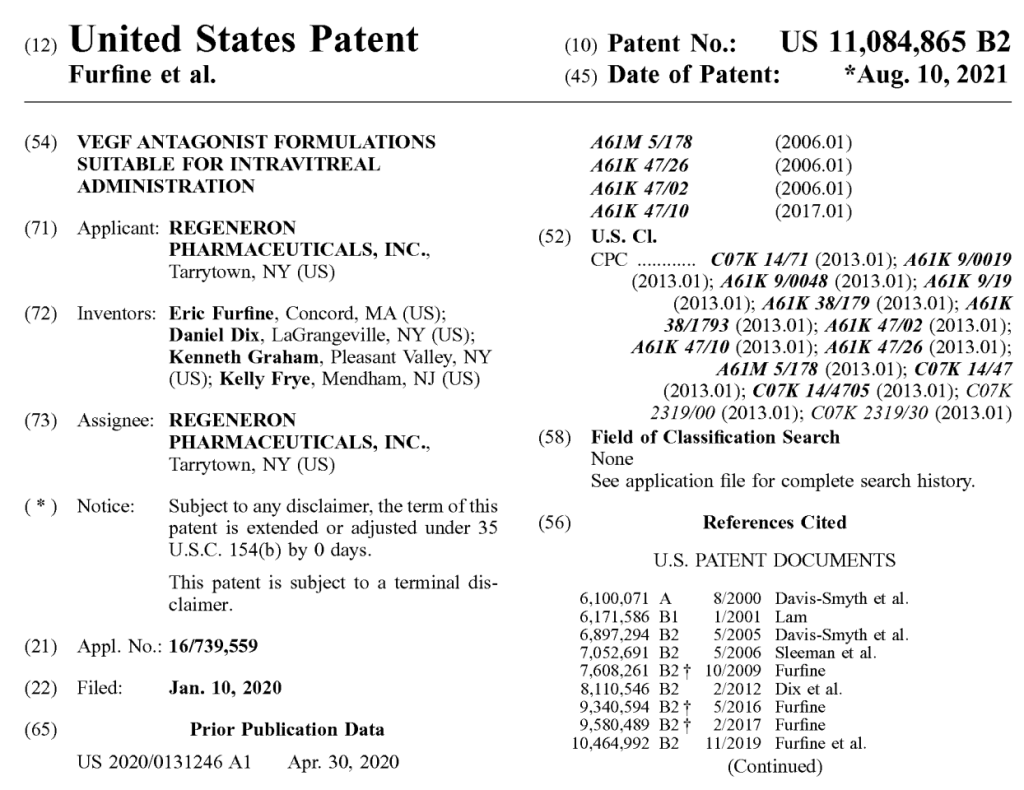

In a pair of significant decisions issued today, the Federal Circuit upheld preliminary injunctions blocking the launch of biosimilar versions of Regeneron's blockbuster drug EYLEA® (aflibercept). Regeneron Pharms., Inc. v. Mylan Pharms. Inc., No. 2024-1965 (Fed. Cir. Jan. 29, 2025) (precedential); and Regeneron Pharms., Inc. v. Mylan Pharms. Inc., No. 2024-2009 (Fed. Cir. Jan. 29, 2025) (nonprecedential). The cases pit Regeneron against foreign manufacturers, including Samsung Bioepis (SB) and Formycon AG, who had obtained FDA approval for their biosimilar products under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA). Writing for a unanimous panel, Judge Taranto focused on three key issues: (1) personal jurisdiction over foreign biosimilar manufacturers; (2) obviousness-type double patenting in the biologics context; and (3) standards for preliminary injunctive relief. The decisions effectively maintain Regeneron's market exclusivity for EYLEA®, which generates approximately $6 billion in annual sales and serves as a primary treatment for several serious eye conditions including wet age-related macular degeneration. U.S. Patent No. 11,084,865.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.