Tag Archives: obviousness

Goodbye Rosen references, hello Jennings references?

Guest Post by Sarah Burstein, Professor of Law at Suffolk University Law School

LKQ Corp. v. GM Global Tech., 21-2348 (Fed. Cir. 2024) (en banc).

In its decision in LKQ v. GM, the en banc Federal Circuit may have raised as many questions as it answered. For now, I’d like to focus on one: What counts as a proper primary reference under LKQ? (more…)

Commenting on the USPTO’s Proposed Rule on Terminal Disclaimers

[I have substantially updated this post - correcting a couple of issues from the original and also added info from the letter from former USPTO leaders. - DC 6/1/24]

by Dennis Crouch

As I have previously discussed on Patently-O, the USPTO recently issued a notice of proposed rulemaking that could significantly impact patent practice, particularly in the realm of terminal disclaimers filed to overcome non-statutory double patenting rejections. Dennis Crouch, Major Proposed Changes to Terminal Disclaimer Practice (and You are Not Going to Like it), Patently-O (May 9, 2024). Under the proposed rule, a terminal disclaimer will only be accepted by the USPTO if it includes an agreement that the patent will be unenforceable if tied (directly or indirectly) to another patent that has any claim invalidated or canceled based on prior art (anticipation or obviousness under 35 U.S.C. 102 or 103). This proposal has generated significant debate among patent practitioners, with many expressing concerns about its potential impact on innovation and patent rights. It is a dramatic change in practice because the typical rule required by statute is that the validity of each patent claim must be separately adjudged. See 35 U.S.C. § 282(a).

The comment period is open until early July, but a number of comments have already been submitted. And I looked through them in order to get some early feedback. You can read the comments here

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

The NYIPLA Brief: Advocating for Patent Term Adjustments

by Dennis Crouch

The Federal Circuit's 2023 decision in In re Cellect, LLC, 81 F.4th 1216 (Fed. Cir. 2023) has set the stage for a potentially significant Supreme Court case on the interplay between the Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) statute, 35 U.S.C. § 154(b), and the judicially-created doctrine of obviousness-type double patenting (ODP). Cellect is now seeking certiorari, and the New York Intellectual Property Law Association (NYIPLA) has stepped in with an amicus brief supporting the petition, arguing that the case presents "questions of exceptional importance." Brief for New York Intellectual Property Law Association as Amicus Curiae Supporting Petitioner at 23, Cellect, LLC v. Vidal, No. 23-1231 (U.S. May 28, 2024).

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

USPTO Adapts to CAFC’s New Guidelines: What Design Patent Examiners Need to Know

by Dennis Crouch

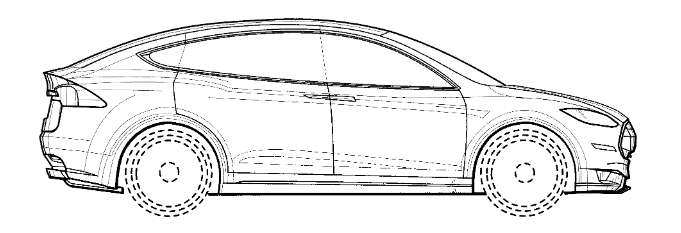

On May 22, 2024, the day after the Federal Circuit's en banc LKQ v. GM decision, the USPTO issued a memorandum to its examiners providing updated guidance and examination instructions in light of the court's overturning of the long-standing Rosen-Durling test for determining obviousness of design patents. The memo, signed by USPTO Director Kathi Vidal, aims to immediately align USPTO practices with the more flexible approach outlined by the Federal Circuit, which eliminated the rigid requirements that: (1) a primary reference be "basically the same" as the claimed design, and (2) secondary references be "so related" to the primary reference that features in one would suggest application to the other. This is a major shift in examination practice for design patents so it will be important to watch the developments to see whether the office ramps up design examination.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Speck v. Bates: Federal Circuit’s Two-Way Test for Pre-Critical Date Claims Limits Belated Interferences and Derivation Proceedings

by Dennis Crouch

Speck v. Bates, No. 23-1147 (Fed. Cir. May 23, 2024)

In likely one of the last interference proceeding appeals, the Federal Circuit has applied a "two-way test" to determine whether pre-critical date claims and post-critical date claims are "materially different" under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 135(b)(1). The court found that Bates' post-critical date claims in its U.S. Patent Application No. 14/013,591 were time-barred because they were materially different from Bates' pre-critical date claims.

Although the decision is based upon an interference proceeding, the same provision is found within the new version of 135(b) that covers

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Decoding Patent Ownership beginning with Core Principles

by Dennis Crouch

In a recent decision, the Federal Circuit vacated a district court's grant of summary judgment that an inventor, Dr. Mark Core, had automatically assigned a patent associated with his PhD thesis to his then-employer and education funder TRW. Core Optical Techs., LLC v. Nokia Corp., Nos. 23-1001 (Fed. Cir. May 21, 2024). The key issue was whether Dr. Core developed the patented invention "entirely on [his] own time" under his employment agreement. The majority opinion written by Judge Taranto and joined by Judge Dyk held the contract language was ambiguous on this point and remanded for further factual development to determine the parties' intent. Judge Mayer dissented.

Although not discussed in the court's decision, the appellant brief includes a suggestion that the Federal Circuit should "narrow or overrule" the automatic assignment law seen in FilmTec Corp. v. Allied Signal, Inc., 939 F.2d 1568 (Fed. Cir. 1991), and its progeny

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Federal Circuit Overrules Rosen-Durling Test for Design Patent Obviousness

by Dennis Crouch

In a highly anticipated en banc decision, the Federal Circuit has overruled the longstanding Rosen-Durling test for assessing obviousness of design patents. LKQ Corp. v. GM Global Tech. Operations LLC, No. 21-2348, slip op. at 15 (Fed. Cir. May 21, 2024) (en banc). The court held that the two-part test's requirements that 1) the primary reference must be "basically the same" as the claimed design, and 2) any secondary references must be "so related" to the primary reference that features from one would suggest application to the other, "impose[] limitations absent from § 103's broad and flexible standard" and are "inconsistent with Supreme Court precedent" of both KSR (2007) and Whitman Saddle (1893). Rejecting the argument that KSR did not implicate design patent obviousness, the court reasoned that 35 U.S.C. § 103 "applies to all types of patents" and the text does not "differentiate" between design and utility patents. Therefore, the same obviousness principles should govern. This decision will generally make design patents harder

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Cellect or Reject? SCOTUS Asked to Consider Fate of ODP Doctrine

by Dennis Crouch

In its new petition for certiorari in Cellect LLC v. Vidal, No. __ (U.S. May 20, 2024), Cellect argues that the Federal Circuit erred in upholding the PTAB's (PTAB) invalidation of Cellect's four patents based on the judicially-created doctrine of obviousness-type double patenting (ODP). The key issue is whether ODP can cut short the patent term extension provided by the Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) statute, 35 U.S.C. § 154(b). Meanwhile, Dir. Vidal is looking to extend the power of ODP via rulemaking. This is an important case coming at an important time.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Navigating the USPTO’s Regulatory Wave: Key Comment Deadlines for Summer 2024

by Dennis Crouch

Over the past two months, the USPTO has issued an unusually large number of public comment requests related to various proposed rules and procedure changes. This wave of RFCs includes significant proposals aimed at adjusting patent fees for fiscal year 2025, refining terminal disclaimer practices, and addressing the impact of artificial intelligence on prior art and patentability. The agency is also seeking feedback on formalizing the Director Review process following Arthrex and various changes to IPR proceedings, including discretionary review. And there's more...

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Major Proposed Changes to Terminal Disclaimer Practice (and You are Not Going to Like it)

by Dennis Crouch

The USPTO recently issued a notice of proposed rulemaking that could significantly impact patent practice, particularly in the realm of terminal disclaimers filed to overcome non-statutory double patenting rejections. Under the proposed rule, a terminal disclaimer must include an agreement that the patent will be unenforceable if it is tied directly or indirectly to another patent that has any claim invalidated or canceled based on prior art (anticipation or obviousness under 35 U.S.C. 102 or 103). The new enforceability requirement would be in addition to the existing provisions that require a terminal disclaimer to match the expiration date of the disclaimed patent to the referenced patent and promise enforcement only during common ownership.

This is a major proposal that fundamentally alters the effect of terminal disclaimers.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Patenting Informational Innovations: IOEngine Narrows the Printed Matter Doctrine

by Dennis Crouch

This may be a useful case for patent prosecutors to cite to the USPTO because it creates a strong dividing line for the printed matter doctrine -- applying the doctrine only to cases where the claims recite the communicative content of information.

IOEngine, LLC v. Ingenico Inc., 2021-1227 (Fed. Cir. 2024).

In this decision, the Federal Circuit partially reversed a PTAB invalidity finding against several IOEngine patent claims. The most interesting portion of the opinion focuses on the printed matter doctrine. Under the doctrine, certain "printed matter" is given no patentable weight because it is deemed to fall outside the scope of patentable subject matter. C R Bard Inc. v. AngioDynamics, Inc., 979 F.3d 1372 (Fed. Cir. 2020). In this case though the Federal Circuit concluded that the Board erred in giving no weight to IOEngine's claim limitations requiring "encrypted communications" and "program code."

The printed matter doctrine a unique and somewhat amorphous concept in patent law that straddles the line between patent eligibility under 35 U.S.C. § 101 and the novelty and non-obviousness requirements of §§ 102 and 103.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Cycling Towards Confusion: Is there room for iFIT Fitness Services and iFIT Safety Glasses?

by Dennis Crouch

In its initial decision, the TTAB dismissed iFIT's opposition to ERB's I-FIT FLEX registration -- finding no likelihood of confusion because the goods were in separate markets. iFIT is a major manufacturer of exercise equipment like treadmills and stationary bikes and holds several trademark registrations for IFIT marks covering fitness machines, online fitness training services and content, software, and some ancillary products like apparel. ERB Industries applied to register I-FIT FLEX for protective and safety eyewear sold at hardware stores such as Home Depot. Although the two brands are at-times sold in the same online store (Amazon.com and Walmart.com) this type of overlap was not sufficient for the TTAB. In its decision, the TTAB rejected iFIT's relatedness argument using an analogy to racecar drivers and chemists. The TTAB reasoned that while some racecar drivers and chemists may use safety glasses, that doesn't mean safety glasses are related to racecars or to chemicals like ammonia.

iFIT appealed the Federal Circuit, and most recently Federal Circuit granted

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Discerning Signal from Noise: Navigating the Flood of AI-Generated Prior Art

by Dennis Crouch

This article explores the impact of Generative AI on prior art and potential revisions to patent examination standards to address the rising tidal wave of AI-generated, often speculative, disclosures that could undermine the patent system's integrity.

In a new request for comments (RFC), the USPTO has asked the public to weigh in on these issues -- particularly focusing on the impact of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) on prior art.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

SCT: False Claims Act Actions Based Upon Fraudulently Obtained Patent Rights

by Dennis Crouch

This post walks through a new petition for writ of certiorari involving claims that Valeant Pharma defrauded the U.S. government by using fraudulently obtained patent rights prop up its drug prices. [Read the Petition]

The False Claims Act (FCA), originally enacted in 1863 to combat contractor fraud during the Civil War, imposes civil liability on anyone who "knowingly presents" a "fraudulent claim for payment" to the federal government. 31 U.S.C. § 3729(a)(1)(A). The Act allows private citizens, known as "relators," to bring qui tam actions on the government's behalf against those who have defrauded the government. If successful, relators can recover up to 30 percent of the damages. 31 U.S.C. §§ 3730(b)(4), (d)(2).

To prevent opportunistic lawsuits, however, Congress has sought to strike a "balance between encouraging private persons to root out fraud and stifling parasitic lawsuits"

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Supreme Court Declines to Hear Vanda’s Patent Obviousness Appeal

by Dennis Crouch

The Supreme Court has denied Vanda Pharmaceuticals' petition for certiorari, leaving in place a Federal Circuit decision that invalidated Vanda's patents on methods of using the sleep disorder drug Hetlioz (tasimelteon) as obvious.

Vanda had argued in its cert petition that

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

What I’m reading from academic journals

I'm always on the lookout for interesting new scholarship related to intellectual property and innovation policy. The following are a few of the articles that I've been delving into this past week:

- James Hicks, Do Patents Drive Investment in Software?, 118 NW. U. L. REV. 1277 (2024).

- Ana Santos Rutschman, From Myriad to Moderna: The Modern Pharmaceutical Company, ___ Texas A&M University Journal of Property Law ___ (2024) (forthcoming).

- John Howells, Ron D Katznelson, Freedom to Operate analysis as competitive necessity—the Selden automobile patent case revisited, Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice (2024).

- Christa Laser, Scientific Educations Among U.S. Judges, ___ American University Law Review ___ (2025) (forthcoming).

- Garreth W. McCrudden, Drugs, Deception, and Disclosure, 38 BERKELEY TECH. L.J. 1131 (2024).

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

The Use of Mandated Public Disclosures of Clinical Trials as Prior Art Against Study Sponsors

By Chris Holman

Salix Pharms., Ltd. v. Norwich Pharms. Inc., 2024 WL 1561195 (Fed. Cir. Apr. 11, 2024)

Human clinical trials play an essential role in the discovery, development, and regulatory approval of innovative drugs, and federal law mandates the public disclosure of these trials. Pharmaceutical innovators are voicing concern that these disclosures are increasingly being used as prior art to invalidate patents arising out of, or otherwise relating to, these trials, in a manner that threatens to disincentivize investment in pharmaceutical innovation. A recent Federal Circuit decision, Salix Pharms., Ltd. v. Norwich Pharms. Inc., illustrates the concern. In Salix, a divided panel upheld a district court decision to invalidate pharmaceutical method of treatment claims for obviousness based on a clinical study protocol published on the ClinicalTrials.gov. website. The case garnered amicus curiae briefs filed by several innovative pharmaceutical companies in support of the patent owner, Salix Pharmaceuticals.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Patentee’s Unclean Hands

by Dennis Crouch

The Federal Circuit's new decision in Luv'N'Care, Ltd. (LNC) v. Laurain and EZPZ, relies on the doctrine of unclean hands to deny relief to the patentee (Laurain and EZPZ), affirming the district court's judgment. The appellate panel also vacated and remanded the district court's finding that LNC failed to prove the asserted patent is unenforceable due to inequitable conduct during prosecution, as well as its grant of summary judgment one of the asserted patents was invalid as obvious. U.S. Patent No. 9,462,903. The case here involves bowls/plates attached to a mat to help avoid spills and for easy cleanup. 22-1905.OPINION.4-12-2024_2300689.

Unclean Hands: The doctrine of unclean hands is an equitable defense that bars a party from obtaining relief when they have engaged in misconduct

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Patent Term Adjustment and Obviousness-Type Double Patenting: Cellect’s Bid for Supreme Court Review

by Dennis Crouch

The Federal Circuit's August 2023 decision in In re Cellect, LLC has set-up a significant question regarding the interplay between the patent term adjustment (PTA) statute, 35 U.S.C. § 154(b), and the judicially-created doctrine of obviousness-type double patenting (OTDP). Now, Cellect is seeking Supreme Court review, recently filing a petition for an extension of time that also indicated its intent to file. Cellect's petition is now due May 20, 2024, and I expect significant support from the patent owner community.

Patentees often receive PTA due to USPTO delays that otherwise eat into the 20-year patent term. A fundamental issue in Cellect boils down to whether a patentee must forfeit their PTA term extensions to avoid an OTDP invalidity finding. This comes up in situations where a patentee has two patents that cover only slightly different inventions. Most often this is seen in family-member continuation applications, but it can also arise when applicants file several applications all within a short period.

Under the judge-made law of OTDP

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.