Is Google Simply Asking for More Efficient Infringement?

Discovery, Injury, and Diligence: Reconciling Subjective and Objective Copyright Limitations Standards Post-Warner Chappell

USPTO’s Remote Work Program Faces Potential Rapid Dismantling Under New Federal Guidelines

by Dennis Crouch

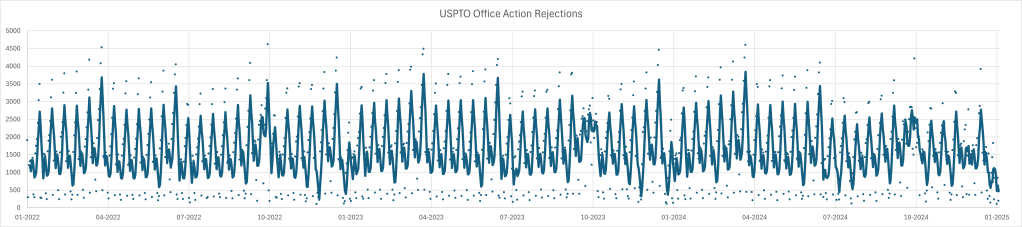

Last week, I wrote about the twin challenges facing the USPTO: a return-to-office mandate and a hiring freeze that could significantly impact patent operations. Today’s joint memorandum from OMB and OPM provides a rapid timeline for implementing these changes, with agencies required to submit detailed implementation plans by February 7th, 2025. [OMB OPM Come Home Memo].

The USPTO must develop a comprehensive plan addressing not just space and staffing, but also the “risks, barriers, and resource constraints” that could prevent expeditious return to in-person work. While patent examiners await official word from agency leadership about their specific situations, the clock is ticking on what could be the most significant operational change at the USPTO in decades.

As someone who practiced 20 years ago — at a time when USPTO examiner morale was low and the agency had difficulty recruiting quality candidates — I recognize that things are so much better today. (Do you agree?). For those of us outside the USPTO, now is the time to voice support both for the examiner community and uninterrupted USPTO operations — especially if you can provide Dir. Stewart with evidence that will aid efforts to water-down the negative effect of these orders.

Fraud on the Court: Finality and the Ghost of Hazel-Atlas

View your member account page here: https://patentlyo.com/member_account.

The Reverse Doctrine of Equivalents: An “Anachronistic Exception” Lives Another Day

Detailed Return-to-Office Implementation Guidance: Potentially Major Disruption for USPTO Operations

Federal Circuit (Again) Upholds Ravgen’s Fetal DNA cffDNA Patent

Rocky Start for the USPTO under President Trump and Director Stewart

by Dennis Crouch

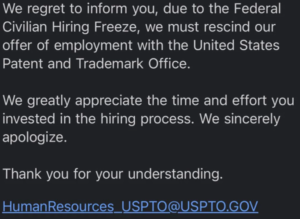

It is tough that one of the very first acts of new USPTO Director Coke Morgan Stewart’s was to cancel hiring for the agency. Two weeks ago I saw a notice that the USPTO expected to hire over 800 new examiners during 2025 in an attempt to address the ever growing backlog of unexamined patent applications. But, today the agency rescinded offers already given and cancelled its job ads. Although unclear, examiners still in their first year probationary period may also be let go. What we have here is the patent office being caught up in the larger political theatre with real world consequences — directly for those individuals losing promised employment and more generally for the intellectual property system as a whole.

This is the first time I have ever searched USAJobs and found nothing for the USPTO.

1. A system comprising:

a memory that stores instructions; and

one or more processors configured by the instructions to perform operations comprising:

causing presentation, at a first user device associated with a first user of an interaction system, of a prompt selection interface of an interaction application provided by the interaction system, the interaction application enabling the first user to obtain automatically generated images and to interact with at least a second user of the interaction system;

receiving, from the first user device and via the prompt selection interface of the interaction application, an image generation request comprising a text prompt;

responsive to receiving the image generation request via the prompt selection interface of the interaction application, generating, via an automated text-to-image generator associated with the interaction system and based on the text prompt, an image;

causing presentation, at the first user device, of the image in an image selection interface of the interaction application;

receiving, from the first user device and via the image selection interface of the interaction application, an indication of user input to select the image; and responsive to receiving the indication of the user input to select, via the image selection interface of the interaction application, the image generated via the automated text-to-image generator: modifying, using the selected image generated via the automated text-to-image generator, a user image that is associated with the first user within the interaction system, and enabling the second user of the interaction system to be presented with the modified user image via the interaction application.

Heartbeat of the USPTO

Trading Technologies Files Supreme Court Petition on Patent Eligibility, Rule 60(b)(3), and Federal Circuit Procedural Issues

USPTO Faces Twin Challenges: Return-to-Office Mandate and Hiring Freeze Could Significantly Impact Patent Operations

Welcome USPTO Director Coke Morgan Stewart

Fast Track: Chinese Origin Patents Racing Through USPTO via PPH

Priority by Two Days: TTAB Grants Cancellation in Domain Name Dispute Turned Trademark Battle

by Dennis Crouch

As someone quite familiar with the subject matter, I was looking forward to writing about the trademark battle of Nerdio, Inc. v. NerdIO Limited. The appeal was recently dismissed based upon a joint stipulation, but I still wanted to dig into the TTAB file for a few nuggets. Nerdio, Inc. v. NerdIO Limited, Cancellation No. 92075281 (TTAB May 14, 2024). As the headline suggests, the mark was cancelled here based upon two days of prior use by the opposition.

