by Dennis Crouch

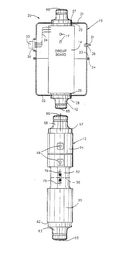

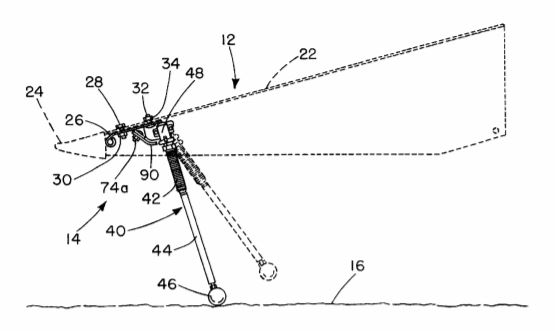

Functional claim language has long been a mainstay of U.S. patent law. In the historic case of O’Reilly v. Morse, 56 U.S. 62 (1853), the famous inventor of the single-line telegraph (Morse) claimed patent rights to the use of electro-magnetism for transmitting a signal–without limit to any “specific machinery or parts.” Id. The Supreme Court found the claim “too broad and covers too much ground.” Although Morse’s claim directed to a single functionally described element was deemed improper, patent attorneys quickly learned that a combination of functionally-claimed elements could work. An example of this is famously seen in the Wright Brothers early aircraft patents. See US821393.

The Supreme Court pushed-back again on functional claims–perhaps most notably in Halliburton Oil Well Cementing Co. v. Walker, 329 U.S. 1 (1946). In Halliburton, the Supreme Court invalidated Walker’s means-plus-function claims as indefinite after holding that it was improper to claim an invention’s “most crucial element … in terms of what it will do rather than in terms of its own physical characteristics or its arrangement in the new combination apparatus.” Id. Halliburton can be read as distinguishing between, on the one hand, claim elements that were already well known in the art, and on the other hand entirely new elements. Well-known functionality will be understood by those skilled in the art as translating to particular machinery or processes. And, the existence of prior art means that the patent doctrines of obviousness and anticipation will limit unduly broad scope. On the other hand, newly invented functionality has the potential of resulting in quite broad scope if divorced from the underlying mechanisms of operation. The Halliburton decision was not a surprise given that the Supreme Court had already repeatedly criticized functional claims. A good example of that criticism is seen in the 1938 General Electric decision where the court complained about the “vice” of functional claim limitations:

But the vice of a functional claim exists not only when a claim is ‘wholly’ functional, if that is ever true, but also when the inventor is painstaking when he recites what has already been seen, and then uses conveniently functional language at the exact point of novelty.

Gen. Electric Co. v. Wabash Appliance Corp., 304 U.S. 364, 371 (1938).

Halliburton did not stand for long. Rather, the Patent Act of 1952 was expressly designed to overrule Halliburton and revive the use of means-plus-function claims. The new law, now codified in 35 U.S.C. § 112(b) reads as follows:

(f) ELEMENT IN CLAIM FOR A COMBINATION.—An element in a claim for a combination may be expressed as a means or step for performing a specified function without the recital of structure, material, or acts in support thereof, and such claim shall be construed to cover the corresponding structure, material, or acts described in the specification and equivalents thereof.

Id. You’ll note that the statute does not suggest any difference between well-known or novel elements in their use of means-plus-function language. One key feature of Section 112(f) is its particularly narrow interpretive scope. Means-plus-function elements are not interpreted as extending to the full scope suggested by their broad claim language. Rather, as the statute recites, the scope is “construed to cover the corresponding structure, material, or acts described in the specification and equivalents thereof.” Id. Thus, a claim directed toward a “fastening means” appears quite broad on its face as covering all conceivable ways of fastening, but the term would likely be quite narrowly interpreted if the patent specification is also narrowly drafted. If the specification disclosed a “nail” as its only example, the court would likely limit “fastening means” to only include nails and their equivalents. Id. (“structure … described in the specification and equivalents thereof.”).

Invalid as Indefinite: Section 112(f) does not tell a court what to do in cases where the specification lacks disclosure of any “corresponding structure.” The Federal Circuit’s approach is to hold those claims invalid as indefinite under 35 U.S.C. § 112(b). In re Donaldson Co., 16 F.3d 1189 (Fed.Cir.1994) (en banc). Indefiniteness was also the hook used by the Supreme Court in Halliburton, then codified within Rev. Stat. § 4888. I am fairly confident that the Supreme Court would affirm the Donaldson precedent if it ever heard such a case. But, as discussed below, this interpretation leads to some seemingly unjust results.

