Search Results for: "sas institute"

Patently-O Bits and Bytes by Dennis Crouch

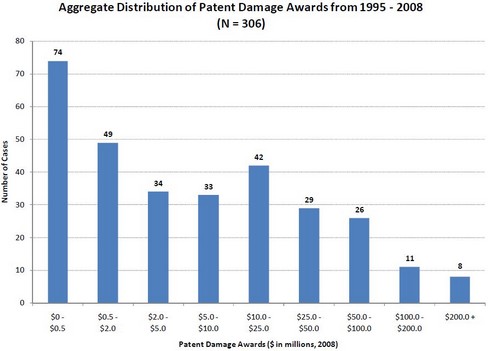

Patent Damages and the Need for Reform

Patently-O Bits & Bytes

Patenting by Small-Entities

Patently-O Bits and Bytes

Patently-O Bits and Bytes

Bilski Briefs: Supporting the Government (In Name)

Bits and Bytes No. 94

Fellow / VAP – Education – Newark, N.J.

Seton Hall University Law School is looking for a one-year Fellow / VAP to help cover IP and cyberlaw courses and to assist in the administration of our Gibbons Institute of Law, Science & Technology. The subject matter in IP is somewhat flexible, but we will definitely need someone who can cover some Internet law courses and possibly other courses. The work with our Gibbons Institute will involve helping plan and execute IP-related programs for academia and the bench and bar. The Fellow / VAP will also have an opportunity to work on his or her own research and to participate in faculty colloquia and other research-related activities. At this time the position is only for one year, although renewal for an additional year might be possible. Seton Hall University is an Equal Opportunity/Affirmative Action employer. It honors diversity and respects the religious commitments of all employees. In turn, its employees respect Catholic beliefs and values, and they support its mission as a Catholic institution of higher education.

Seton Hall University Law School is looking for a one-year Fellow / VAP to help cover IP and cyberlaw courses and to assist in the administration of our Gibbons Institute of Law, Science & Technology. The subject matter in IP is somewhat flexible, but we will definitely need someone who can cover some Internet law courses and possibly other courses. The work with our Gibbons Institute will involve helping plan and execute IP-related programs for academia and the bench and bar. The Fellow / VAP will also have an opportunity to work on his or her own research and to participate in faculty colloquia and other research-related activities. At this time the position is only for one year, although renewal for an additional year might be possible. Seton Hall University is an Equal Opportunity/Affirmative Action employer. It honors diversity and respects the religious commitments of all employees. In turn, its employees respect Catholic beliefs and values, and they support its mission as a Catholic institution of higher education.

Contact

Interested candidates should send a c.v. and cover letter to Prof. David Opderbeck and Prof. Gaia Bernstein and at gaia.bernstein@shu.edu and david.opderbeck@shu.edu.

Additional Info

Employer Type: Education

Job Location: Newark, New Jersey

Sr. Associate Director of Intellectual Property – Harvard – Cambridge, Mass.

Harvard is seeking a Sr. Associate Director of Intellectual Property to work in its Office of the President and Provost.

Harvard is seeking a Sr. Associate Director of Intellectual Property to work in its Office of the President and Provost.

Duties & Responsibilities:

Assess the patentability of new inventions disclosed by Wyss faculty and Wyss research staff. Develop and implement innovative, novel strategies to patent and protect Wyss technologies and inventions. Obtain and maintain intellectual property protection through external counsel, as appropriate. Work and communicate effectively with a broad range of constituents including Wyss faculty, members of the Wyss Advanced Technology Team, members of the Wyss Business development Team, Wyss administration, external patent counsel and industry patent counsel and other representatives of industry and government. Conduct due diligence on the I.P. of potential industrial partners and licensees, as appropriate. Assist in the development and implementation of effective strategies to commercialize the intellectual property assets of the Wyss Institute at Harvard University, as appropriate, to meet strategic program objectives. Prepare and deliver reports and presentations as needed.

Basic Qualifications:

The ideal candidate will have appropriate scientific and technical training and J.D., with a concentration in patent law. 8-12 years of experience in intellectual property management at a senior level, with advanced knowledge of current patent and licensing law and practices. Evidence of high creativity, energy and integrity as well as thoughtful judgment and decision-making. Accustomed to working in a complex environment with multiple constituencies and requiring team cooperation. Evidence of ability to establish credibility with inventors, with demonstrated maturity and sensitivity to the diverse needs of scientists, administrators, licensees and other stakeholders. Proven ability to meet deadlines on a consistent basis, coupled with outstanding administrative and organizational skills. Demonstrated leadership skills, executive demeanor and "presence". Outstanding oral and written communication skills.

