Introducing IPRs as the De Facto Administrative Claim Construction (ACC) Procedure

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

USPTO Announces Notice of Proposed Rulemaking for Claim Construction Standard used in PTAB Proceedings

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

How the AIA is Getting Breach-of-License Cases into Federal Court

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Patently-O Daily Review – Email Subscription

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Failure to Disclose Pre-Filing Service Contract == Inequitable Conduct

by Dennis Crouch

In Energy Heating v. Heat On-The-Fly, the Federal Circuit affirmed the lower court's holding that Heat On-The-Fly's U.S. Patent No. 8,171,993 is unenforceable due to inequitable conduct.

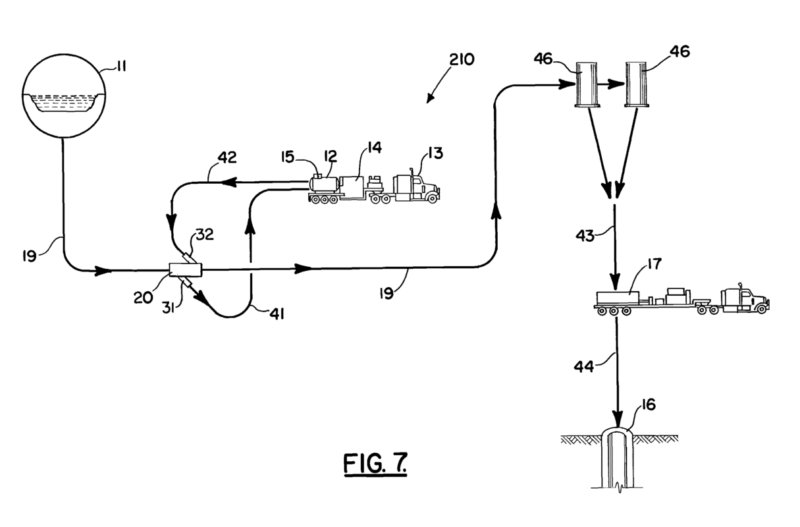

The underlying invention involves a portable system for preparing a heated water and proppant (e.g. sand) mixture for use in hydraulic fracing. Mr. Hefley, sole inventor and founder of Heat On-The-Fly, filed his priority provisional patent application back in September 2009 that eventually led to the '993 patent.

The problem: By September 2008 (one year before filing), Heafly and his company had provided his services to dozens of "frac jobs" -- collecting almost $2 million in revenue.

Mr. Hefley admitted at trial that he and his companies used water-heating systems containing all the elements of claim 1 on at least 61 frac jobs before the critical date. The court further found that invoices reflected that Mr. Hefley’s companies collected over $1.8 million for those pre-critical date heat-on-the-fly services.Those pre-filing jobs were not disclosed to the USPTO while the '993's application was pending - even though they appear quite material under 102(b) (Pre-AIA).

35 U.S.C. 102(b) (Pre-AIA) A person shall be entitled to a patent unless — (b) the invention was ... on sale in this country, more than one year prior to the date of the application for patent in the United States.Under Pfaff, the "on sale" bar requires (1) a "commercial" sale or offer and (2) the invention be "ready for patenting." Pfaff v. Wells Elecs., Inc., 525 U.S. 55 (1998). One exception to this rule is for "bona fide experiments." In particular, the Federal Circuit has held that experiments to "(1) test the claimed features or (2) determine if the invention would work for its intended use . . . will not serve as a bar." Citing Clock Spring, L.P. v. Wrapmaster, Inc., 560 F.3d 1317 (Fed. Cir. 2009).

Inequitable Conduct: In the failure-to-disclose context inequitable conduct requires clear and convincing evidence that "the applicant knew of ... the prior commercial sale, knew that it was material, and made a deliberate decision to withhold it." See Therasense. These issues are determined by the district court judge and given deference on appeal. Thus, an inequitable conduct finding should only be overturned when based upon a misapplication of law or based upon a clearly erroneous finding of fact.

Here, the patentee argued that the prior uses were "experimental" or at least he thought that they were. That argument was rejected since the prior uses included all elements of claim 1; that there were no notebooks or other experiment-like-paraphernalia; and that the uses were done openly without any attempt to hide the system or require confidentiality. (Linking these factors to Allen Engineering Corp. v. Bartell Industries, Inc., 299 F.3d 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2002)). Those elements were more than enough to overcome the experimental-use-defense.

