Tag Archives: Affirmed Without Opinion

CAFC Affirms Exceptional Case Attorney Fees Based on Multiplicity of Minor Acts of Misconduct

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

CAFC Rejects Patent on Invention to Overcome the Second Law of Thermodynamics

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences (BPAI)

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Reviving Unintentionally Abandoned Patent Applications

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Warning: Do Not Rely on the Experimental Use Exception to 102(b)

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

CAFC: As a Matter of Law, Preliminary Injunction Defeated by “Casting Doubt” on Patent’s Validity

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Bilski: Full CAFC to Reexamine the Scope of Subject Matter Patentability

In re Bilski (Fed. Cir. 2008 - en Banc)

Taking sua sponte action, the Federal Circuit has ordered an en banc rehearing of the In re Bilski case – asking the following five questions:

- Whether claim 1 of the 08/833,892 patent application claims patent-eligible subject matter under 35 U.S.C. § 101?

- What standard should govern in determining whether a process is patent-eligible subject matter under section 101?

- Whether the claimed subject matter is not patent-eligible because it constitutes an abstract idea or mental process; when does a claim that contains both mental and physical steps create patent-eligible subject matter?

- Whether a method or process must result in a physical transformation of an article or be tied to a machine to be patent-eligible subject matter under section 101?

- Whether it is appropriate to reconsider State Street Bank & Trust Co. v. Signature Financial Group, Inc., 149 F.3d 1368 (Fed. Cir. 1998), and AT&T Corp. v. Excel Communications, Inc., 172 F.3d 1352 (Fed. Cir. 1999), in this case and, if so, whether those cases should be overruled in any respect?

The Patent Application and Patent Applicants: Bilski involves claims to a method of managing the risk of bad weather through commodities trading. The claims are not tied to any particular form of technology — thus, they do not require a computer or particular storage media. In some quarters, this process lacking a technological tie-in is termed a “mental method.”

Bernie Bilski apparently was the CEO and owner of a small company called WeatherWise. At least some WeatherWise patents were purchased in 2007 by the “Pittsburgh Technology Licensing Corp” According to court documents, PTL is a wholly owned subsidiary of WeatherWise holdings. (See WeatherWise v. WeatherBill).

Although we don’t have the text of the application yet, this case looks problematic because of serious obviousness problems and lack of specificity in the claims. Thus, the court will have no sympathy for Bilski — making this the perfect test case for someone wanting to strink Section 101 coverage and eliminate business method patents. Representative Claim 1 reads as follows:

1. A method for managing the consumption risk costs of a commodity sold by a commodity provider at a fixed price comprising the steps of:

(a) initiating a series of transactions between said commodity provider and consumers of said commodity wherein said consumers purchase said commodity at a fixed rate based upon historical averages, said fixed rate corresponding to a risk position of said consumer;

(b) identifying market participants for said commodity having a counter-risk position to said consumers; and

(c) initiating a series of transactions between said commodity provider and said market participants at a second fixed rate such that said series of market participant transactions balances the risk position of said series of consumer transactions.

Procedure: This cases arises out of a rejection from the Patent Board of Appeals (BPAI). In its opinion, the Board asked for assistance from the CAFC in addressing Subject Matter Patentability of non-technological method claims: “The Federal Circuit cannot address rejections that it does not see. . . . It would be helpful if the Federal Circuit would address this question directly.” BPAI Decision. Bilski then apealed directly from the BPAI to the CAFC and oral arguments were held in October 2007. Rather than issuing an opinion, the court convened and voted to rehear the case en banc.

Timing and Amicus: The parties (Bilski & PTO) have already fully briefed the case. Thus, the CAFC is only allowing one supplimental brief each to be filed simultaneously on March 6, 2008. Amicus briefs discussing the five questions are requested by the court and may be filed without specific permission. Amicus briefs will be due 30 days later and must otherwise comply with FRAP and FCR 29. (Thanks Joe: Amicus should be due April 5th, but because that falls on a Saturday, they will be due April 7). The hearing is scheduled for May 8 at 2:00 pm.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Claimed “Insert” Limitation Creates Product by Process

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Appealing the Kitchen Sink

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

The GSK Case: An Administrative Perspective

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Translogic Challenges (1) the Constitutionality of BPAI Decisions and (2) CAFC’s Retroactive Application of a PTO Proceeding to a Jury Verdict

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Claimed ‘plant cell’ must enable monocots and dicots; CAFC affirms noninfringement and invalidity of Monsanto GM corn patents

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

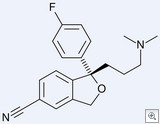

Appellate Panel Upholds Forest’s Lexapro Patent

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit today upheld Forest Labs patent on its billion dollar SSRI Lexapro (escitalopram oxalate) — rejecting IVAX’s arguments that the patent is anticipated and obvious. Based on two FDA extensions, the patent is set to expire on March 14, 2012.

This case is an important stepping stone in our new understanding of obviousness. Interestingly, in its multi-page discussion of obviousness, the appellate panel did not mention the Supreme Court’s recent landmark decision of KSR v. Teleflex.

History: Forest holds an expired patent on a racemic form of citalopram. After considerable effort, Forest’s scientists doubled the strength of the drug by isolating the (+) stereoisomer (which turned out to be the only active isomer) and patented that isomer in a “substantially pure” form. A prior art pharmacologic paper had suggested that the (-) stereoisomer would be the potent isomer, but that reference did not describe the preparation of the enantiomer.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Stay Pending Appeal: Denied for Qualcomm at ITC

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Individual Inventors: Who Will Represent You Now?

