Search Results for: "means plus function"

Means Plus Function Claiming

Federal Circuit Affirms Finding of Indefiniteness in Dispute Over Mobile Phone and Camera Patents

Guidance on Examining Means Plus Function Claims

Means-Plus-Function: Invalidity Needs Expert Testimony

Construing the “Function” of a Means-Plus-Function Claim Element

Let me Repeat: Means-Plus-Function Element Found Indefinite Without Corresponding Structure

New PTAB Informative Decision Demands MPF Construction and Parallel Litigation Consistency

Means-Plus-Function Claims

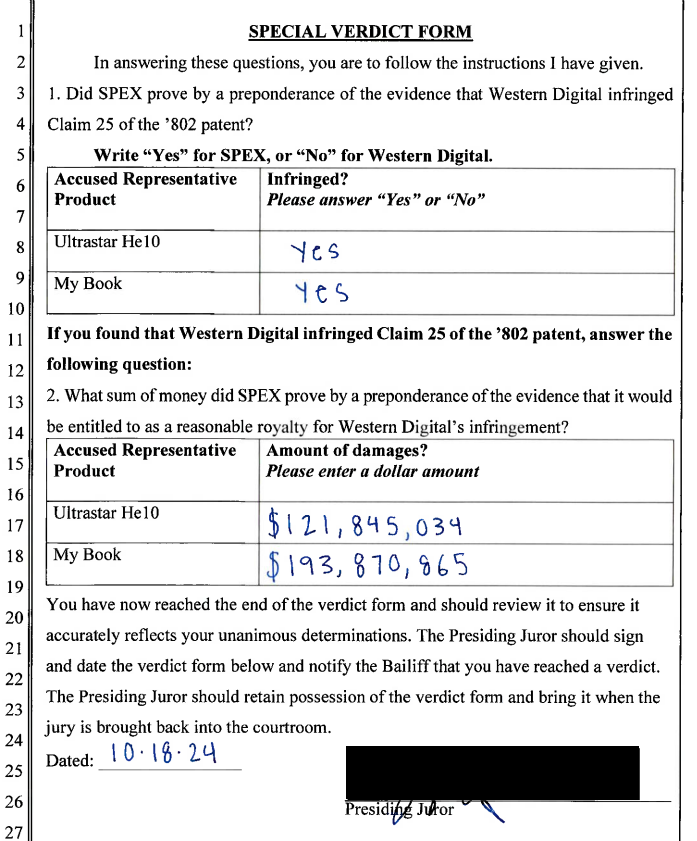

SPEX v. Western Digital: $316 Million Verdict for Means Plus Function Claim

CAFC: Means-Plus-Function Interpretations Absent Trigger Language

Williamson v. Citrix: En Banc Opinion on § 112, para. 6

By all Means: When Software Functions Lack Correspnding Structure

by Dennis Crouch

In a case highlighting the ongoing challenge of claim construction in software patents, the Federal Circuit has affirmed the district court’s determination that Fintiv’s asserted claims are invalid as indefinite. Fintiv, Inc. v. PayPal Holdings, Inc., No. 2023-2312 (Fed. Cir. Apr. 30, 2025). In the software-element two-step, the court first held that the claim terms “payment handler” and “payment handler service” should be treated as “mean-plus-function” limitations under 35 U.S.C. § 112(f) because the claim terms used lacked inherent structural meaning; and then as a result found the claims invalid as indefinite because the specification lacked sufficient structural support. U.S. Patent Nos. 9,892,386, 11,120,413, 9,208,488, and 10,438,196.

The Statutes at Issues:

- 35 U.S.C. 112(b) Conclusion. The specification shall conclude with one or more claims particularly pointing out and distinctly claiming the subject matter which the inventor or a joint inventor regards as the invention.

- 35 U.S.C. 112(f) Element in Claim for a Combination.

An element in a claim for a combination may be expressed as a means or step for performing a specified function without the recital of structure, material, or acts in support thereof, and such claim shall be construed to cover the corresponding structure, material, or acts described in the specification and equivalents thereof.