By Dennis Crouch

Alice Corporation Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank International, Supreme Court Docket No 13-298 (2014)

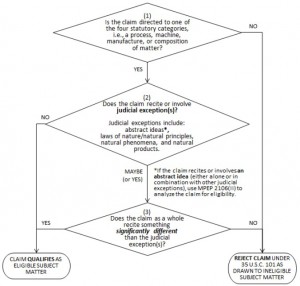

Later this term, the US Supreme Court will shift its focus toward the fundamental question of whether software and business methods are patentable. More particularly, because an outright ban is unlikely, the court’s more narrow focus will be on providing a further explanation of its non-statutory “abstract idea” test. The Supreme Court addressed this exclusionary test in its 2010 Bilski decision, although in unsatisfactory form. As Mark Lemley, et al., wrote in 2011: “the problem is that no one understands what makes an idea ‘abstract,’ and hence ineligible for patent protection.” Lemley, Risch, Sichelman, and Wagner, Life After Bilski, 63 Stan. L. Rev. 1315 (2011).

In this case, a fractured Federal Circuit found Alice Corp’s computer-related invention to be unpatentable as effectively claiming an abstract idea. See, U.S. Patent No. 7,725,375. In its petition for writ of certiorari, Alice presented the following question:

Whether claims to computer-implemented inventions – including claims to systems and machines, processes, and items of manufacture – are directed to patent-eligible subject matter within the meaning of 35 U.S.C. § 101 as interpreted by this Court.

Oral arguments are set for Mar 31, 2014 and a decision is expected by the end of June 2014. In addition to the parties, a host of amici has filed briefs in the case, including 11 briefs at the petition stage and 41 briefs on the merits. Although not a party to the lawsuit, the Solicitor General has filed a motion to participate in oral arguments and steal some of the accused-infringer’s time.

The invention: There are several patents at issue, but the ‘375 patent is an important starting point. Claim 1 is directed to a “data processing system” that includes a number of elements, including “a computer” configured to generate certain instructions, “electronically adjust” stored values, and send/receive data between both a “data storage unit” a “first party device.” The claims also include “computer program products” and computer implemented methods. The underlying purpose of the invention is to provide certain settlement risks during a time-extended transaction by creating a set of shadow credit and debit records that are monitored for sufficient potential funds and that – at a certain point in the transaction the shadow records are automatically and irrevocably shifted to the “real world.”

It is unclear to me what makes this invention novel or nonobvious and many believe that it would fail on those grounds. However, the sole legal hook for the appeal at this stage is subject matter eligibility. One thing that we do know is that CLS Bank is alleged to be using the patented invention to ensure settlement for more than a trillion dollars daily.

Important case: The claim structure here is quite similar to that seen in hundreds-of-thousands of already issued patents and pending patent applications where the advance in software engineering is a fairly straightforward, but is done in a way that has an important impact on the marketplace. One difference from many software patents is that the underlying functionality is to solve a business transaction problem. However, there is a likelihood that the decision will not turn (one way or the other) on that field-of-use limitation. In his brief, Tony Dutra argues that the key here is utility, and that an advance in contract-settlement is not useful in the patent law context.

[Brief of the US Government] The most important brief in a pile such as this is often that filed by the U.S. Government. Here, Solicitor General Donald Verrilli and USPTO Solicitor Nathan Kelley joined forces in filing their brief in support of CLS Bank and a broad reading of the abstract idea test. In particular, the U.S. Government argues that none of the claims discussed are subject matter eligible. The brief begins with an importance argument – that “the abstract idea exception is patent law’s sole mechanism for excluding claims directed to manipulation of non-technological concepts and relationships.” This notion – that the abstract idea is the final and ultimate bulwark – places a tremendous pressure on the Court to create a highly flexible test. In my view, the Government largely loses its credibility with that argument – somehow forgetting about the host of other overlapping patent law doctrines that each address this issue in their own way, including requirements that any patented invention be useful, enabled, described in definite claims, and nonobvious. The ultimate backstop is likely the US Constitutional statement regarding “Inventors” and their “Discoveries.”

