Patently-O Bits and Bytes by Juvan Bonni

Garmin: Applying Facts-to-the-Law vs Law-to-the-Facts

A Walk in the Deference Labyrinth: Further Comment on Facebook v. Windy City

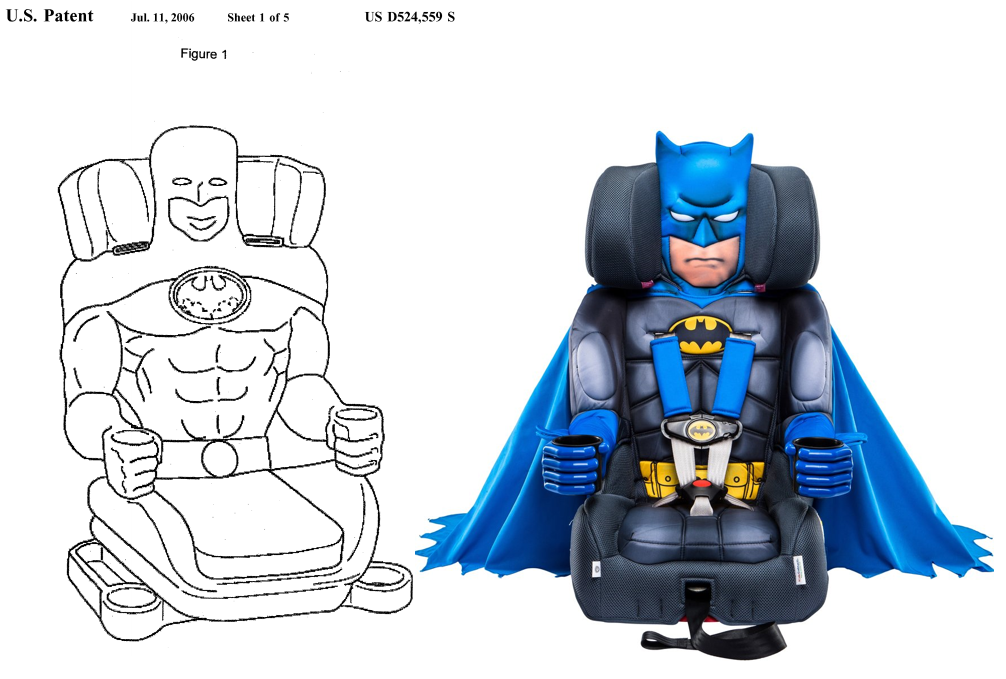

Design Patent Obviousness: How to Pick a Primary Reference

OpEd: “Blocking Patent” Doctrine Denies Valuable Innovation

Here’s a Quarter … : Continued Tricks in Defining what as a Covered Business Method Patent

AI at the USPTO

Supreme Court: What is the Role of Functional Claim Limitations?

Patently-O Bits and Bytes by Juvan Bonni

What is this Appeal About? Secrecy at the Federal Circuit

Jury Verdict on Patent Eligibility (or its Underlying Factual Foundations)

Whether the Court should overrule its precedents recognizing the “abstract idea” exception to patent eligibility under the Patent Act of 1952.

Does the PTAB Precedential Opinion Panel (POP) get Chevron Deference?

You either die a hero, or live long enough to see yourself become a villain

New PatentlyO Law Journal Essay: Implementing Apportionment

Thryv v. Click-to-Call: Accuracy vs Efficiency; Merits vs Technicality

Guest Post: Design Patents After Curver Luxembourg: Design FOR an Article of Manufacture.

Ed. Note: I summarized the Federal Circuit’s design patent decision in Curver Luxembourg v. Home Expressions in a recent post titled Federal Circuit Rejects Patenting Designs “in the Abstract.” Prof. Burstein has previously written about the case and the topic and I invited her to provide some remarks on the case. – D.Crouch

_______

By Sarah Burstein, Professor of Law at the University of Oklahoma College of Law (@designlaw)

Two quick observations at the outset:

- This decision is consistent with previously-decided case law on infringement.* (For a full run-down, see my law review article: The Patented Design.)

- This decision not consistent with the USPTO’s current novelty rule. According to the MPEP, “[a]nticipation does not require that the claimed design and the prior art be from analogous arts,” relying on an out-of-context quote (which, as the Federal Circuit pointed out, was also dicta) from In re Glavas. See MPEP § 1504.02. The court’s ruling on this point is a welcome correction and should spur the USPTO to revise its examination procedures.

