Quality patents depend upon our ability to find and examine prior art regardless of its form. Most prior art cited by the USPTO arrives in the form of patent-related references — most notably, issued U.S. patents, published patent applications, and foreign patent documents. We know, for instance, from Columbia Professor Bhaven Sampat that about 90% of cited non-patent prior-art references are provided by the applicant, and that only 10% are examiner references. Link.

Quality patents depend upon our ability to find and examine prior art regardless of its form. Most prior art cited by the USPTO arrives in the form of patent-related references — most notably, issued U.S. patents, published patent applications, and foreign patent documents. We know, for instance, from Columbia Professor Bhaven Sampat that about 90% of cited non-patent prior-art references are provided by the applicant, and that only 10% are examiner references. Link.

In some technologies where patenting has a long and extensive tradition, the lack of non-patent prior art is not a serious problem. In other areas such as software and biotechnology, non-patent references harbor most of the important prior art.

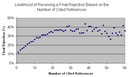

Results: My new study of 100,000 recently issued patents reveals that patent that cited non-patent literature are significantly more likely to receive rejections from the PTO. Specifically, patents citing at least one non-patent reference have a 39% greater chance of receiving a final rejection when compared with patents that issued without citing any non-patent references. Regarding non-final rejections, citing non-patent prior art increased the likelihood of receiving a rejection by 9%.