The government brief goes on to endorse the approach of first identifying whether the claim would be abstract if the computer technology were removed from the method claims and, if so, move on to consider whether the computer technology limitations are sufficient to transform a non-patentable abstract idea into a sufficiently concrete innovation in technology, science, or the industrial arts. “The ultimate inquiry is whether the claims are directed to an innovation in computing or other technical fields.” The brief then reviews the precedent on this topic from Bilski, Mayo and Flook.

Addressing the computer system and software claims, the U.S. Government agrees that they are certainly directed toward “machines” and “manufactures.” However, according to the government, those claims to physical products are properly termed abstract ideas because the physical elements “do not add anything of substance.”

One interesting element from the brief is that the US Government notes that, although a question of law, invalidity for lack of subject matter eligibility requires clear and convincing evidence in order to overcome the presumption of validity. In its brief, CLS Bank argues otherwise as does Google, who actually takes time to cogently spell out the argument with citation to leading authorities.

[Brief of CLS Bank] In its merits brief, CLS Bank somewhat rewrote the question presented – focusing attention on the Supreme Court’s decisions in Mayo.

Question Re-framed: An abstract idea, including a fundamental economic concept, is not eligible for patenting under 35 U.S.C. §101. Bilski v. Kappos, 130 S. Ct. 3218 (2010). Adding conventional elements to an abstract idea does not render it patent-eligible. Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs., Inc., 132 S. Ct. 1289 (2012). The asserted claim of the patents-in-suit recite the fundamental economic concept of intermediated settlement, implemented using conventional computer functions. The question presented is:

Whether the courts below correctly concluded that all of the asserted claims are not patent-eligible.

The basic setup of the CLS Bank is the argument that a newly discovered abstract idea coupled with conventional technology is not patent eligible. CLS Bank’s point is well taken that an outright win for Alice Corp. here would involve something of a disavowal rewriting of Mayo.

[Brief of Alice Corp.] Alice Corp’s brief obviously takes a different stance – and argues first that the non-statutory exceptions to patentability should be narrowly construed and focused on the purpose of granting patents on creations of human ingenuity and that the idea behind Alice’s invention is not the type of “preexisting, fundamental truth” that should be the subject of an abstract idea test. Alice also reiterated its position that the claimed invention should be examined as a whole rather than divided up as suggested by the Government brief.

[Brief of Trading Technologies, et al.] TT’s brief (joined by a group of 40 patent-holding software companies as well as Prof. Richard Epstein) argues that the “abstract idea” test is focused on scientific truths and scientific principles. In that construct, Alice Corp’s ideas regarding the settlement system would not be seen as ineligible. TT also challenges the court to think beyond the computer as “merely a calculator and that programming merely instructs the computer to perform basic mathematical calculations. “While this may have been true of many of the applications programmed on the earliest computers over 40 years ago, it is simply not the case today. . . . Viewing computers as merely calculators is completely disconnected from the reality of where innovation is occurring today and where most innovation will occur in the future.” In his brief, Dale Cook agrees and further makes the argument that a distinction between hardware and software is illusory – citing Aristotle to make his point. [Brief of Dale Cook]. Supporting that notion is the Microsoft brief that sees “software-enabled inventions” as the “modern-day heirs to mechanical inventions. [Brief of Microsoft HP]. Pushing back on this argument, Public Knowledge seemingly shows that the entire claimed method can be implemented in seven lines of software code. Thus, while some software is complex. PK makes the argument that the software at issue here is exceedingly simple.

TT also warns against the Government’s position that a strong eligibility guideline is needed in cases such as this. In particular, explains “inventions that do nothing more than use a computer to implement time-worn concepts in obvious and traditional ways will not receive patent protection notwithstanding the fact that they concern eligible subject matter. On that note, TT asks for clarification from the Supreme Court that “Mayo does not support importation of novelty, nonobviousness, and other patentability criteria into the ‘abstract idea’ analysis.”

[Brief of ABL] The final brief in support of petitioner was filed on behalf of Advanced Biological Labs by Robert Sachs. ABL argues that a claim should only be seen as problematic under the abstract idea test when there are no practical alternative non-infringing ways of practicing the abstract idea. On that point, ABL further pushes for the notion that the test should be considered from the framework of one skilled in the art rather than simply the-mind-of-the-judge and based upon clear and convincing evidence. Pushing back against this notion is the brief of the American Antitrust Institute (AAI) drafted by Professor Shubha Ghosh. The AAI argues that the purpose of the Abstract Idea exclusion is to prevent undue harm to competition and innovation. Seemingly, the AAI contends that a claim directed an abstract idea is per se anticompetitive and that even when coupled with technology it may still be unduly preemptive. Oddly however, later in the brief AAI argues for a test that is not based upon market competition or preemption.

