- Relevant industry experience considered a plus

Contact: scenera.hr@sceneralabs.com

Scenera Research, LLC

Employer Type: Small Corporation

Job Location: Cary, North Carolina

America's leading patent law source

The Attorney/Agent will primarily be responsible for drafting original U.S. patent applications, prosecuting applications, and working closely with R&D in the processing of new invention disclosures. Opportunities also exist for managing the work of outside patent counsel and for participating in the analysis, valuation, and development of the company’s growing patent portfolio.

Essential Requirements:

- Must be self-directed and able to work independently

- Must be registered to practice before the USPTO

- Must have 2-5 years of experience preparing and prosecuting applications

- Must have computer science or electrical engineering background

Desired Experience:

Contact: scenera.hr@sceneralabs.com

Scenera Research, LLC

Employer Type: Small Corporation

Job Location: Cary, North Carolina

The firm offers a relaxed environment and excellent training with a competitive salary and benefits.

Apply: Please send cover letter and resume via e-mail to csale@young-thompson.com

Employer Type: Law Firm

Job Location: Arlington, Virginia

Job Title: Patent Agent / Technical Specialist Program- Fenwick & West LLP - Silicon Valley, CA

Job Title: Patent Agent / Technical Specialist Program- Fenwick & West LLP - Silicon Valley, CA

Fenwick & West has been a leader in technology and life sciences law since 1972. One reason for its success is its Patent Group, which is consistently ranked among the top patent practices in a general practice law firm in both the U.S. and internationally. The Patent Group has deep expertise in technology and life sciences. We have been further enhancing our technical expertise and depth through a patent agent and technical specialist program. Our patent agents and technical specialists have outstanding technical backgrounds and an interest in working in the area of patent law. Our patent agents and technical specialists focus on patent prosecution, although they also assist with litigation and corporate matters that require technical assistance. In addition, our patent agents and technical specialists are also eligible to participate in our tuition reimbursement program for law school.

Presently, we are seeking candidates with degrees in Electrical Engineering, Computer Engineering, Physics, or Computer Science. Candidates should have strong academic credentials and/or prior work experience. Candidates should also have strong written and verbal communication skills. Candidates need not have prior patent law experience and need not be registered to practice before the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Candidates that are willing to prepare for and take the registration exam to practice before the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office are eligible for a reimbursement program for this exam.

To apply, please submit a cover letter, resume and school transcript to:

Attorney Recruiting Department

Fenwick & West LLP

801 California Street

Mountain View, CA 94041

Fax 650.938.5200

Phone 650.335.4949

recruit@fenwick.com

Employer Type: Law Firm

Job Location: Silicon Valley, CA

Job Title: Patent Associate - Fenwick & West LLP - Silicon Valley, CA

Job Title: Patent Associate - Fenwick & West LLP - Silicon Valley, CA

Fenwick & West has been a leader in technology and life sciences law since 1972. One reason for its success is its Patent Group, which is consistently ranked among the top patent practices in a general practice law firm in both the U.S. and internationally. The Patent Group has deep expertise in technology and life sciences.

Fenwick and West is seeking a Patent associate with one to four years of experience preferred. Candidates should have an electrical engineering, computer science, or physics background or equivalent experience. Patent Bar eligible. Superior academic credentials, excellent verbal, written and interpersonal skills a must.

To apply, please submit a cover letter, resume and law school transcript to:

Attorney Recruiting Department

Fenwick & West LLP

801 California Street

Mountain View, CA 94041

Fax 650.938.5200

Phone 650.335.4949

recruit@fenwick.com

Employer Type: Law Firm

Job Location: Mountain View, CA

Job Requirements

• J.D. or LLM degree from high-quality law school

• A degree in EE, Physics, or Computer Science

• Admission to New York or other state bar

• Admission to practice before US Patent and Trademark Office

• At least three years experience as practicing patent attorney, with primary emphasis on patent litigation and prosecution in computer-technology-related arts

• Excellent analytical, communication and organizational skills a must

Desired Experience:

• Due diligence investigations of patent portfolios

• In-house experience or other experience managing outside counsel

• Broad technical or business knowledge of software, eCommerce, computer systems, semiconductors, telecommunications or consumer electronics.

DESIGN PATENT ATTORNEY (Full-Time / Part-Time) – Tired of the demands and long hours of big firm practice? SAIDMAN DesignLaw Group, located near the Silver Spring metro, is a small but busy intellectual property boutique that is perhaps the leading law firm in the US that specializes in industrial design protection and enforcement. We are committed to the philosophy of working hard while we’re here, and having time to enjoy life outside the firm. Therefore, evening and weekend hours are the great exception, rather than the rule.

