Laching-On to Inexcusable Behavior

Guest Post by Jordan Duenckel. Jordan is a second-year law student at the University of Missouri, head of our IP student association, and a registered patent agent.

The Federal Circuit released its opinion in Personalized Media Communications, LLC, Vs. Apple Inc., Docket No. 2021-2275 on January 20, 2023, in a dispute involving an alleged pattern of inappropriate conduct during patent prosecution. In a split decision, the Federal Circuit ruled that the district court did not abuse its discretion in declaring a patent unenforceable based on prosecution laches.

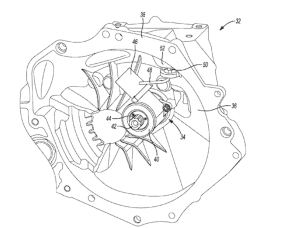

Apple FairPlay uses digital rights management (DRM) to limit user access. Specifically, FairPlay encrypts data and uses “decryption keys” to control decryption. As an additional added layer of security, Apple further encrypted these decryption keys and this further encryption is the basis for the patent infringement suit brought by Personalized Media Communications, LLC (PMC) based on PMC’s U.S. Patent No. 8,191, (the “’091 patent”). The jury reached a unanimous verdict and awarded $308 million to PMC for infringement of claims 13-16. Despite the favorable verdict on infringement, the district court eventually sided with Apple by holding the ‘091 patent unenforceable based on the equitable affirmative defense of prosecution laches. Prosecution laches requires proving two elements:

- The patentee’s delay in prosecution must be unreasonable and inexcusable under the totality of circumstances; and

- The accused infringer must have suffered prejudice attributable to the delay.

Hyatt v. Hirshfeld, 998 F.3d 1347, 1359–62 (Fed. Cir. 2021).