Structure Plus Function: Because of the narrow construction and indefiniteness concern, patent drafters today largely shy-away from using means-plus-function claim language. Still, functional limitations offer powerful exclusive rights if given their full scope. In the marketplace, consumers ordinarily care more about whether a machine serves its appointed function rather than how it particularly works. A common approach for many skilled patent attorneys is to take advantage of functional limitations while still endeavoring to avoid being categorized as Section 112(f) means-plus-function limitations. This approach is often quite natural as the English language regularly identifies machines and parts by their function: a brake, a processor, a seat. These terms are inherently functional but are also tied to known mechanical structures. I call this approach “structure plus function” and it requires a threshold amount of structure sufficient to ensure that the limitation is not MPF. Structure-plus-function regularly results in broader claims than MPF and claims that that are less likely to be invalidated as indefinite. Again, this is nothing new, and they exact type of language discussed by the Supreme Court in its 1938 GE decision. Still, in recent cases the Federal Circuit has been more aggressively putting claims in the Section 112(f) MPF box. The key case on point is Williamson v. Citrix Online, LLC, 792 F.3d 1339 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (en banc).

The MPF rules are particularly pernicious in situations where the claim element at issue is already widely available in various forms. Since it is already widely available, the inventors (and their patent attorneys) typically feel less need to fully describe and specify particular examples of the well-known element. That inventor “feeling” is generally supported by strong precedent that a thin specification is appropriate for elements of the invention already known to the public. This well-known-element situation is also outside of the point-of-novelty policy concerns raised by Halliburtan. So, ordinarily, well known elements need only a thin disclosure within the specification. An off the shelf-component might not receive any structural disclosure at all other than identifying its name and how it connects-in with the rest of the invention. BUT, that all changes if the claim element is interpreted as MPF. If its MPF, the claim scope is limited only to what is disclosed (and equivalents), and a specification without structural disclosure will render the MPF claim invalid as indefinite. Thus, we have two entirely different drafting approaches that will depend greatly on how the claim is interpreted. And, following Williamson there is no longer a strong MPF interpretive presumption based upon the presence/absence of traditional MPF language such as “means for.” What that means practically is that the threshold is high-stakes, but unpredictable.

Recently, the Federal Circuit decided two Section 112(f) cases that push back a bit on Williamson:

- Dyfan, LLC v. Target Corp., — 4th —, 2022 WL 870209 (Fed. Cir. Mar. 24, 2022) (“code”, “application” and “system”); and

- VDPP LLC, v. Vizio, Inc., 2022 WL 885771 (Fed. Cir. Mar. 25, 2022) (non-precedential) (“storage” and “processor”).

None of the claim elements at issue in the cases used the word “means” as a signal of intent. Still, the two district courts interpreted the limitations as written in means-plus-function form. In addition, both district courts concluded that the claims were invalid as indefinite since the specifications lacked disclosure of corresponding structure.

The first step in 112(f) analysis is to determine whether a claim element should be classified as a means-plus-function claim. The most obvious clue is whether the element is written in traditional means-plus-function style–using the word “means” and also including some functional purpose. An element that does not use “means” is presumptively not a means-plus-function claim. However, that presumption is not longer a strong presumption. Williamson v. Citrix Online, LLC, 792 F.3d 1339 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (en banc). And, the presumption can be overcome by a showing that the claim “fails to recite sufficiently definite structure or else recites function without reciting sufficient structure for performing that function.” Id. (internal quotation marks removed). In addition, “nonce words” are seen as effectively using the word “means.” Id. Taking all this together, we know that Williamson is a quite important decision. It (1) moved away from a strong presumption against MPF interpretation absent “means” language and (2) established the “nonce word” doctrine. Not surprisingly, the case is the most-cited Federal Circuit decision of 2015. Still, some members of the court appear to see Williamson as potentially going too far, and that can be seen in the Dyfan and VDPP decisions by Judges Lourie (in both); Dyk, Stoll, Newman, and Taranto.

Claim Construction: The question of whether a claim element is in means-plus-function form is part of claim construction. It is thus the role of the court (rather than a jury) to decide and is ordinarily seen as a question of law with de novo review on appeal. One exception to this is comes when a party presents evidence leading to underlying factual conclusions. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. v. Sandoz, Inc., 574 U.S. 318 (2015). Those factual conclusions are given deference on appeal. Id. In some cases, the factual conclusions may conceivably so intertwine with the legal conclusions that the ultimate claim construction should also be treated as a mixed-question of law and fact and thus given deference on appeal. (This last sentence should be seen as my speculation on the correct rule rather than black-letter caselaw.)