DESIGN PATENT ATTORNEY (Full-Time / Part-Time) – Tired of the demands and long hours of big firm practice? SAIDMAN DesignLaw Group, located near the Silver Spring metro, is a small but busy intellectual property boutique that is perhaps the leading law firm in the US that specializes in industrial design protection and enforcement. We are committed to the philosophy of working hard while we’re here, and having time to enjoy life outside the firm. Therefore, evening and weekend hours are the great exception, rather than the rule.

We are seeking a motivated, full-time or part-time attorney (20-40 hours/wk) who has considerable experience and training as a patent lawyer. The ideal candidate, in addition to being drawn to our firm philosophy, is an experienced, registered patent attorney, with excellent credentials, who loves the legal side of being an IP lawyer. We desire someone who has great attention to detail, can work independently in a wide variety of IP tasks including utility patent, design patent, opinion, agreement and enforcement matters. Litigation experience is a plus, as we are handling quite a few design enforcement matters. Our 'technology' is industrial designs, which means aesthetic appearances (using design patent, trade dress and copyright laws) and light mechanical (utility patent). Experience in preparing and prosecuting design patent applications is a big plus.

PUBPAT seeks attorneys and law students with particular interest in patent law to work on various patent focused matters, in either a Pro Bono or Internship capacity. Example projects include analyzing the validity and scope of individual patents, drafting commentary on proposed legislation or regulations, and investigating the impact current patent law has on civil liberties, public health, and free markets.

Pro Bono matters are assigned based on an attorney or student's preference and availability, but require a minimum commitment of 3-10 hours per week. Semester and Summer un-paid Internship Opportunities are available for interested and qualified law students.

To inquire about current Pro Bono or Internship Opportunities, please send an email to info@pubpat.org describing your background, interest and availability. You will be contacted by a PUBPAT staff member when an appropriate opportunity becomes available. Thank you for your interest.

Job Title: Patent Prosecution Attorney

Job Title: Patent Prosecution Attorney

Job Description: Patent Prosecution Attorney. 2+ yrs of patent prosecution experience. Must have a demonstrated background and/or experience in computer-related technology and must have the ability to work independently. Excellent writing, interpersonal and communication skills are required. We offer competitive compensation and benefits package. Please submit your resume (with USPTO registration number) to info@leehayes.com for confidential consideration.

Lee & Hayes. L&H is an IP law firm that represents one out of three of the world’s top-18 U.S. patent winners (according to IFI Patent Intelligence). The work entrusted to L&H is sophisticated, technically challenging, diverse and rewarding. L&H has a casual work environment and production goals that give you a chance for life outside of the office.

Spokane. L&H is based in the All-American city of Spokane in eastern Washington State. It is a great place to raise a family. In addition to quick access to forests, lakes, mountains, and streams, the half-million citizens of the metropolitan Spokane area enjoy one of lowest costs-of-living on the west coast. According to salary.com, the cost-of-living in a place such as San Jose, CA is about 40% higher than it is in Spokane.

Thank you for your submission. Your job posting is being reviewed and should go online within 24 hours of payment. The posting is scheduled to run for 30 days.

To complete the job posting, please submit payment by clicking 'Pay Now.' Questions? Email us.

Monthly Job Posting on Patently-O Jobs

Total Fee: $200.00

Note: Customers who are not satisfied with the look of the job posting will receive a full refund.

This is a job board for patent law professionals. Employers pay a small fee to post ads. Job seekers pay nothing.

Patently-O Jobs will be available on this site and through the Patently-O Blog. The Patently-O network includes a daily readership of 15,000+ patent professionals and had well over three-million web visits in the past year (in addition to e-mail and RSS subscribers).

Pricing: A 30-day job listing costs $200. After submitting the form, you will be redirected to a page to submit payment online. For a bulk discount or long-term deal, contact us at jobs@patentlyo.com.

This is a job board for patent law professionals. Employers pay a small fee to post ads. Job seekers pay nothing.

Patently-O Jobs will be available on this site and through the Patently-O Blog. The Patently-O network includes a daily readership of 10,000+ patent professionals and is on-track for over two-million web-visits in 2007 (in addition to e-mail and RSS subscribers).

Pricing: A 30-day job listing costs $200.