On Attorney Advice: The court also affirmed that Hefley knew of the materiality. On this point, the interesting twist involve's Hefley's patent attorney Seth Nehrbass. Nehrbass was not permitted to testify at trial -- but would have apparently testified that the non-disclosure was on attorney advice:

HOTF asserts that Mr. Nehrbass would have testified that Mr. Hefley told him about the 61 frac jobs, but that Mr. Nehrbass decided they were all experimental uses that need not be disclosed.This testimony might have saved the patent from the inequitable conduct finding. However, it was properly excluded on prejudice grounds. In particular, up until just before trial Hefley had asserted attorney-client-privilege (including during the Nehrbass and Hefley depositions). Then, just before trial, Hefley attempted to raise the attorney-advice defense.

We conclude that the district court did not abuse its discretion in excluding Mr. Nehrbass’s testimony. The attorney-client privilege cannot be used as both a sword and a shield. HOTF was the one who asserted the attorney-client privilege in the first instance and was also the one who failed to follow up later by deposing or otherwise making Mr. Nehrbass available for examination prior to trial. HOTF cannot have it both ways. Accordingly, we conclude that the district court did not abuse its discretion in excluding this evidence on HOTF’s advice of counsel defense.Inequitable conduct affirmed. Because inequitable conduct wiped-out all of the patented claims, the court did not reach the other patent questions of "obviousness, claim construction, and divided infringement.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

When Co-Inventors Fail to Cooperate – Nobody Gets a Patent

by Dennis Crouch

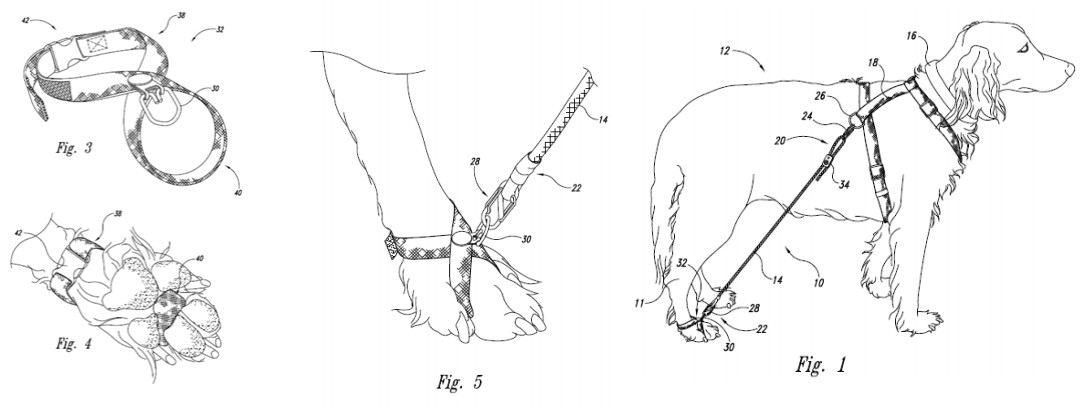

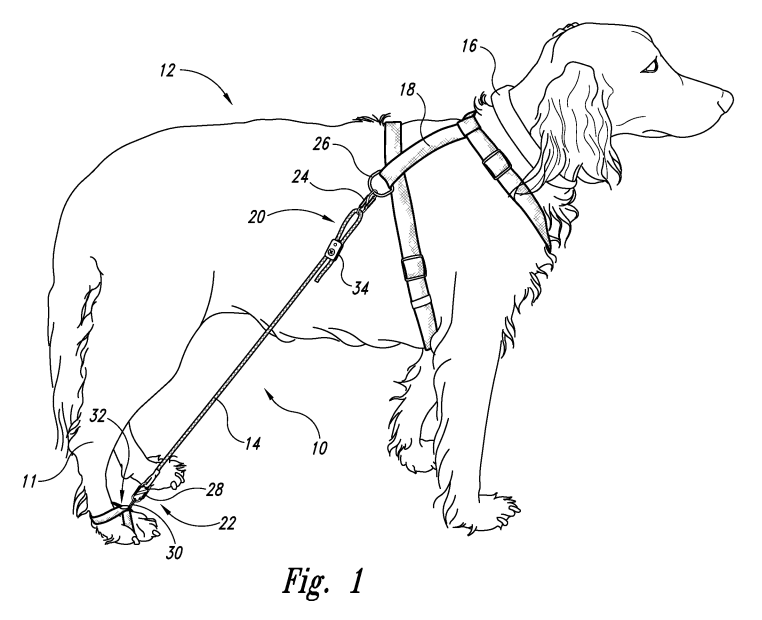

In re VerHoef (Fed. Cir. 2018) is a sad tale of a failed partnership that doomed the patent rights. The tale may be useful for anyone representing co-inventors involved in a start-up. At a minimum, a corporate entity should have been created at the get-go to hold the patent rights and mitigate later breakdowns in the partnership. Notice the drawing below - even the dog looks sad.

= = = =

For patent applications filed prior to the America Invents Act implementation, the Patent Act included an express requirement that the patent applicant be the inventor.