In most situations, claim construction is purely a question of law and comes-in most commonly when the parties are endeavoring to show the level of understanding of a person of skill in the art (POSA). For MPF interpretation, this type of expert factual evidence appears to be more common than ordinary claim construction as the parties endeavor to show that a particular claim element would be understood as connoting “structure.” See Zeroclick, LLC v. Apple Inc., 891 F.3d 1003 (Fed. Cir. 2018).

Dyfan’s patents are directed to location-based triggers in mobile phones. Coincidentally, I used my idea of this technology in my internet law course recently in our discussion of privacy law–imagining Ads pop-ups based upon a user’s particular micro-location. In our example here, imagine that as you walk near the vacuum cleaner aisle of Target, your phone receives a “targeted” vacuum cleaner advert or coupon.

The Dyfan claim is directed to a “system” and requires “code” to cause a mobile device to output “visual information” based upon “location-relevant information.” The claim’s “wherein” clause requires certain timing of the outputs (automatic output of visual information after receiving a communication receipt but without requiring a separate “first message”). The wherein clause ties itself to the “system” (“wherein the system is configured…”) and does not state if the action is also done by the code. Thus, the courts identified this clause as the “system” element.

The district court found these two claimed elements to lack “structure” and therefore interpreted them as MPF elements. At step two, district court examined the disclosure documents found no corresponding structure within the specification. The result then is that the Code and System elements were un-construable and the entire claim invalid as indefinite.

On appeal, the Federal Circuit reversed and remanded–holding that the district court had improperly shifted the burden to the patentee to prove that the elements were not MPF. This presumption of no-MPF exists because the claims did not use the term “means.” In its decision, the appellate court began in an odd way by stating that overcoming the presumption requires “a preponderance of the evidence.” I call this ‘odd’ because preponderance of the evidence is the standard used for questions of fact rather than questions of law. As I mentioned, claim construction has been repeatedly deemed a question of law except for limited circumstances. Here though, there was expert testimony that those skilled in the art would understand “code” to be a particular term of art that encompasses a computer program, and that “off-the-shelf-software” was available to perform the specific function claimed. On appeal, the Federal Circuit began with a presumption that the code was not-MPF, and that presumption was further solidified by the unrebutted testimony indicating structure. As part of this, the appellate panel also rejected the notion that the code limitation was “purely functional.”

The system limitation is a bit more complicated — certainly the “system” has structure. The claim actually requires that the system include a physical building. But, the claim also requires that the system be “configured such that” messages are sent in a particular order and based upon particular triggers. “A system comprising . . . wherein the system is configured such that . . . .” Section 112 speaks in terms of an “element”, and the court was faced with the question of whether (1) the system itself is the element, or instead (2) the element is the sub-part of the system that performs the claimed function. On appeal, the Federal Circuit did not decide this question, but instead held that the claims provide sufficient structure either way. The court particularly noted that the aforementioned ‘code’ is part of the system and it it is pretty clear that the code would be doing the work here as well.

Although the wherein clause does not expressly refer to the previously recited “code,” it references specific functions that are defined or introduced in the code limitations and thus demonstrates that it is the code that performs the function recited in the wherein clause.

Slip Op. Since these claim elements included sufficient structure, the appellate panel concluded that they were not written in means-plus-function form. And, as a consequence the indefiniteness ruling

