2019

Lilly v. UroPep

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

PTO Guidance: Bridging the Swamp

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

2019 Iowa Law Review Issue: Administering Patent Law

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

USPTO Eligibility Examination Practice

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Trademark Filing Issues

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Donald R. Dunner (1931-2019)

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Off-Topic Chart of the Day from Google’s N-Gram Viewer

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Campbell’s Imaginary-Tiny-Cans Fail to Invalidate

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Georgia v. Public Resource: Twenty-five centuries of history reject the foundation of Petitioners’ case

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Columbus Day

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Patently-O Bits and Bytes by Juvan Bonni

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Then and Now: 1800’s Supreme Court Patent Cases

by Dennis Crouch

In this new series, I'm looking back to 19th Century Supreme Court patent cases; looking for their wisdom; and considering their ongoing importance.

Winans v. Denmead, 56 U.S. 330 (1853) is cited as an early doctrine of equivalents (DOE) case, although I see it also as an early claim construction decision. According to Westlaw, is the 10th most cited patent case of the 19th Century. At the time of the case, Winans was on his way to becoming one of the wealthiest Americans by making and selling railroad equipment.

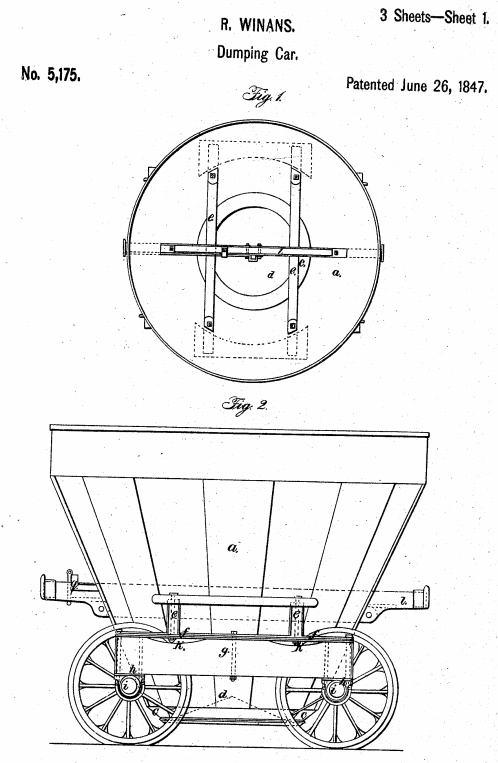

As shown in the diagram below, the Winans patent covers a railroad car for transporting coal, etc. The car has a cone-shape particularly "the form of a frustum of a cone, substantially as herein described" The shape allowed the car to carry "more coal in proportion to its own weight than any car previously in use." Further, excess load did not distort the shape because it "presses equally in all directions." Id.

The accused infringer inspected a Winans-made car and then made its own -- although using an octagonal shape rather than circular as in the patent (looking down as in fig 1). The defendants argued this difference in should have resulted in a non-infringement verdict; Winans argued that this difference was immaterial because the octagonal car was almost the same shape and obtained the same useful results. Further, after being used for a while, the sheet metal used will shape itself into a circle.

The jury was asked Winans asked for jury instructions akin to the function-way-result test:

whether 'the form adopted by the defendants accomplished the same result, substantially, with that in view of the plaintiff, and upon substantially the same principle and in the same mode of operation.’

However the lower court took a much narrow stance and effectively instructed the jury that they could only find infringement against conical bodies since the operation of the invention is "due alone to conical vehicles and not to rectilinear bodies." With that narrow instruction, the jury could not find infringement.

The Supreme Court reversed course -- concluding that the court must not allow form to dictate substance.

[I]t is the duty of courts and juries to look through the form for the substance of the invention—for that which entitled the inventor to his patent, and which the patent was designed to secure; where that is found, there is an infringement; and it is not a defence, that it is embodied in a form not described, and in terms claimed by the patentee. . . .

The exclusive right to the thing patented is not secured, if the public are at liberty to make substantial copies of it, varying its form or proportions.

In the end, however, I see this case largely about claim construction. The Supreme Court explained that a cone in Euclidean sense is impossible to construct except by imagination.

It may safely be assumed, that neither the patentee nor any other constructer has made, or will make, a car exactly circular. In practice, deviations from a true circle will always occur.

Thus, it is clear to the court that the "cone" limitation in the claim does not require an exact cone. The court went on to interpret the meaning of the patent as covering a design

"so near to a true circle as substantially to embody the patentee's mode of operation, and thereby attain the same kind of result as was reached by his invention. . . . It must be the same in kind, and effected by the employment of his mode of operation in substance."

The court ordered that on remand the jury can consider infringement under this broader view of the patent.

Justice Curtis wrote the 5-4 majority opinion.

The dissent by Justice Campbell began with a suggestion that the substance of the invention is likely obvious (lack of invention).