Additional Information:

The Senior Associate Director of Intellectual Property will assist in the management of the Wyss portfolio, including inventions relating to life science, engineering, computer science and other inventions in various stages of development, disclosure and patent prosecution. In this position, the Senior Associate Director will work with the Wyss team in the development and execution of an overall strategy for coordinating, managing and overseeing the intellectual property (IP) assets of the Wyss Institute at Harvard University. The person will be responsible for assisting in the development and implementation of innovative strategies to protect the Wyss’s IP assets, and providing ongoing service and education to Wyss faculty and staff on issues relating to the protection of intellectual property.

Pre-Employment Screening:

Identity

We are an equal opportunity employer and all qualified applicants will receive consideration for employment without regard to race, color, religion, sex, national origin, disability status, protected veteran status, gender identity, sexual orientation or any other characteristic protected by law.

Contact

For full details and to apply, visit this link: https://sjobs.brassring.com/TGWEbHost/jobdetails.aspx?partnerID=25240&siteID=5341&AReq=38316BR.

Additional Info

Employer Type: Education

Job Location: Cambridge, Massachusetts

Executive Director: Franklin Pierce Center for Intellectual Property – Education – Concord, N.H.

The University of New Hampshire (UNH) School of Law (formerly Franklin Pierce Law Center) seeks an accomplished intellectual property professional with administrative experience and expertise to serve as the Executive Director for the Franklin Pierce Center for Intellectual Property.

The University of New Hampshire (UNH) School of Law (formerly Franklin Pierce Law Center) seeks an accomplished intellectual property professional with administrative experience and expertise to serve as the Executive Director for the Franklin Pierce Center for Intellectual Property.

The primary mission of the Center is to promote global economic development by facilitating research and training in the protection and use of intellectual property for technological innovation. The Center has an international reputation for educating global intellectual property leaders and providing pioneering intellectual property programming.

To fulfill the Center’s mission, students, faculty, and researchers work with peers and partners from governments, industry and academia across the world on research projects, conferences, and strategic collaborations. The Center houses one of the largest intellectual property faculties in the United States as well as the only dedicated intellectual property library in the nation. Through the law school’s affiliation with UNH, the Center draws on the resources of one of the nation's premier research universities. Students enjoy ready access to successful alumni working as intellectual property professionals in over 80 countries.

In consultation and collaboration with the school’s administration and IP faculty, the Executive Director will be responsible for administering the Center’s internal and external operations, including all major programs, conferences, and events. Current major programs include the International Technology Transfer Institute, the Intellectual Property Valuation Institute, and summer law programs that address a wide variety of intellectual property issues. In collaboration with administrative leadership, IP faculty, IP alumni, and other relevant stakeholders, the Executive Director will assist with the development and execution of new strategic initiatives, including collaborative partnerships with national intellectual property offices, major educational institutions, and international organizations. In coordination with other law school departments and IP faculty, the Executive Director will also facilitate the law school’s integration with UNH through the development and administration of multi-disciplinary programs and student-centered learning opportunities.

The Executive Director position is an administrative appointment with potential for associated teaching and research activities. The incumbent will report to the Associate Dean for Academic Affairs.

Applicants must possess a Juris Doctor, Ph.D. or comparable academic credentials and must have at least five years of experience in intellectual property teaching, scholarship, leadership, policymaking, practice, or industry. Applicants also must have a proven ability to communicate effectively in writing and verbally with numerous diverse stakeholders, such as academics, government officials, practitioners, students and the public, both nationally and internationally. Applicants also should have a collaborative, efficient, and professional management style and a strong commitment to working in a diverse, multi¬cultural environment.

Contact:

Applicants should submit a cover letter and resume to humanresources@law.unh.edu no later than December 15, 2012.

Additional Info:

Employer Type: Education

Job Location: Concord, New Hampshire

Guest Posts: Preparing for Mayo v. Prometheus Labs

By Professor John Golden, Professor in Law, The University of Texas at Austin

Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., No. 10-1150 (S. Ct.)

Scheduled for oral argument on Wednesday, December 7, 2011

In Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., the U.S. Supreme Court looks to address questions of whether and when certain types of medical methods are patentable subject matter. Prometheus specifically involves methods for optimizing patient treatment in which the level of a drug metabolite is measured and a measured level above or below a recited amount "indicates a need" to decrease or increase dosage levels. In 2005, the Court granted certiorari on related issues in Laboratory Corp. of America v. Metabolite Laboratories, Inc., but the Court later dismissed LabCorp as improvidently granted. In 2010, the Court reaffirmed the existence of meaningful limitations on patentable subject matter in Bilski v. Kappos, but the Court but did little to clarify the scope of those limitations.