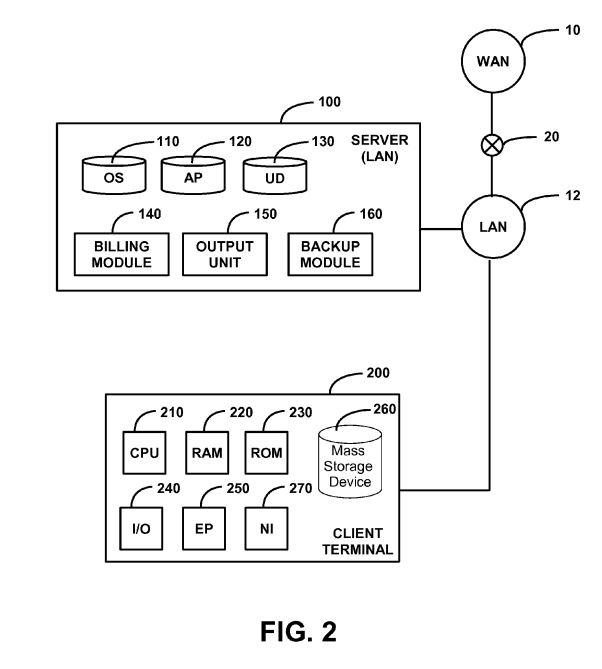

VDPP is non-precedential, but reaches the same results. And, although decided only one-day after Dyfan, it favorably cites that decision and particularly the shifting of burdens and evidentiary requirements. VDPP’s patents relate to technology for blending 2-D video streams so that they appear 3-D. US9699444B2 claim 1 is directed to “an apparatus” having two elements: (1) a storage and (2) a processor. The storage is “adapted to store one or more frames.” The processor has a number of claimed functions, including obtaining and expanding an image; creating a ‘bridge frame’ that is a “non-solid color”; and blending various frames for display. The patent has a 2001 priority date, and the claims here have shifted substantially to capture market development.

The C.D.Cal. district court determined that VDPP’s claimed “processor” and “storage” elements were both subject to § 112(f) since they “do not describe how to carry out the recited functions—only that they do” somehow accomplish those functions. That statement appears almost lifted from Halliburton’s definition of means-plus-function claiming. In another pithy restatement of its conclusions, the district court also identified each term as a “black box for performance of a function.” On appeal the Federal Circuit reversed–holding that the “processor” and “storage” elements contained sufficient structure.

In the case, the district court “summarily concluded that the limitations [were] subject to § 112(f).” On appeal, the Federal Circuit found that erroneous because claims without the “means” term are presumed to not be MPF. This issue here seems to get to the heart of the nonce-word debate. My understanding of ‘nonce words’ is that they are presumed to be MPF triggers. Thus, the district court’s opinion appears to be based on its conclusion that the processor and storage are “nothing more than

nonce words.” On appeal, however, the Federal Circuit took a different path. Rather than starting with the nonce work question, the court began with the presumption of no-MPF absent the word “means.” The court then quoted Dyfan’s statement that overcoming the presumption requires evidence.

Vizio was required to provide at least some evidence that a person of ordinary skill

would not have understood the limitations to ‘recite sufficiently definite structure[s].’

Slip Op. (quoting Dyfan). The district court had avoided this presumption by identifying the terms as nonce words. That approach was apparently wrong: “The court pointed to no such evidence from Vizio, instead summarily concluding that the limitations are subject to § 112(f). . . That is insufficient to overcome the presumption

against application of § 112(f).” Perhaps the best way to reconcile the developed doctrine here is that a district court should not identify a word as a ‘nonce’ word based upon reasoning alone. Rather, that determination requires some sort of evidence. In VDPP, the court again referred back to Dyfan and shows district courts how to cite the case:

Vizio’s arguments are particularly unpersuasive in view of our holding in Dyfan. In Dyfan, the district court determined that the limitations “code” and “application” were subject to 112(f).

We reversed the district court’s construction of those terms (among others), explaining that the court did not give effect to the presumption against § 112(f). More specifically, we held that the defendant failed to show “that persons of ordinary skill in the art would not have understood the ‘code’/‘application’ limitations to connote structure in light of the claim as a whole.” That same rationale applies here. As explained above, the court ignored that it was Vizio’s burden to rebut the presumption against § 112(f), and Vizio failed to meet that burden.

Slip Op. I’ll just note that this type of talk of ‘presumption’ and presumably external ‘evidence’ is radically different from how the court usually discusses claim construction. Rather, claim construction is a question of law where we are searching for the proper construction. Typically neither party has a burden of proving a question of law.

In VDPP, the district court also pointed to evidence presented that the storage and processor are known structural forms. The patentee had fallen into the pernicious trap noted above by explaining in the specification that that “processors” and “storage” are “well-known” in the art. Here, the court concluded that the specification statement that these are “well known” provides good evidence that the terms were not intended as MPF (without further elaboration or explanation of the reasoning here).

The one problem with the court’s analysis in VDPP is that it implicitly concludes that the “processor” counts as the “element” for MPF analysis. But, the claim is directed to a particular function, not simply a “processor for processing.” Here, for instance, the claim requires “a processor adapted to: obtain a first image frame from a

first video stream; ….” Although a general processor may be well known, a processor “adapted” as claimed was not well known in the art, and the question that the court needs to ask with regard to structure is whether the claim itself provides the structure for performing the recited function.

As you can see, this area is ripe with historical confusion, statutory bright lines, and shifting precedent. I expect that the court will continue to develop precedent, but I expect that this pair of cases will begin to tone-down the impact of Williamson while also shifting litigation tactics.