Contact: dcrouch@gmail.com (ATTN: Law Jobs)

Well, we have gotten early indications from the major patent players as to how the substantive part of KSR will play out. TSM still has a place in the post-KSR world, at least according to Chief Judge Michel of the Federal Circuit and Deputy Commissioner Focarino of the USPTO. These are preliminary statements. We will not know what the Federal Circuit or USPTO really think until the first precedential opinion or interim guidelines issue. But these early comments make one wonder if KSR changes anything, particularly those like myself who witnessed the Federal Circuit's acceptance of, and reliance on, implicit TSM well before In re Kahn, DyStar, and Alza.

While the substantive impact may turn out to be minimal, KSR could have a significant procedural effect. The Court appears to have shifted the line between factual and legal parts of the nonobviousness analysis, moving what was (is?) the TSM test from being a question of fact to a question of law.

The Supreme Court in Graham established that nonobviousness was ultimately a question of law, but there were recognized underlying factual issues—content of the prior art, scope of the claims, and the level of the PHOSITA. When the CCPA, and then the Federal Circuit, started employing the TSM test, the test became another underlying factual component of the inquiry. As a result, there was not much left at the question of law level, and the Federal Circuit affirmed most appeals from rejections by the USPTO and or trials before district courts on the nonobviousness issue.

The Court in KSR introduces a procedural change, folding the TSM-like inquiry into the question of law level of the analysis. This move is most clearly witnessed in Part IV of the opinion, where Court rejects the existence of a dispute over an issue of material fact. Slip op. at 23. The Court goes out of its way to note that "[t]he ultimate judgment of obviousness is a legal determination," rejects the ability of a "conclusory affidavit[s] addressing the question of nonobviousness" to create a fact issue, and shows concern only to whether the first three Graham factors are "in material dispute." Id. In contrast, the final step, determining whether a PHOSITA would modify the prior art, is identified as a "legal question." Slip op. at 21. The earlier, general discussion of the substantive standard also supports this interpretation. The opinion focuses on what "a court" should analyze when determining whether there is "an apparent reason to combine." Slip op. at 14.

The implications of this procedural change are many. Making the TSM-like analysis a question of law facilitates more summary judgments on the issue of nonobviousness (although not as much as one would think, as I determined here). It also gives the Federal Circuit more freedom to reverse both USPTO and district court judgments on nonobviousness. This may lead us down a similar road as Markman has, giving the Federal Circuit so much flexibility that it injects even greater uncertainty into an area that is inherently uncertain, particularly after KSR. We might even end up with KSR hearings.

Admittedly, the Court does not explicitly say it is making this change. And, as the Federal Circuit has done in the past, TSM-like discussions can be framed as part of one of the first three Graham factors that have always been factual issues. However, the main focus of the opinion is on the Federal Circuit's "application" of § 103, and the language and application in KSR strongly suggest a change in the law/fact line in nonobviousness analysis (or maybe this is all just a "common sense" reading).

Chris Cotropia is an Associate Professor of Law at the University of Richmond School of Law and is part of the School's Intellectual Property Institute. Professor Cotropia was counsel of record and a co-author on the Brief of Business and Law Professors as Amici Curiae in Support of the Respondents in KSR.

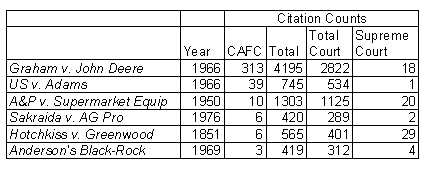

Part of the legacy of KSR will depend upon how the case is treated by the Federal Circuit (CAFC). Graham v. John Deere is the seminal patent case on obviousness, and is cited by most patent decisions involving the question of obviousness. Cases like Sakraida and Anderson's Black-Rock are much less likely to be relied-on. Sakraida, for instance, is fifty-times (50x) less likely to be cited by the CAFC than Graham -- even though Sakraida represented (until 2007) the Supreme Court's most recent pronouncement on obviousness. Sakraida's low-level influence has waned in recent times. For instance, the cow-dung case has only been cited once by the CAFC in the past decade. (in DyStar).

The table above shows the number of Shepard's citations found for the Supreme Court's set of obviousness decisions. Total citations include all known citations while "total court" citations include only instances where the case was cited in a court opinion. The No. 2 case (in CAFC citations) is US v. Adams. That case is notorious as the only nonobviousness case -- i.e., were the Supreme Court found the claims nonobvious.

The KSR Opinion has much more meat than Sakraida, but the case will never challenge the canonical status of Graham v. John Deere. Of course, the question of KSR's legacy is now in the hands of the CAFC.

KSR Int'l v. Teleflex, Inc., 550 U.S. ___ (2007).