Will Prometheus bring light where Bilski failed? Arguments to the Court invite it to further clarify the status of the machine-or-transformation test for process claims. Bilski indicated that this test is relevant but not necessarily decisive, and the Federal Circuit relied heavily on the test in upholding the subject-matter eligibility of Prometheus's claims. In the circuit's view, "asserted claims are in effect claims to methods of treatment, which are always transformative when one of a defined group of drugs is administered to the body to ameliorate the effects of an undesired condition." Likewise, a metabolite-level measurement step was found to "necessarily involv[e] a transformation." Although Prometheus's claims include "mental steps," the circuit emphasized that the inclusion of such steps "does not, by itself, negate the transformative nature of prior steps."

Prior posts provide additional background on the Prometheus case. The first wave of merits briefs have been filed. These include the opening brief for the petitioners, briefs in support of the petitioners, and briefs in support of neither party. The respondent-patentee's brief as well as supporting amicus briefs will be due in the upcoming weeks.

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS (Stephen Shapiro, Mayer Brown): Prometheus's patent claims violate Supreme Court precedent forbidding claims that "preemp[t] all practical use of an abstract idea, natural phenomenon, or mathematical formula." Prometheus's claims "recite a natural phenomenon—the biological correlation between metabolite levels and health—without describing what is to be done with that phenomenon beyond considering whether a dosage adjustment may be necessary." The claims' drug-administration and metabolite-measurement steps are merely "'token' and 'conventional' data-gathering steps" that cannot establish subject-matter eligibility. Patent protection is unnecessary to promote the development of diagnostic methods like those claimed and will in fact interfere with both their development and actual medical practice.

AMICUS BRIEFS SUPPORTING PETITIONERS

AARP & PUBLIC PATENT FOUNDATION (Daniel Ravicher, Public Patent & Cardozo School of Law): "Allowing patents on pure medical correlations … threatens doctors with claims of patent infringement" and "burdens the public with excessive health care costs, and dulls incentives for real innovation." "The Federal Circuit has latched on to trivial steps beyond mental processes, such as the 'administering' step in this case, to uphold patents that effectively preempt all uses of laws of nature." Prometheus's recitation of an "administering" step stands "in stark contrast to most pharmaceutical patents that require a 'therapeutically effective amount' of a drug be administered."

ACLU (Sandra Park, ACLU): In assessing subject matter eligibility, the Supreme Court "has focused on the essence of the claim," using a "pragmatic approach [that] allows the Court to see through clever drafting." Prometheus's insertion of drug-administration and/or measurement steps into a claim "does not alter the fact that the essence of the claim is the correlation between thiopurine drugs and metabolite levels in the blood." Further, the First Amendment bars Prometheus's claims. "What Prometheus seeks to monopolize … is the right to think about the correlation between thiopurine drugs and metabolite levels, and the therapeutic consequences of that correlation."

AMERICAN COLLEGE OF MEDICAL GENETICS ET AL. (Katherine Strandburg, NYU School of Law): The patents at issue "grant exclusive rights over the mere observation of natural, statistical correlations." They "convert routine, sound medical practice into prohibited infringement" and generate burdens and conflicts for patient care and follow-on innovation. "The machine or transformation test is inapposite … to determining whether a claim preempts a natural phenomenon." It can be too trivially satisfied without shedding sufficient light on whether claims "reflect inventive activity" or "improperly preempt downstream uses of the phenomenon."

ARUP & LABCORP (Kathleen Sullivan, Quinn Emanuel): "The patents assert exclusive rights over the process of administering a drug and observing the results…. This not only blocks the mental work of doctors advising patients, but also impedes the progress of research by seeking to own a basic law of nature concerning the human body's reaction to drugs." "Patents on measurements of nature" raise constitutional concerns by removing factual information from the public domain, thereby conflicting with patents' constitutional purpose to "promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts" and threatening to chill "scientific and commercial publication."

CATO INSTITUTE ET AL. (Ilya Shapiro, Cato Institute): This case provides the Supreme Court with an opportunity to strike a blow against the "thousands of abstract process patents which have been improvidently granted since the 1990s" and that are already adversely affecting software and financial innovation. Historically, patentable "processes" "aimed to produce an effect on matter, and these patents do not." The "indicat[ing] a need" clauses in Prometheus's claims do not even form part of a process because they do "not describe an action." Patent claims such as these, "whose final step is mental," impermissibly tread on the public domain and "freedom of thought."

NINE LAW PROFESSORS (Joshua Sarnoff, DePaul College of Law): The Supreme Court "should expressly recognize" that the Constitution requires that "laws of nature, physical phenomena, and abstract ideas" be treated as prior art for purposes of determining patentability. "Allowing patents for uncreative applications would effectively provide exclusive rights in and impermissibly reward the ineligible discovery itself." Barring claims like Prometheus's under section 101, as opposed to relying on patentability requirements such as novelty and nonobviousness, promotes "efficient gate-keeping" and "sends important signals."

