by Dennis Crouch

One ongoing debate at the PTAB has been the role of Applicant Admitted Prior Art (AAPA) in inter pates review proceedings. AAPA refers to statements made by the patentee that admit that certain subject matter is part of the prior art. These statements are typically found in the background section and might include language like:

- “It is well known that …”

- “Conventional systems use …”

- “Prior work includes …”

- “As described in [reference], it is known that …”

Examiners rely heavily on AAPA, but IPR proceedings are limited to anticipation and obviousness grounds "and only on the basis of prior art consisting of patents or printed publications." In Qualcomm Inc. v. Apple Inc., 24 F.4th 1367 (Fed. Cir. 2022) ("Qualcomm I"), the Federal Circuit sided with the patentee (Qualcomm), holding that AAPA contained within the challenged patent does itself constitute such prior art. Still, the obviousness determination looks at evidence beyond the prior art, such as the level of skill in the art, and motivation to combine references. And, the court held that AAPA could be used to prove those facts. The court noted particularly that a petitioner may properly rely on AAPA "as evidence of the background knowledge possessed by a person of ordinary skill in the art" for purposes such as "furnishing a motivation to combine" or "supplying a missing claim limitation" as part of the obviousness analysis. But see Arendi v. Apple (Fed. Cir. 2016).

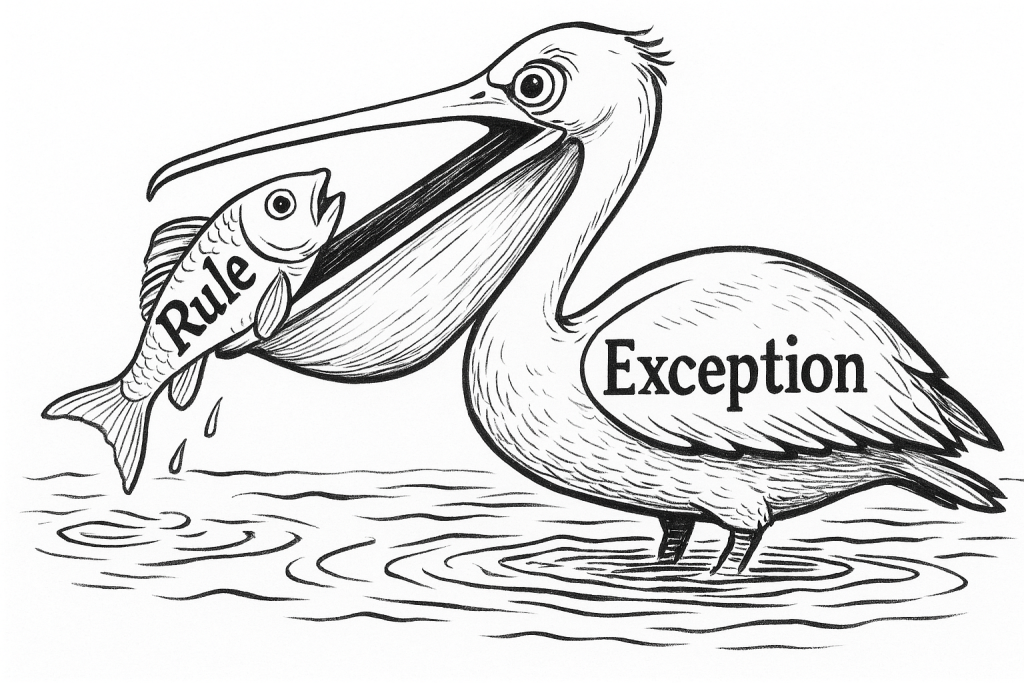

Following Qualcomm I, the USPTO issued updated guidance in on the treatment of AAPA in IPRs. Director Katherine Vidal's new guidance explicitly acknowledged the Federal Circuit's ruling that "under § 311, 'patents or printed publications' that form the 'basis' of a ground for inter partes review must themselves be prior art to the challenged patent" and not the challenged patent itself or any admissions therein. The guidance clarified that it is "impermissible for a petition to challenge a patent relying on solely AAPA without also relying on a prior art patent or printed publication."

But, the updated USPTO guidance established what would later be termed an "in combination" rule, providing that "[i]f an IPR petition relies on admissions in combination with reliance on one or more prior art patents or printed publications, those admissions do not form 'the basis' of the ground and must be considered by the Board in its patentability analysis." The guidance identified several permissible uses of AAPA in IPR proceedings, including: "(1) supply[ing] missing claim limitations that were generally known in the art prior to the invention...or the effective filing date of the claimed invention; (2) support[ing] a motivation to combine particular disclosures; or (3) demonstrat[ing] the knowledge of the ordinarily-skilled artisan at the time of the invention...for any other purpose related to patentability."

Back to Qualcomm: On remand, the PTAB applied the USPTO's "in combination" rule to conclude that Ground 2 of Apple's IPR petition complied with § 311(b). The Board determined that since Apple's challenge relied on AAPA "in combination with" prior art patents (Majcherczak and Matthews), the AAPA did not form "the basis" of the ground in violation of § 311(b). The Board rejected Qualcomm's argument that Apple had expressly included AAPA as part of the "Basis" of Ground 2 in its petition tables, concluding that these statements merely described how the grounds included both AAPA and prior art patents used "in combination."

On appeal, the Federal Circuit has once again reversed. Qualcomm Incorporated v. Apple Inc., Nos. 2023-1208, 2023-1209 (Fed. Cir. Apr. 23, 2025) (Qualcomm II). The new panel concluded that Board's interpretation contravened the plain meaning of § 311(b). Rather, the Federal Circuit held that Apple's express designation of AAPA in the "Basis" of Ground 2 was determinative, ruling that the Board erred in concluding the challenged claims were unpatentable under Ground 2 when that ground improperly included AAPA as part of its basis in violation of § 311(b).