by Dennis Crouch

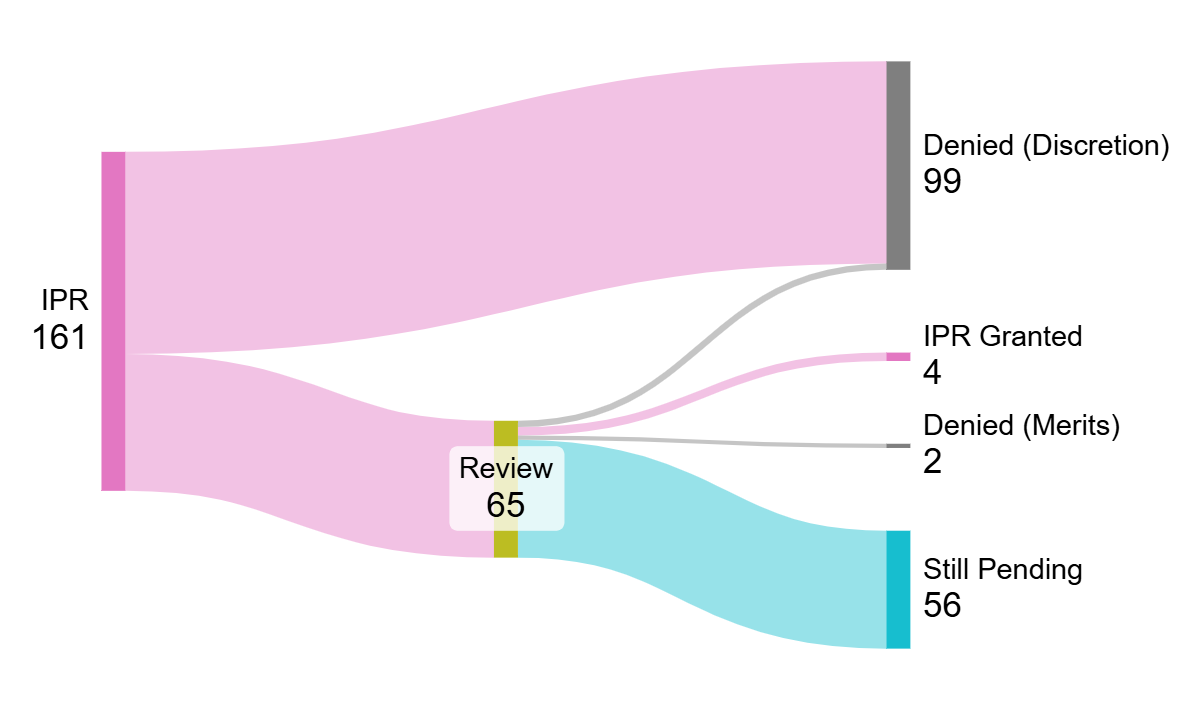

Dolby Laboratories has filed an application for an extension of time to petition the Supreme Court for certiorari, seeking review of the Federal Circuit's June 2025 decision dismissing Dolby's appeal for lack of Article III standing. Dolby Laboratories Licensing Corporation v. Unified Patents, LLC, No. 2023-2110 (Fed. Cir. June 5, 2025). The case presents fundamental questions about whether the AIA creates informational rights for patent owners about the IPR real parties in interest (RPIs) and whether the Federal Circuit has improperly narrowed the Supreme Court's standing doctrine. If the petition is filed as planned by February 20, 2026, the Court would consider it during the current Term for potential argument next Term.

A critical development not mentioned in Dolby's extension application: On September 26, 2025, USPTO Director John Squires de-designated SharkNinja Operating LLC v. iRobot Corp. as precedential, eliminating the very framework that led the PTAB to refuse adjudication of Dolby's RPI claims. This development fundamentally changes the landscape and may provide Dolby with an alternative path to relief: remand for the Board to apply the restored pre-SharkNinja standard. It will also be interesting to see whether the new Government opposes the petition.

Dolby Laboratories is a San Francisco-based technology company founded in 1965 that has evolved from its origins in analog noise reduction into a global IP licensing powerhouse with a market capitalization of approximately $6.3 billion. The company's business model relies heavily on patent licensing, which accounts for the vast majority of its approximately $1.3 billion in annual revenue. Dolby maintains a substantial patent portfolio of 10,000+ globally issued patents. Unified Patents is a membership-based organization founded in 2012 that challenges patents its members view as problematic, primarily through IPR petitions. The company operates on a subscription model where technology companies pay annual fees in exchange for Unified's patent-challenge services, creating a structure where multiple member companies may have overlapping interests in any given proceeding. This business model sits at the heart of the RPI dispute. Dolby argues that Unified's members who would benefit from invalidation of its patents should have been named as real parties in interest, which would subject them to statutory estoppel if the challenge failed.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.