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Means-Plus-Function Element Found Indefinite Without Corresponding Structure

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

CAFC Affirms Disqualification of Defendant’s Attorneys

In re Hyundai Motor Am., 185 Fed. Appx. 940 (Fed. Cir. 2006)

Orion IP has accused dozens of companies of infringement of its business method patents ("computer-assisted sales"). At one point, Orion worked with the Orrick firm on some matters and Orrick made a pitch to handle Orion's litigation and patent strategy work. Orion demurred. Once litigation began, Orrick got back in the game by agreeing to represent several of the accused infringers directly adverse to Orion.

The Texas district court noted a conflict-of-interest and disqualified Orrick. On writ of mandamus, the CAFC affirmed -- finding no error.

The parties apparently presented diverging evidence as to the subject-matter of early meetings between Orrick and Orion and the type of documents exchanged. The CAFC noted that these were purely factual questions that the lower court "resolved in Orion's favor" without any clear error.

In order to prevail, Hyundai must clearly and indisputably show clear error in the district court's findings of fact and application of the facts to the law. Hyundai has not carried its burden. This is essentially a factual dispute, which the district court resolved in Orion's favor. The district court held a hearing, considered the competing declarations, and reviewed the pertinent documents. We do not find a basis for overturning those findings.

Disqualification affirmed.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Impact of KSR v. Teleflex on Pharmaceutical Industry

For the past 30 years, Cal has been a litigation analyst serving the investment community. He is member of the New York Bar and a graduate of Northwestern law School. www.litigationnotes.com.

=====================

By Cal Crary:

We do not believe that too much guessing is needed to see what the new patent environment will be like, since we already have the benefit of Chief Judge Michel’s March 23, 2007 decision in the Norvasc case, in which he identified the likely changes in the court’s obviousness jurisprudence. . . . A few of the principles reflected in Judge Michel’s opinion are as follows:

- routine testing to optimize a single parameter, rather than numerous parameters, is obvious;

- an approach that is obvious to try is also obvious where normal trial and error procedures will lead to the result;

- unexpected results cannot overcome an obviousness challenge unless the patentee proves what results would have been expected;

- a reasonable expectation of success does not have to be a predictable certainty but rather it can be an expectation that can be satisfied by routine experimentation; and

- motivation can be found in common knowledge, the prior art as a whole or the nature of the problem itself.

....

[T]here are certain types of patents in the pharmaceutical industry that will have to be looked at, or looked at again, in light of the Supreme Court’s opinion. We happen to believe that enantiomer patents are especially vulnerable, at least in cases in which the technology to separate them was available in the public domain at the time the separation was made. However, we do not believe that the courts will permit a massive extermination of drug industry patents or that a meat-axe approach to them will be used. Rather, we think the Supreme Court’s only demand is that common sense be injected into the determination of what a person of ordinary creative skill in the art would do. The primary examples of enantiomer patents that we regard as vulnerable include Forest Labs’ Lexapro, Bristol-Myers’ Plavix, AstraZeneca’s Nexium and Johnson & Johnson’s Levaquin. We think that all four of these drugs are especially vulnerable now, in light of the new, broader scope of obviousness. In the case of Levaquin, Mylan Labs lost at the district court level in a case that it should have won, even under the law as it existed at the time, and then it was affirmed by Judge Pauline Newman, a pro-industry Federal Circuit judge, in a non-precedential decision without opinion. In a new case, if obviousness is in the mix and if Judge Newman is avoided on appeal, then Levaquin will be a generic drug.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Sarnoff Discusses KSR v. Teleflex

By Professor Joshua Sarnoff, Assistant Director of the Glushko-Samuelson Intellectual Property Law Clinic and a Practitioner-in-Residence at the Washington College of Law, American University. Professor Sarnoff filed an amicus brief in support of Petitioner KSR.

In its unanimous decision in KSR Int’l. Co v. Teleflex Inc., No. 04-1350 (April 30, 2007), the Supreme Court expressly overruled the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit’s “teaching-suggestion-motivation” (“TSM”) test for finding a claimed invention obvious and reaffirmed the Court’s precedents (in light of the 1952 enactment of Section 103 and its holding in Graham v. John Deere Co. of Kansas City, 383 U.S. 1 (1966)) regarding the obviousness of patents “based on the combination of elements found in the prior art” where there the combination “does no more than yield predictable results.” Slip op. at 11-12. The Court’s decision has therefore called into question the validity of hundreds of thousands of claims in issued patents, and will likely lead to a dramatic change to the method by which the Patent Office, the courts, and the bar conduct their obviousness analyses.

Nevertheless, the Supreme Court’s opinion appears self-consciously narrow and provides little additional guidance for how to apply the Graham approach. The Court’s decision leaves unclear whether the party with the burden of proving obviousness must demonstrate that “there was an apparent reason to combine the known elements in the fashion claimed by the patent at issue,” or only that the claim at issue if patented would reflect an “advance[] that would occur in the ordinary course without real innovation[, which] retards progress and may, in the case of patents combining previously known elements, deprive inventions of their value or utility.” Slip op. at 14, 15. As the Court noted, “as progress beginning from higher levels of achievement is expected in the normal course, the results of ordinary innovation are not the subject of exclusive rights under the patent laws. Were it otherwise patents might stifle, rather than promote, the progress of useful arts.” Slip op. at 24. Although the Court recited the Constitutional language, it did not expressly hold that obviousness is a constitutional requirement. Further, the Court left to later case law any consideration of the extent to which the Court of Appeals’ more recent statements regarding the flexibility of its TSM test is consistent with Graham and the Supreme Court’s earlier precedents. Slip op. at 18.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.