VERIZON & HP (Michael Kellogg, Kellogg Huber): "It is longstanding law that a claim is non-patentable if it recites a prior art process and adds only the mental recognition of a newly discovered property of that process." See Gen. Elec. Co. v. Jewel Incandescent Lamp Co., 326 U.S. 242 (1945). "This principle is soundly based on Section 101's limitation to processes and products that are not only 'useful' but 'new.'" "[A]dding to the old process in Prometheus's patent claims nothing more than a mental step of recognizing the possible health (toxicity or efficacy) significance of the result of the process does not define a 'new and useful process.'"

AMICUS BRIEFS SUPPORTING NEITHER PARTY

UNITED STATES (Solicitor General Donald Verrilli, Jr.): The claimed methods recite "patent-eligible subject matter," and petitioners' objections to patentability are properly understood as challenges to the claimed methods' novelty and nonobviousness. By analogy with "patent law's 'printed matter' doctrine," the claims should ultimately be found invalid because, as construed by the district court, they "merely … appen[d] a purely mental step or inference to a process that is otherwise known in (or obvious in light of) the prior art." But the Supreme Court should affirm the Federal Circuit's holding on subject matter eligibility.

AIPPI (Peter Schechter, Edwards Wildman): AIPPI "encourages all member countries to allow medical personnel the freedom to provide medical treatment of patients without the authorization of any patentee." Unlike the U.S. and Australia, most countries "exclud[e] methods of medical treatment of patients from patent eligibility." When the medical-practitioner exemption of 35 U.S.C. § 287(c)(1) applies, "the courts lack subject matter jurisdiction." The exemption applies to the defendants, who "are plainly 'related health care entities.'" Thus, "the case should be dismissed for lack of federal subject matter jurisdiction."

MICROSOFT (Matthew McGill, Gibson Dunn): Subject-matter eligibility tests should not involve "pars[ing] the claimed invention into the 'underlying invention' and those aspects that are 'conventional' or 'obvious' or insignificant 'extra- or post-solution activity.'" Such parsing lacks any guiding principle that can make its application predictable. Petitioners seek an improperly "expansive application of the mental steps doctrine." "[I]f every step of a process claim can be performed in the human mind, that process is unpatentable." But the Federal Circuit has improperly "extended th[is] principle to apply to machines or manufactures that replicate mental steps."

NYIPLA (Ronald Daignault, Robins Kaplan): Innovation's "bewildering pace" argues against "rigid categorization of patent-eligible subject matter." "[T]here is no basis for excluding processes directed to analyzing the chemicals in a patient's body from patent eligibility." When satisfied, the machine-or-transformation test should decisively establish eligibility. But failure of the test should not necessarily establish ineligibility. Preemption analysis "must incorporate a critical assessment of whether the claim at issue actually claims a fundamental principle as a fundamental principle in contrast to an application of that principle."

ROCHE & ABBOTT (Seth Waxman, WilmerHale): Patents are crucial for innovation in personalized medicine and more particularly for the continued development diagnostic tests that can enable such medicine's practice. Arguments "that patents on diagnostic tests stifle innovation and basic scientific research" are "largely based on speculation, rather than sound evidence." Generally speaking, "market-driven business practices and self-enforcing market norms correct for any perceived limitations on the accessibility of patented diagnostic technologies." Congress should be trusted to provide appropriate patent-law exemptions for medical practice and research.

Patent Paralegal – National Institute of Standards and Technology – Gaithersburg, Md.

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)  is seeking a Paralegal Specialist to support NIST intellectual property management and patent prosecution. In this position, the Paralegal Specialist will interact with world renowned scientists and engineers, legal staff, and administrators that are engaged in commercializing new technology by using the patent system. The Paralegal Specialist is expected have a strong knowledge of the U.S. patent system, policies and practices of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. The Paralegal Specialist must be able to show initiative, possess exceptional verbal and written communication skills, and interact professionally and collegially with internal and external parties.

is seeking a Paralegal Specialist to support NIST intellectual property management and patent prosecution. In this position, the Paralegal Specialist will interact with world renowned scientists and engineers, legal staff, and administrators that are engaged in commercializing new technology by using the patent system. The Paralegal Specialist is expected have a strong knowledge of the U.S. patent system, policies and practices of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. The Paralegal Specialist must be able to show initiative, possess exceptional verbal and written communication skills, and interact professionally and collegially with internal and external parties.

Contact

This is a position with the United States Government and requires U.S. citizenship. All applicants must apply through this link: https://www.usajobs.gov/

Additional Info

Employer Type: Government

Job Location: Gaithersburg, Maryland