In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court rejected any notion that the concept of obviousness in patent law can be rigidly or narrowly defined -- holding that "the obviousness analysis cannot be confined by a formalistic conception." However, the opinion does not radically change the notion of obviousness or immediately invalidate a wide swath of already issued patents.

The question of nonobviousness comes-up in Section 103 of the Patent Act. That section declares that a patent shall not issue if "the differences between the subject matter sought to be patented and the prior art are such that the subject matter as a whole would have been obvious at the time the invention was made to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which said subject matter pertains."

But what is "obvious"? Certainly, this amorphous term has continuously stumped engineers and scientists for the past 50+ years. One particular issue involves combination inventions that take various existing elements and combine them in a new way. When is such a combination obvious? In an attempt to provide improved notice and regularity, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) introduced a test that holds a combination invention is nonobvious absent some teaching, suggestion, or motivation (TSM) to combine the various parts together.

In KSR, the Supreme Court began by rejecting the CAFC's test for obviousness:

"We begin by rejecting the rigid approach of the Court of Appeals. Throughout this Court's engagement with the question of obviousness, our cases have set forth an expansive and flexible approach inconsistent with the way the Court of Appeals applied its TSM test here."

At this point, I would have expected the Court to obliterate the past twenty-five years of obviousness jurisprudence and begin again with a clean slate. It did not do that — rather, the opinion appears to simply refine the particulars of how prior-art can be combined and when a "combined patent" will be seen as obvious. Without explicitly saying so, the Court's opinion appears to affirm the CAFC's more recent pronouncements of a flexible test of obviousness. Dystar, Alza.

Patent Value: In the short-term, this case reduces the average value of patent holdings. Courts should find it easier to invalidate patents based on expert testimony and the jury's concept of obviousness. The story also becomes more important -- and attorneys who can tell an "invention story" will be in demand. During prosecution, inventors and experts should get their pens ready to sign declarations of patentability.

Preliminary Gems:

Notes:

KSR v. Teleflex, 550 U. S. ____ (2007): In a unanimous opinion authored by Justice Kennedy, the Supreme Court held that the Federal Circuit's "narrow" & "rigid" TSM test is not the proper application of the nonobviousness doctrine of Section 103(a) of the Patent Act.

"To facilitate review, [the obviousness] analysis should be made explicit. But it need not seek out precise teachings directed to the challenged claim's specific subject matter, for a court can consider the inferences and creative steps a person of ordinary skill in the art would employ."

"A patent composed of several elements is not proved obvious merely by demonstrating that each element was, independently, known in the prior art."

"There is no necessary inconsistency between the [TSM] test and the Graham analysis. But a court errs where, as here, it transforms general principle into a rigid rule limiting the obviousness inquiry."

Microsoft v. AT&T: With a 7-1 majority, the Supreme Court has ruled in favor of Microsoft in its extended fight againt extraterritorial application of US Patent Law -- holding that Section 271(f) of the Patent Act does not extend to cover foreign duplication of software. Justice Stevens dissented.

Opinions:

You should be cautious and retain your USPTO E-filing acknowledgment. Filings should be immediately available for review on Private PAIR.

Finally if EFS-WEB is not working, the practitioner should be ready with an alternative method of filing such as fax or snail mail.

National Stage Evidence: The PTO has also given notice that the EFS-WEB acknowledgment receipt will be sufficient to show that correspondence submitted in a national stage application was actually received by the Office.

Link: Read the USPTO Notice

When no less an authority than Hal Wegner of Foley and Lardner starts worrying about the current direction of the Supreme Court on patent issues, it’s time to sit up and take notice. I have heard some of these concerns in the past few years, especially in the wake of the eBay injunction case. But when Hal sent around his widely-read “top 10 cases” email recently, I could see that his outlook had taken a serious turn for the worse. Here are some quotes from the recent Wegnerian missive:

“eBay philosophically piggybacks off an anti-exclusionary right climate in the electronics/software/manufacturing industries that has had a constant, anti-patent drumbeat in the academic and business communities and in the mainstream press. The Court has listened. . . .

[A] decidedly anti-patent core nucleus from the Douglas era is reforming at the Court that - save for Justice Stevens - had disappeared in the wake of the 1980 Chakrabarty and 1981 Diehr decisions . . . .

I believe this is a fairly mainstream view, at least among some chem/biotech/pharma practitioners. And despite how much Hal knows about all things patent (things he has generously shared with me and other academics over the years), I have to disagree with his assessment. Even more, though, I am worried about the larger implications of these views. The wedge between the pharma/biotech/manufacturing and the software/electronics views of the patent world is on one level just a normal development in a vibrant and growing field. But beyond a certain point, it is not a good sign. This is especially true when it is combined with the view that the current Supreme Court is anti-patent. Taken together, this attitude reminds me of the bad old days, the days whose shadow we in this field have only recently emerged from: the days when patent lawyers huddled together, defensively, while a hostile world seemingly bent on the destruction of this area of law (and these incentives for inventors) lobbed random attacks their way.

I think this period, which the field survived (some would say, just barely), casts a long shadow over today’s developments. But in my view at least, there is much more sunlight today than in the bad old days of the Douglas-Black anti-patent jihad. We have not seen, in any of the Court’s recent opinions, discussion of patents as “monopolies,” along the lines of Justice Douglas’ concurrence in Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co. v. Supermarket Equipment Corporation: “Every patent is the grant of a privilege of exacting tolls from the public. The Framers plainly did not want those monopolies freely granted.” Compare this with a statement from the unanimous opinion in one of the “new wave” of Supreme Court patent cases, the Festo case from 2002:

Each time the Court has considered the doctrine [of equivalents], it has acknowledged this uncertainty [over effective claim scope] as the price of ensuring the appropriate incentives for innovation, and it has affirmed the doctrine over dissents that urged a more certain rule.

In my view, it makes no sense to equate Douglas’ fifty year old dictum in a concurrence with this recent statement from a unanimous Court opinion. To reiterate: the recent statement of binding law talks of preserving “incentives for innovation,” and not hunting down spurious monopolies.

If there is an “Exhibit A” in Hal’s alarmist argument, it is the recent eBay opinion. Indeed, eBay seems to be the driving force behind most of the anxiety over the current direction of the Supreme Court. On one level, this is perplexing; after all, an opinion extolling “traditional principles of equity – the heart of the Court’s holding in eBay – hardly seems like a radical, “anti-property” legal ruling. But I think that the concerns Hal expresses have a deeper cause: the divergence in interests, and growing split, between pharma/biotech and electronics/software industries. I will return to this theme momentarily. But first, a few words about the post eBay environment are in order.

Recent cases show that for the most part the fears of the patent bar in the immediate aftermath of eBay are not being realized. (Joe Scott Miller's running web page tally of post-eBay cases shows this. As Professor Miller’s data show, district courts have granted plenty of preliminary and permanent injunctions following eBay. Injunctions have been denied in cases weak on the merits, which of course is nothing new; and in a few cases where patents provide disproportionate leverage or are asserted by entities that do not contribute in any appreciable way to innovation: exactly the result intended in the eBay opinion, in my view. And note to Hal: since pharma/biotech firms are real innovators, they have nothing to fear from eBay.) For the most part, people in the patent world recognize this: how can one rationally complain about the continued increase in patent applications while arguing that eBay has significantly undermined the value of all patents? If that latter argument were true, application volume would be dropping, not rising. The opinions in Warner-Jenkinson and Festo, other opinions, and even the remarks about the need not to upset the apple-cart in the oral argument in KSR show a concern with balance that belies a wild-eyed anti-patent bias.

My reading of the evidence – including eBay and its aftermath – is that this is a pro-business Court. I think the Supreme Court has created, overall, a very moderate body of patent law in recent years. (Examples: taking claim construction from juries; preserving the doctrine of equivalents, first from a frontal attack, and then by preventing prosecution history estoppel from swallowing it; trying to draw a reasonable line in the on-sale bar area; etc.) It has absolutely not shown itself to be systematically “anti-patent.” What it has done is to try to keep order and balance in a fast-paced field, weighing the interests of various branches of industry and various users of the patent system. This is, by all assessments, a pro-business Court. It would be shocking if the Court had deviated from this baseline commitment in one important branch of business cases, those involving patents. In my view, it has not.

The Supreme Court’s Real Concern: The Federal Circuit

Later in his letter, Hal has this to say:

[T]he passage of a generation and an open and some would say deserved hostility of the academic community toward the Federal Circuit has transformed this Court of Appeals into just that, an intermediate appellate court where the Supreme Court now pays perhaps closer attention to its jurisprudence than any regional circuit, except possibly the Ninth Circuit.

Here Hal is onto something significant. The real target of the Supreme Court’s caselaw seems to be, not the patent system generally, but the jurisprudence of the Federal Circuit. It is crucial to keep this in mind: whatever one thinks of the Federal Circuit, or of how much its caselaw needs “correcting,” targeting that Circuit is not the same as targeting patents or patent law generally. This is a vital distinction between the “bad old days” of the Douglas/Black era and today.

