[I have substantially updated this post - correcting a couple of issues from the original and also added info from the letter from former USPTO leaders. - DC 6/1/24]

by Dennis Crouch

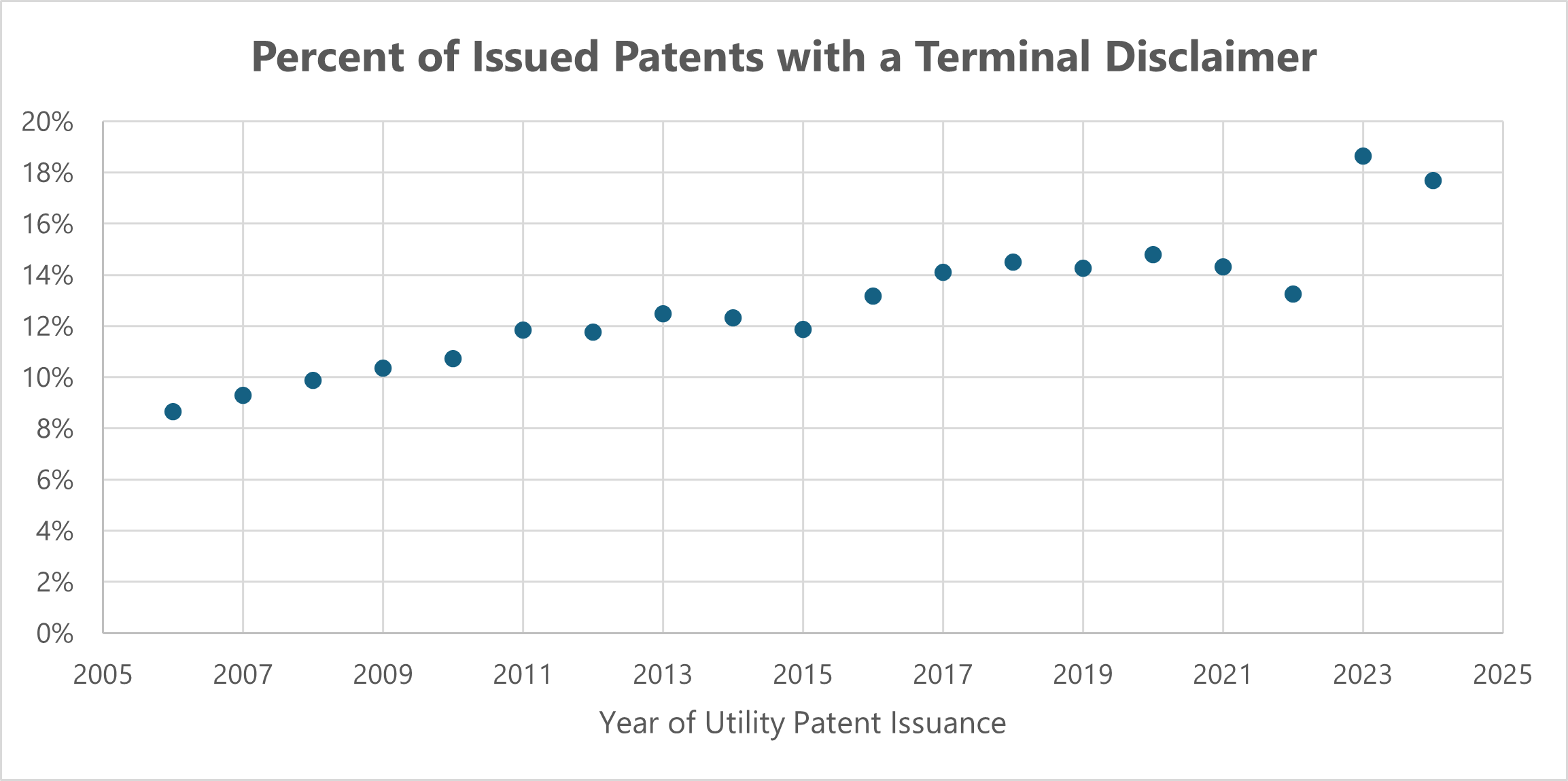

As I have previously discussed on Patently-O, the USPTO recently issued a notice of proposed rulemaking that could significantly impact patent practice, particularly in the realm of terminal disclaimers filed to overcome non-statutory double patenting rejections. Dennis Crouch, Major Proposed Changes to Terminal Disclaimer Practice (and You are Not Going to Like it), Patently-O (May 9, 2024). Under the proposed rule, a terminal disclaimer will only be accepted by the USPTO if it includes an agreement that the patent will be unenforceable if tied (directly or indirectly) to another patent that has any claim invalidated or canceled based on prior art (anticipation or obviousness under 35 U.S.C. 102 or 103). This proposal has generated significant debate among patent practitioners, with many expressing concerns about its potential impact on innovation and patent rights. It is a dramatic change in practice because the typical rule required by statute is that the validity of each patent claim must be separately adjudged. See 35 U.S.C. § 282(a).

The comment period is open until early July, but a number of comments have already been submitted. And I looked through them in order to get some early feedback. You can read the comments here

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.