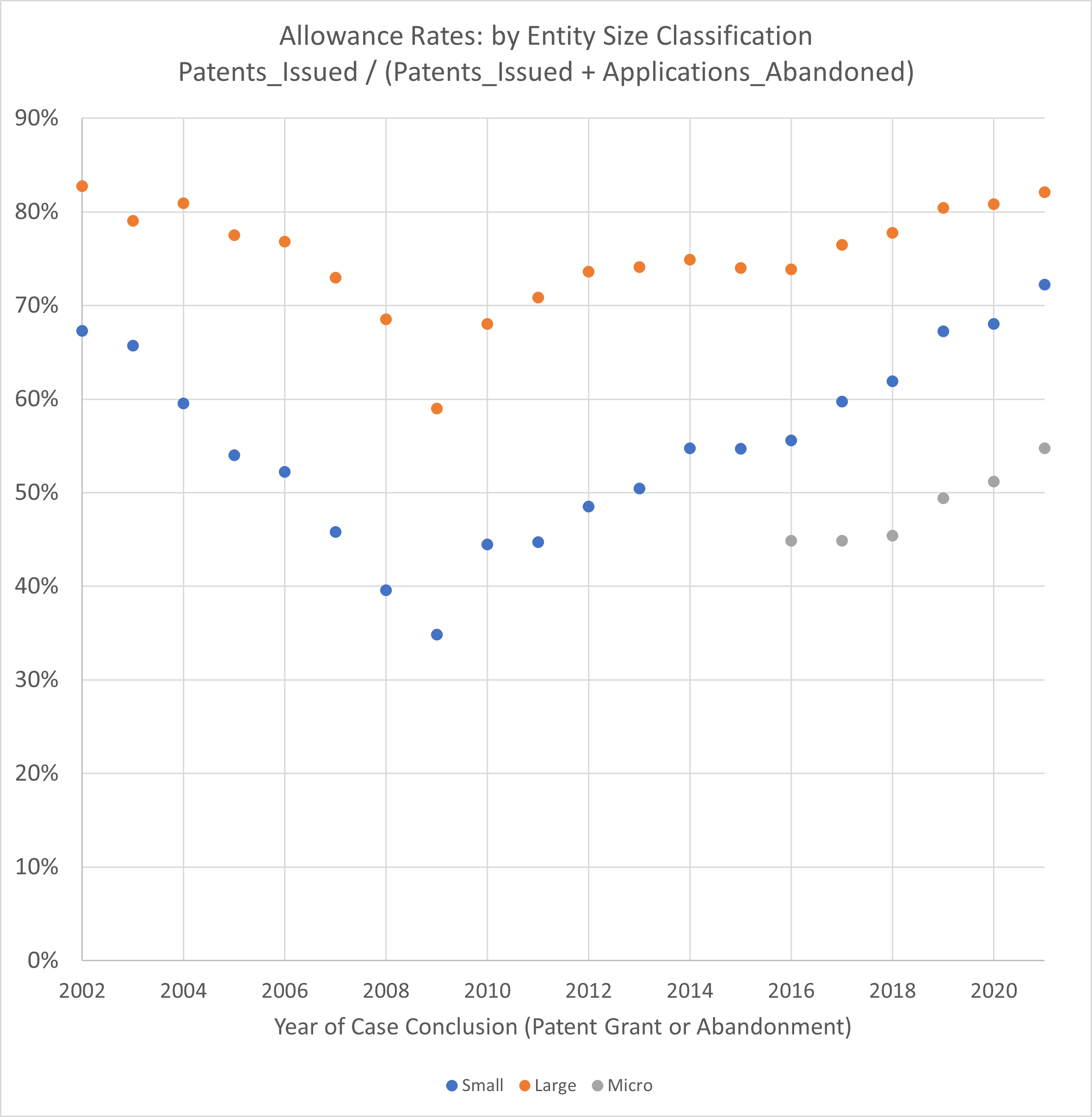

PMC’s applications were pending for 16 years before the claims were presented for examination. During that process, PMC filed several thousands of claims. PMC’s application was one of the few pre-GATT applications still pending at the USPTO, having been filed on the June 7, 1995, deadline. The legal result is that the patent term extends 17 years from its 2012 issuance date (34 years from the filing date). But, the district court concluded that equity could not maintain the result because PMCs delays were unreasonable and inexcusable.

PMC raised a number of justifications on appeal, perhaps most interesting is that PMC’s prosecution strategy was in line with the “Consolidation Agreement” it made with the PTO. The agreement was part of the USPTO’s efforts to move out these old cases. According to the procedure, where PMC was to designate “A” applications and “B” applications, with the PTO prioritizing “A” applications. Rejected claims would transfer to the corresponding “B” application and prosecution of “B” applications was stayed until the corresponding “A” application issued. This A to B process, in effect, allows PMC to delay the examination of applications and allows two chances for examination without paying a continuing examination fee.

On appeal, the majority, written by Judge Reyna and signed by Judge Chen, did not see this scheme as an excuse, but rather as further evidence of PMC’s inexcusable behavior in the prosecution process. In dissent, Judge Stark suggested that Apple had failed to show prejudice attributable to PMC’s delay.

Typically, an accused infringer can show prejudice based upon investment or use of “the claimed technology during the period of delay.” The majority concluded that Apple necessarily invested in FairPlay during the delay since it launched the product in 2003. The dissent focuses on the timeframe of the PMC’s conduct, finding that it was PMC’s pre-2000 conduct that was unreasonable while the post-2000 conduct involved more routine aspects of patent prosecution’s back-and-forth nature. But, Apple did not prove that it was prejudiced by the pre-2000 conduct.

My thoughts: Prosecution laches is a remedy meant to address abuse of the patent system and necessarily must be flexible to meet ever-changing strategic conduct. PMC employed a business strategy deliberately aimed at creating a labyrinth of patent protection extending beyond the statutory twenty years, directly stating that the goal was patent coverage extending 30 to 50 years. Further, PMC was unable to provide a legitimate purpose for the delays that aligns with the general goals of patent protection.

To me, the prejudice suffered by Apple is clear. At the time that Apple was developing FairPlay, they were unable to know the full scope of PMC’s patent protection. The chronological line drawing that the dissent favors ignores the practical effects of PMC’s ongoing deliberate business strategy. Although the unreasonable acts may have taken place prior to 2000, the impact of those actions continued well beyond. The attempt to distinguish post-2000 activities as prejudicial or not in isolation avoids the totality of the circumstances that equitable remedies like prosecution laches are meant to address.

When the PTO refuses to issue a patent, the applicant can appeal directly to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit or instead file a civil action under 35 U.S.C. 145. The Section 145 action gives the applicant the opportunity to further develop facts, including live expert testimony and cross-examination.

When the PTO refuses to issue a patent, the applicant can appeal directly to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit or instead file a civil action under 35 U.S.C. 145. The Section 145 action gives the applicant the opportunity to further develop facts, including live expert testimony and cross-examination.