The named in inventor in this case - Jeff VerHoef - received some help from a veterinarian Dr. Lamb. In particular, VerHoef first designed and built his prototype harness designed to provide 'knuckling' therapy for his dog. Later, during a therapy session with Dr. Lamb, she suggested he consider a "figure 8" strap around the dog's toes. VorHoef implemented the idea then filed for patent protection -- naming both himself and Dr. Lamb as co-inventors.

Several months later, relations between VerHoef and Lamb broke-down; their original application was abandoned; and each filed their own separate patent applications. Both applications were filed on December 16, 2011 and are identical except for the names of the listed inventors.

Compare Pub. No. 20130152873 (VerHoef - at issue here) with Pub No. 20130152870 (Lamb - now abandoned).VerHoef's examiner examiner uncovered the parallel Lamb Application and subsequently rejected the claims under Section 102(f) -- alleging that Lamb's application provides evidence that "applicant did not invent the claimed subject matter." The PTAB affirmed that ruling and on appeal here the Federal Circuit has also affirmed.

For joint-inventorship, the baseline principles revolve around "conception." Individuals who conceive of features that lead to the whole invention are generally thought of as proper joint-inventors. However, the exact penumbra of what counts as sufficient contribution is at times difficult to exactly discern. Some cases suggest "every feature" while others require "significant contribution" as compared with the invention as a whole. Here the court did not need to parse-out the exact limits. Rather, VerHoef admitted that the figure-eight design (1) was contributed by Lamb and (2) is an "essential feature" of the invention.

VerHoef argued that he is the sole-inventor since he "maintained intellectual domination and control over the work" at all times and since Lamb “freely volunteered” the idea of the figure eight loop during a therapy session. ("Lamb's “naked idea was emancipated when she freely gave it to VerHoef.”)

The domination legal theory here from an old patent board decision, Morse v. Porter, 155 U.S.P.Q. 280 (B.P.A.I. 1965). In Porter, the Board wrote that if an inventor “maintains intellectual domination of the work of making the invention . . . he does not lose his quality as inventor by reason of having received a suggestion or material from another even if such suggestion proves to be the key that unlocks his problem.” Porter is cited by the Patent Office MPEP inventorship section as the basis for the following heading:

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Quarantining Bayh-Dole

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Detail Necessary for a Lawsuit: “Your Products Infringe My Patent”

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Cert Denied in Oil States Follow-On Cases

Until today, a host of patent cases have been pending before the Supreme Court -- hanging onto the coattails of Oil States. Following full affirmance of the IPR regime, the Supreme Court has now denied certiorari in those cases. The one additional case that was ripe-for-certiorari in the most recent Conference is PNC Bank National Association v. Secure Axcess, LLC, No. 17-350. The court issued no order in that case -- suggesting that it may be up for further consideration. In PNC, the substantive question is "whether . . . CBM review requires that the claims of the patent expressly include a 'financial activity element?'"

CBM Review Keeps its Narrow Scope: Narrowly Surviving En Banc Challenge

As far as I know, all of the Oil States follow-on cases denied today involved a patent whose claims had been cancelled by the PTAB. In those cases, all appeals have now seemingly been exhausted.

Cases where Certiorari was Denied:

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Twisting the Nose of Wax

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Intellectual Franchise Rights

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Taking Steps to Strengthen our Patent System

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

First Steps After SAS Institute

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

USPTO Guidance for Dealing with SAS Decision

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

President Donald J. Trump Proclaims April 26, 2018, as World Intellectual Property Day

Statement by Donald J. Trump, April 26, 2018:

On World Intellectual Property Day, we not only celebrate invention and innovation, but also we recognize how integral intellectual property rights are to our Nation’s economic competitiveness. Intellectual property rights support the arts, sciences, and technology. They also create the framework for a competitive market that leads to higher wages and more jobs for everyone. The United States is committed to protecting the intellectual property rights of our companies and ensuring a level playing field in the world economy for our Nation’s creators, inventors, and entrepreneurs. Our country will no longer turn a blind eye to the theft of American jobs, wealth, and intellectual property through the unfair and unscrupulous economic practices of some foreign actors. These practices are harmful not only to our Nation’s businesses and workers but to our national security as well. Intellectual property theft is estimated to cost our economy as much as $600 billion a year. To protect our economic and national security, I have directed Federal agencies to aggressively respond to the theft of American intellectual property. In combatting this intellectual property theft, and in enforcing fair and reciprocal trade policy, we will protect American jobs and promote global innovation.To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

The Supreme Court and IPRs – a Mixed and Messy Bag of Results

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Unclean Hands Applied to Cancel Legal Damages Award

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

SAS Institute v. Iancu: Shifting IPR and Litigation Strategies

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Oil States and SAS are out

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.