The Federal Circuit may well be the “new Ninth Circuit.” Despite the Federal Circuit’s overall success in stabilizing patent law, and setting it on a more coherent course, in my opinion the legal rulings of that Circuit often cause unnecessary confusion. Vacillation and variation are well-recognized in a number of important areas: claim construction, the “written description” requirement, means-plus-function claims, inherency, and product-by-process claims, just to name a few. There may be good reasons for some of this variation. They may be structural, having to do with the difficulty of the subject matter, or the absence of competing ideas and different perspectives caused by being the only appellate court in the area. (For some original analysis of these issues, and a sure-to-be-provocative proposal, see Craig Alan Nard and John Duffy’s recent working paper calling for patent issues to be spread among two or more appellate circuits: “Rethinking Patent Law's Uniformity Principle.”) Perhaps the Federal Circuit’s problems are more idiosyncratic, having to do with the composition or workings of this particular group of judges. Whatever the cause, the Supreme Court, in stepping up the scrutiny on that Circuit, is just doing its job of supervising and tending the overall functioning of the federal court system.

So in my view it makes no sense to criticize the Supreme Court, which is trying to steer the Federal Circuit in the right direction. It is especially perplexing to hear some of the same voices complain about the Supreme Court as also complain about the variations in Federal Circuit cases. These dual complaints (“the Federal Circuit needs a lot of work” and “The Supreme Court is anti-patent”) make the patent community sound incredibly negative. It reminds me of the old Woody Allen joke about the food at summer camp: “The food was awful. And the portions were small too.” The Supreme Court is the only force actively working to steer the Federal Circuit onto a reasonable course. For those of us who believe patent law is an important and worthy field of law, we ought to be grateful for the attention.

To summarize: I believe the Court looks at patent cases from a centrist, inclusive, business-oriented perspective, which is a far cry from saying they are anti-patent. Criticism of individual patents, as in the KSR oral argument, or the dissent from the dismissal of certiorari in Metabolite does not in my mind reveal an underlying anti-patent bias. It does reveal a concern with the quality of some individual patents – which is a different concern.

But of course, in this the Court is not alone. Although it is tempting to say that those who are “anti-bad patents” are really in some sense “anti-patent,” I would disagree. As this is the core of the contentious divergence between pharma and electronics mentioned earlier, I turn to that issue now.

Looking at the Bigger Picture: When Molecules and Electrons Collide

It is no secret that the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries have very different interests than those of electronics and software. Pharma products are typically covered by one or at most a handful of patents; the “billion dollar molecule” means that in pharma, there is such a thing as “the billion dollar patent.” Not so in electronics and software. Hundreds or thousands of patents may read on individual features of a complex microprocessor, consumer electronics device, or software product.

Because the Supreme Court’s cases have in recent years tried to strike a balance between various aspects of the patent system, they have of necessity waded into this area of contention. In many ways, concerns about the Supreme Court are really only part of a larger set of concerns on the part of pharma/biotech. The people who make their livelihood from these industries appear to me to be worried that the newfound efforts at “balance” are coming directly at their expense – that whatever balance the system as a whole may be gaining is coming at the cost of certainty and stability in their core areas of concern.

I want to make two points about that. First, I do not think that this is a “zero sum game.” I think the patent system can be tweaked and adjusted so as to address the concerns of the electronic/software industries, without undermining the economic position of pharma/biotech to any appreciable extent. Second, I believe that this “us against them” mentality could have some serious negative consequences. (This mentality is on prominent display in a recent brief filed by Eli Lilly in the Microsoft v. AT&T case in the Supreme Court – a frontal assault on the patentability of software, by a large pharmaceutical firm. Fortunately, it is unlikely the Court will take much notice, since the case centers on a discrete section of the Patent Act relating to infringing exports, and has nothing whatsoever to do with Section 101 issues.) Whatever the strains of bringing disparate industries under “one big patent tent,” based on what we know now they are worth it, compared to the alternative.

On the first point: despite real friction in recent years, I believe both sets of industries can be accommodated in a reasonable patent system. The key point is for the pharma/biotech industries to recognize that the software and electronics industries are not anti-patent, they are anti-bad patent. There is a world of difference between these two. (If you don’t believe that, look in on the debates between rabid open source and “free software” advocates and those trying to defend the value of patents in the software and other industries. It is maddening for software industry people that they are attacked as club-wielding monopolists by those who attack patents from within the software industry, and then accused by pharma of being latter-day acolytes of the Douglas/Black anti-patent school!)