Petitioner Nerdio, Inc. provides cloud-based IT services to small and mid-sized businesses under the NERDIO mark and the website getnerdio.com. Respondent NerdIO Limited is owned by Honk-Kong based Edmond Chow, who purchased the nerdio.com domain name in 1999 with stated plans to eventually commercialize it for software services. In May 2016, Nerdio’s predecessor attempted to purchase the nerdio.com domain from Chow through a series of escalating offers, sending twelve separate emails between May 4-27. Chow rejected these offers with a single reply stating “The domain is not for sale.” (The dollar values of the offers is confidential). After a final purchase attempt on June 8, 2016, Chow filed an intent-to-use application for the NERDIO mark the very next day (June 9, 2016). Registration No. 6153453 issued to NerdIO Limited on September 15, 2020, for various computer software related services. Meanwhile, after failing to acquire the domain, Nerdio’s predecessor launched its services at getnerdio.com and later petitioned to cancel Chow’s registration based on its alleged prior common law rights in the NERDIO mark.

First-in-Time: Just like the old fox case from property law, trademark priority is fundamentally based on a first-in-time principle. At common law, we’re looking for the first use of a mark in commerce, but the Lanham Act provides important constructive use rights for intent-to-use (ITU) applications. Under Section 7(c) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1057(c), filing an ITU application establishes a nationwide constructive use date as of the application filing date, contingent upon eventual registration.

(c) Application to register mark considered constructive use.

Contingent on the registration of a mark on the principal register . . . the filing of the application to register such mark shall constitute constructive use of the mark, conferring a right of priority, nationwide in effect, on or in connection with the goods or services specified in the registration against . . .

This means that even though the applicant has not yet used the mark in commerce, once their mark registers, their priority rights will relate back to their application filing date. This constructive use right operates as a placeholder, effectively reserving priority from the application date against anyone who hasn’t used the mark before that date. However, if another party can prove actual use of the mark in commerce before the ITU application’s filing date, that party has superior rights. This operation is similar to the patent system where patent applications establish an inchoate right that becomes perfected upon patent issuance, trademark intent-to-use applications create a contingent priority right that becomes fixed when the mark registers. This concept also has historical parallels to the European doctrine of discovery in international law during the age of empires, where planting a flag could establish a preliminary claim to territory that would only become perfected through actual settlement and possession.

In Nerdio, Chow filed his intent-to-use in June 9, 2016 and eventually registered the trademark in the year 2000 — completing the requirement to establish the 2016 date.

Unfortunately for Chow, Nerdio Inc.’s predecessor (Adar IT) beat that date by two days via a June 7, 2016 email to its existing customers. The email informed these customers that the company had been “rebranded NERDIO.” Notice here that this email was not simply marketing, but was sent to actual customers who were already receiving IT services from the company. The TTAB found this significant because unlike other evidence of NERDIO usage (like the new website or promotional materials), this email was connected to actual services being rendered to paying customers.

In its decision, the TTAB found the email, combined with the context of ongoing service to these customers, established trademark use as of June 7 – just two days before NerdIO Limited’s June 9 intent-to-use application.

I couple of weeks earler, Nerdio Inc. had launched its getnerdio.com website – but the TTAB found that act was insufficient because it merely offered rather than rendered services. And, evidence of free trials starting June 2 failed because no trials actually began until after June 9. Similarly, social media promotion in early June showed only offers of service, not actual rendering. The TTAB cited Couture v. Playdom, Inc., 778 F.3d 1379 (Fed. Cir. 2015) for its conclusion that merely offering services is insufficient – the services must actually be rendered to constitute use in commerce.

Although Nerdio had a two day priority over Chow because of its prior use (via email to customers) – that priority does not settle the matter because common law use priority tends to be quite narrow in scope. When a party claims priority based on common law use against a registered mark, they must prove use of their mark for specific services that predate the registration’s priority date. This creates an important limitation – the prior user can only claim priority for the particular services they were actually providing before the critical date, not for related or expanded services they began offering later. While Nerdio Inc. proved it was providing certain IT services (monitoring computer systems, outsourced IT consulting, and implementing computer technologies) under the NERDIO mark two days before Chow’s filing date, the TTAB strictly limited Nerdio’s priority rights to just those three services even though though Nerdio later expanded to offer a broader range of services. Still, the Board found enough overlap to create a likelihood of confusion between Nerdio’s commercial offereings and Chow’s registration.

In the end, the TTAB granted Nerdio Inc.’s petition to cancel NerdIO Limited’s registration based on likelihood of confusion with Nerdio’s prior common law rights in the NERDIO mark. The key to this outcome was Nerdio’s ability to prove it was using the NERDIO mark for specific IT services two days before NerdIO Limited’s June 9, 2016 intent-to-use application date. The best evidence being an email to existing customers about the name change and continued provisioning of services to those customers.

= = =

K&L Gates LLP represented Nerdio Inc. with a team led by Alexis Crawford Douglas. Ice Miller LLP defended NerdIO Limited with Jacqueline Lesser leading the representation.

Stays of District Court Litigation Pending Appeal of IPR Decisions

The Extraterritorial Reach of Trade Secret Law

Federal Circuit’s Filing Requirements: A Trap for Even the Experts

What are your thoughts on the TikTok Ban

Take my LinkedIn Poll: