By Dennis Crouch

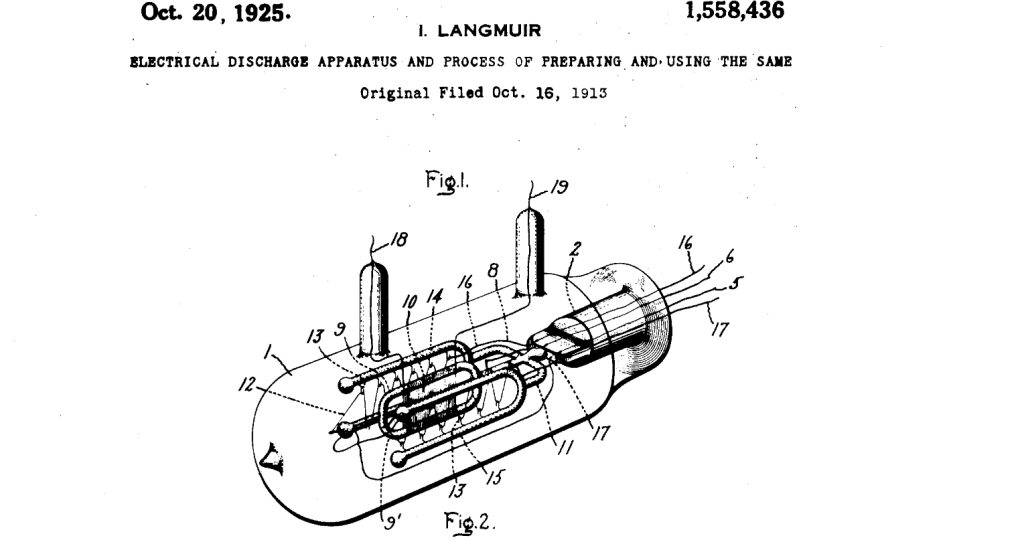

In 1931, the United States Supreme Court decided a landmark case on the patentability of inventions, De Forest Radio Co. v. General Electric Co., 283 U.S. 664 (1931), amended, 284 U.S. 571 (1931). The case involved a patent infringement suit over an improved vacuum tube used in radio communications. While the case predated the codification of the nonobviousness requirement in 35 U.S.C. § 103 as part of the Patent Act of 1952, it nonetheless applied a similar requirement for "invention."

I wanted to review the case because it is one relied upon in the recent Vanda v. Teva petition, with the patentee arguing that the court's standard from 1931 has been relaxed by the Federal Circuit's "reasonable expectation of success" standard. The decision also provides an interesting case study in the way that the court seems to blend considerations of obviousness and

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.