On the other side, those in the electronics/software industries need to put themselves in the shoes of pharma/biotech. As carefully as “patent trolls” strategize to acquire patents that aim directly at the Achilles heels of an electronic or software product, so do generic drug companies take aim at the patents of pharma/biotech. Any tool designed to “weed out” weak patents from the hands of trolls can and will be turned around and used against pharma/biotech patents, by generic drug firms only too happy to swoop in after all the hard (and expensive!) work is done and cash in on a pharmaceutical product or therapy. And unlike in the electronics/software industries, this cut-throat competitive game goes on in pharma/biotech in an industry that comes under intense public scrutiny concerning drug pricing, marketing and safety. Sometimes it seems as if the press and other observers are doing their best to turn Big Pharma into the next tobacco or asbestos industry – ironic when you realize that pharma/biotech is at heart all about saving and extending lives, not endangering them. Against this backdrop, it is easy to see why the pharma/biotech industries are concerned. Patent law is one of the last bastions against a fairly hostile onslaught. Of course they are worried about any weakening along this front.

One “solution” that might seem commonsensical is to split the patent system. Although it is tempting to do so, to “send the combatants to opposite corners of the ring,” in my mind we don’t yet know enough about how this would work to advocate it seriously. There are too many open questions: would the patent office issue two separate types of patents? How would the borderline between them be policed? Would they be enforced differently? What standards of validity and infringement would apply to each? And on and on. These issues will have to be studied very carefully before one can confidently advocate a truly split patent system. Maybe something along these lines will make sense someday. In the meantime, piecemeal, careful reform of individual patent doctrines and procedures seems a far more sensible course.

Because of this uncertainty, it seems to me divisive and dangerous for pharma/biotech to alienate potential allies. The electronics and software industries are after all huge players in the economy, and they have earned a substantial place at the bargaining table over patent issues. This new reality is being felt in the patent world, and will continue to be felt. The old days of the large east coast law firms and a few dominant (mostly east coast) companies setting patent policy are over. This is a sign of success: our economy is growing and changing, and patents continue to be important in many sectors. Public policy will and should change accordingly. That’s the way the system is supposed to work.

The downside of divisiveness is also worth considering. Do the pharma/biotech industries want to drive electronics/software companies into a political alliance with generic companies? Do pharma/biotech firms want to embrace the “patent trolls,” and risk associating themselves with entities seen as interested only in exploiting weaknesses in the system to make money than in actually pushing ahead with useful new technologies? (The lessons of the tort reform movement are relevant here: it may take too much time, but eventually those who use the legal system only to extort money from productive sectors of society will be shut down. Why would you want to ally yourself with players operating under a surefire expiration date?) These kinds of political bedfellows pose serious risks all around, in my view. Better to compromise over the details of patent reform than risk open warfare of this sort. That could be bad for everyone who believes the patent system is a fundamentally worthwhile institution.

Going Forward

To summarize: What worries me about Hal’s views is that they overemphasize the shadows currently cast over the patent system, and invite comparisons with an era that I think was very different. And to the extent Hal’s views exacerbate a split between powerful industry groups with interests in the patent system, they point us in a dangerous direction n.

I may not agree with my old friend Hal in this matter. But the point is that we do (I think) both share an important fundamental belief in the viability and continuing potential of the patent system. (That’s one of the many things he passed along to me in my early days in this field.) In my view, the Supreme Court shares this view too. We need to continue to work with the Court, and with each other, in the good faith belief that we are all engaged in a worthy common enterprise. What do you say, Hal?

Note: Robert Merges is the Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati Professor of Law and Technology and Director or the Berkeley Center for Law & Technology.

In the briefs now before the Court, software-and information generally-is characterized as an ethereal construct, barely capable of being controlled or understood. In its amicus brief, Autodesk calls information "meta-physical." The Software & Information Industry Association describes information as "purely intangible." According to Microsoft, information is "abstract," and is "floating in the ether." Information has been so denigrated that AT&T, who holds the patent on the software method relevant to the case, claims that "software is not 'information.'"

Colloquially speaking, information is hardly a new concept. Perhaps this is why the briefs assume it is reasonable to use a dichotomy pulled from Aristotelian philosophy: optical disk as "substance" versus computer program as "accident." But like physics, chemistry, and other topics of interest to the ancients, information has become a science, and it should be discussed as a science.

One prerequisite of science is the ability to isolate an object of study from the complicating influence of the environment. The first quantitative understanding of physics came only after natural philosophers turned their attention to the unimpeded motions of planets and pendulums, and the modern era of chemistry, it is argued, began when a French lawyer isolated the process of combustion. In biology, evolution was discovered only after the study of an isolated island ecosystem. Just as physics, chemistry, and biology were once "proto-sciences," so too was it difficult until recent decades to speak of a science of information. Information had always been bound up with books and thoughts, where its quantitative study would have been unimaginable. Digital computers, though, have given us both the ability and the motivation to study information in a nearly isolated form.