The merit of the plaintiff seems to consist in the perfection of his design, and his clear statement of the scientific principle it contains. . . . There arises in my mind a strong if not insuperable objection to the admission of the claim, in the patent for ‘the conical form,’ or the form of the frustum of a cone,' as an invention.

The dissent went on - assuming that the patent is valid -- noted that it should be assumed that a patentee will draft claims in a way that reach "exactly the limits of his invention" and that it is improper for the court to "extend, by construction, the scope and operation of his patent, to embrace every form which in practice will yield a result substantially equal or approximate to his own."

The plaintiff confines his claim to the use of the conical form, and excludes from his specification any allusion to any other. He must have done so advisedly. He might have been unwilling to expose the validity of his patent, by the assertion of a right to any other. Can he abandon the ground of his patent, and ask now, for the exclusive use of all cars which, by experiment, shall be found to yield the advantages which he anticipated for conical cars only?

The dissent went on to complain that the majority's approach has little bound --

The claim of today is, that an octagonal car is an infringement of this patent. Will this be the limit to that claim? Who can tell the bounds within which the mechanical industry of the country may freely exert itself? What restraints does this patent impose in this branch of mechanic art?

The patentee is obliged, by law, to describe his invention, in such full, clear, and exact terms, that from the description, the invention may be constructed and used. Its principle and modes of operation must be explained; and the invention shall particularly ‘specify and point’ out what he claims as his invention. ... Nothing, in the administration of this law, will be more mischievous, more productive of oppressive and costly litigation, of exorbitant and unjust pretensions and vexations demands, more injurious to labor, than a relaxation of these wise and salutary requisitions of the act of Congress. In my judgment, the principles of legal interpretation, as well as the public interest, require, that this language of this statute shall have its full significance and import.

Id.

In Graver Tank, the Supreme Court identified Winans as the origin of the doctrine of equivalents.

The essence of the doctrine is that one may not practice a fraud on a patent. Originating almost a century ago in the case of Winans v. Denmead, 15 How. 330, 14 L.Ed. 717, it has been consistently applied by this Court and the lower federal courts, and continues today ready and available for utilization when the proper circumstances for its application arise.

Graver Tank & Mfg. Co. v. Linde Air Products Co., 339 U.S. 605, 608 (1950).

Still, when I read the case, I see claim construction. Notably, the question presented by the court is whether the word 'cone' is properly construed and the court answered that it is nearly a circle, and the purpose of the invention helps to understand the limit of that subjective limitation.

In our judgment, the only answer that can be given to these questions is, that it must be so near to a true circle as substantially to embody the patentee's mode of operation, and thereby attain the same kind of result as was reached by his invention.

Id. The reason the court felt obliged to consider this construction is its conclusion that "construing the letters-patent" "is a question of law, to be determined by the court." The dissent seemed to similarly agree that the focus is about claim construction -- arguing that the majority's "construction" is too broad.

= = =

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Executive Orders on Agency Practice

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

IPWatchdog turns 20

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Facebook is Prevailing Party Even Though Case Dismissed as Moot

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Supreme Court 2019-2020: Introduction to the Term’s Patent Cases

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

My Take after Oral Arguments: Supreme Court Likely to Affirm in Peter v. NantKwest

by Dennis Crouch

Peter v. NantKwest (Supreme Court 2019) [TRANSCRIPT]

The Supreme Court heard oral arguments on October 7, 2019 in this case involving the question of attorney fees in Section 145 civil actions. I'll agree with Mark Walsh who identified this as a "a dry, procedural patent case." But, I really enjoyed the oral arguments -- Read some of the drama below.

Before getting too dramatic: I recognize that the result of this case is basically not going to have much of any impact on patent cases. So, perhaps one benefit is that the court is unlikely to ruin the patent system with its decision here. Depending upon the outcome, Section 145 civil actions will be seen as relatively more/less expensive for the applicant. But, they are already very expensive for an applicant to pay its own expenses. My take is that the added PTO-attorney expense will be a relatively small extension of the already high-costs assuming that the PTO continues to be fairly thrifty in its defense of these cases. On the PTO side, the agency has to pay its attorneys from collected fees somehow. If it doesn't get the fees from the 145 challenger, then it will collect them from the applicant pool in general (about $1.60 per applicant) as it has done for many years.

Conventional wisdom in patent cases is reversal. The Supreme Court does not take cases to offer congratulations to the lower court. And the absence of circuit splits means that there isn't a right vs wrong appellate court. My read of the oral argument though goes against this conventional wisdom -- I'm betting on affirmance. The Gov't dropped its argument that the American Rule does not apply; and so the American Rule as applied in other areas has the potential of being undermined by a Gov't win here.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

DISTORTED DRUG PATENTS

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Patently-O Bits and Bytes by Juvan Bonni

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.