This case also raises a deeper and more important question—namely, what does it mean for something to be a “design for an article of manufacture”?

Design patents are available for “any new, original and ornamental design for an article of manufacture,” subject to the other requirements of Title 35. See 35 U.S.C. § 171(a). Prior to this case, some suggested that a “design for an article” refers to merely a design that is capable of being applied to one or more articles, not a design that is in any sense “for” any particular article. Under this view, the longstanding USPTO requirement that an applicant identify an article could be viewed as a type of reduction-to-practice requirement or mere formality that should not (or even must not) limit the scope of the claim.

The Federal Circuit’s decision in Curver seems to reject that conception of the patentable “design.” Although it doesn’t fully answer the question of what it means to be a “design for an article of manufacture,” this decision is a step in the right direction.

So what happens now? The USPTO requires a design patent applicant to identify an article in the verbal portion of the claim and (the same article) in the title. See 37 CFR § 1.153. But it also instructs examiners to “afford the applicant substantial latitude in the language of the title/claim” because, under 35 U.S.C. § 112, “the claim defines ‘the subject matter which the inventor or joint inventor regards as the invention.’” MPEP § 1503.01(I).

The Federal Circuit’s decision in Curver creates incentives for applicants to seek broader titles in order to obtain broader scope. In theory, that incentive would be counter-balanced by the fact that a broader title would create a broader universe of § 102 prior art. But given how difficult it is for patent examiners and accused infringers to find relevant prior art (an issue I discuss here), that seems unlikely to be a significant deterrent to over-claiming.

The risk of prosecution history estoppel might be a more significant practical deterrent. Curver initially claimed a “design for a furniture part.” When the examiner deemed that “too vague,” Curver amended the claim to refer to a “chair.” The Federal Circuit ruled that this amendment did limit the claim. Future applicants will have every incentive to push back on these types of rejections, putting pressure on the USPTO to enunciate clearer rules about how specific article identifications need to be.

In that respect, the USPTO (and anyone who’s interested in this topic) may want to revisit the CCPA’s 1931 decision in In re Schnell. In that case, the applicant attempted to frame its claim very broadly and the CCPA rejected that attempt. In doing so, the CCPA engaged in a thoughtful and nuanced discussion about how different types of designs might lend themselves to different types of claiming and how those claims might affect a design patent’s scope. The approach taken in Schnell is not the only possible (or necessarily the best) approach, but it’s worth considering.

I’ve also been asked how Curver might affect arguments about what constitutes the “relevant article” for the purposes of § 289. (For more on that issue, see this previous post.) At this point, it’s hard to answer that question with any certainty because the Federal Circuit has still not picked a test for Samsung step one. If it adopts the test proposed by the U.S. Government in its Samsung v. Apple amicus brief, the article identification in the patent would be relevant to the damages inquiry. This approach gives applicants incentives to direct the verbal portions of their claims to he largest salable unit. See, e.g., U.S. Patent No. D852,236 (stating that the design is “for a refrigerator” but only actually claiming a small part of the shape of the interior of a refrigerator). In some circumstances, these incentives might conflict with the ones provided by Curver; it will be interesting to see how applicants balance them in future applications.

And while Curver is only directly relevant to the scope of § 102 prior art, I suspect applicants will also argue that it should also narrow the universe of § 103 prior art. But when it comes to designs, it actually makes sense for the universe of § 103 prior art to be broader than the universe of § 102 prior art. (For more on these points, see here and here).

One final note: In Curver, the panel described the asserted patent as “atypical” because “all of the drawings fail to depict an article of manufacture for the ornamental design.” But it’s actually quite common for surface-ornamentation designs to be illustrated in this way. Whether or not that is a good policy (and whether it is consistent with § 112) is another question. The answer probably depends on what it means for a surface design to be “for an article of manufacture”? Even for repeating patterns like the one claimed in Curver, it could be argued that placement and proportion are still essential elements of a design for a particular article. If that’s true, then the disembodied-fragment drawing convention also needs to be reconsidered.

_______

* Other commentators have asserted that, in the past, courts treated surface-ornamentation as designs per se. But they cited no cases in support of that assertion and I have not been able to find any. For more details, see FN 480 here.