AT&T's denial that software is information is strange, and even disappointing, because it was at AT&T's own Bell Labs that the scientific study of information originated. See Wiki. In the intervening half-century, the physical properties of information have been studied thoroughly. Lawyers and the courts cannot be expected to understand this young science in detail, but they should not assume that there is nothing to understand.

One of the most profound results of the scientific study of information is that information, like other physical phenomena, is governed by the laws of thermodynamics. In particular, information has the properties of the thermodynamic quantity known as "entropy." See Wiki. These physical laws impose real limitations on the storage and manipulation of information, without regard to whether the information is embodied in magnetic dots, microscopic pits, punched cards, or even radio waves. Many of these laws and limitations are summarized in Michael P. Frank, "The Physical Limits of Computation," Computing in Science & Engineering (May/June 2002) at 16-26, available here.

The science of information need not be studied in depth to appreciate how uninformed many of the arguments to the Supreme Court have been. A comparison between computer software and "design information" (such as CAD/CAM codes, blueprints, instructions, or recipes) is repeated among the briefs. The desired inference, spelled out by amicus Amazon, is that there is "no scientific basis" for distinguishing between them. This inference, though, is incorrect. In the study of information, as in thermodynamics, there is a fundamental distinction between actions that are "reversible" and actions that are "irreversible." An irreversible process is one in which information is lost. For example, overwriting data in memory, as is done continually in a computer system, is not reversible. Copying a computer program from a master disk onto a blank portion of a hard drive, though, is reversible: even if the master disk is lost, its information can be restored using the information from the hard drive, and the hard drive can be restored to its original blank state.

Contrary to Amazon's arguments, then, computer software can be scientifically distinguished from design information, because using design information to produce a product is irreversible. A manufactured product cannot be changed back into CAD/CAM codes and raw materials. A computer with Windows installed, though, can be changed back into a computer with a blank disk and an uninstalled copy of Windows.

The amicus law professors have argued that compressed or encrypted information is "useless gibberish." Again, the science of information provides a helpful insight: compressing and encrypting data are both reversible processes. No relevant information is lost, since the data can be decompressed and decrypted to its original form.

Microsoft provides a nearly Biblical description of its Windows software as "abstract information" that "lacks physical existence" but to which Microsoft has "given a physical manifestation" as a "golden master." See John 1:14 ("And the Word was made flesh... and we beheld his glory."). How the first manifestation of Windows was pulled from the ether, though, is irrelevant. The issue before the Court relates only to what happened after Windows was originally compiled, and it is clear that any copies made thereafter were the mundane result of a reversible copying process.

Thus, the distinction in Federal Circuit case law between software, which can be a "component," and design information, which cannot, is a valid distinction. It can be seen as a question of whether supplying the alleged component is reversible: information is a component if and only if it can be added and removed in a substantially reversible way. This parallels our understanding of mechanical components: most parts can be both added to and removed from a mechanical device. Of course, gray areas would remain (compiling source code into object code, for example, is not entirely reversible), but they remain in other technologies as well.

Information has other properties that allow it to be easily understood as a "component." Like mechanical components, information can be traced to its source (to determine who is liable), and it can be counted (to measure damages). Indeed, information can be far easier to trace to its source than anything made of molecules. A U.S. manufacturer could deny that it exported any physical part of an accused product: a connector made overseas may look exactly like one made domestically. Microsoft, though, could hardly deny that it was the original source of the Windows program: the probability that someone would arrange so many megabytes of information the same way as Microsoft, without copying, are astronomically small.

Normally, a single copy of a program is provided on each disk or on each computer. This makes it easy to count the instances and the location of a software "component" to determine damages: the number that are made in the United States, the number that are exported, and the number that are made abroad. Even in other, more complicated scenarios, information theory provides ways of characterizing the number of copies that exist (using, for example, measures of "redundancy" or of "mutual information").

Without proper guidance, the Supreme Court is likely to perpetuate proto-scientific characterizations of software. Information, such as the information used to store and transmit software, has well-understood physical properties. Because of those properties, software can be logically and consistently treated as a "component" under the patent laws. Whether those properties imply that software merits patent protection is open to debate, but neither side in that debate should disregard the scientific understanding of information in the hope of a victory based on ignorance.

Note: Jeff Steck is a patent litigator at McDonnell Boehnen Hulbert & Berghoff in Chicago. He studied physics at the University of Chicago.