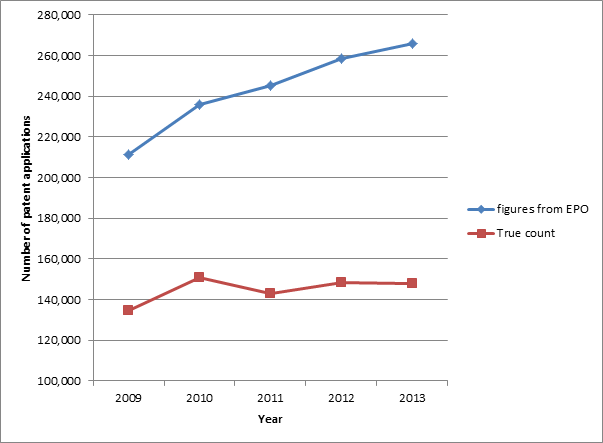

[Shultz Love Brief] A leading brief on the side of ineligibility is that filed by Professors Jason Shultz and Bryan Love on behalf of about 22 other professors. The professors make the argument that the world would be a better place without software patents. For its conclusions, the brief largely relies on the work of Brian Love, Christina Mulligan, Colleen Chien, James Bessen, & Michael Meurer. The EFF brief from Professor Pamela Samuelson, Julie Samuels, and Michael Barclay make a parallel argument: “If anything, evidence shows that the U.S. software industry is harmed by the exponential growth of vague software patents.” Without denying the problems created by software patents, Professors Peter Menell and Jeff Lefstin argue that the solution is not to rely upon the “abstract idea” test to solve that problem. IBM offers the starkest contrast to the Shultz-Love brief – arguing that the failure to clearly offer patent rights for software inventions “endangers a critical part of our nation’s economy and threatens innovation.”

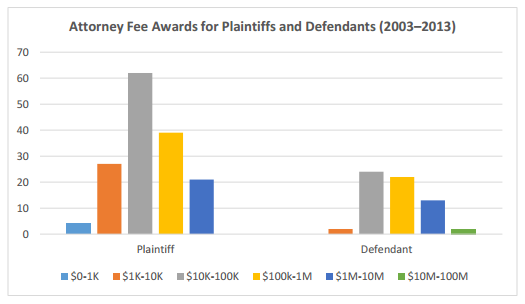

The ACLU has been more frequently involved with patent law issues and was a backer of the Myriad case. In its brief, the ACLU argues that the abstract idea exception is the patent law proxy for free speech and that monopolization of abstract ideas would be a violation of the First Amendment. That conclusion is supported by the Software Freedom Law Center & Eben Moglen. The First Amendment argument has the potential of twisting on the ACLU: if the justices fail to see that patents create any First Amendment concern then they may be more likely to support a narrowing of the abstract idea exception. Notably, in the most recent patent law oral arguments on fee-shifting, Justice Roberts arguably suggested that patents did not create any first amendment concerns.

I mentioned Microsoft’s brief earlier. Microsoft argues that software should be patentable – but not the software in this case. In particular, Microsoft agrees with the notion that simply adding “a computer” to an otherwise abstract idea does not fix the problem. Microsoft’s solution is to consider “whether the claim as a whole recites a specific, practical application of the idea rather than merely reciting steps inherent in the idea itself.” Microsoft goes on to admit that its test adds little predictability.

The Intellectual Property Owners Association and AIPLA similarly argue that software “if properly claimed” is patent eligible. On its face, that argument may not sit well with the Court who may see the “as claimed” notion designed to create loopholes for sly patent drafters whose noses are made of wax. A collective brief from Google, Facebook, Amazon, and others support this notion that patent eligibility should not turn on “clever drafting.” On an ancillary (but important) point Google argues that Section 101 defenses should be considered at the outset of most cases. cf. Crouch & Merges, Operating Efficiently Post-Bilski by Ordering Patent Doctrine Decision-Making.