The UK Supreme Court’s Re-interpretation of FRAND in Unwired Planet v. Huawei

Guest post by University of Utah College of Law Professor Jorge L. Contreras.

In its Judgment of 26 August 2020, [2020] UKSC 37, the UK Supreme Court affirms the lower court decisions ([2017] EWHC 711 (Pat) and [2019] EWCA Civ 38) in the related cases Unwired Planet v. Huawei and ZTE v. Conversant [I discuss the High Court’s 2017 decision here]. The judgment largely favors the patent holders, and holds that a UK court may enjoin the sale of infringing products that incorporate an industry standard if the parties do not enter into a global license for patents covering that standard. The court covers a lot of important ground, including the parties’ compliance with EU competition law under Huawei v. ZTE (CJEU, C-170/13, 2015) (¶¶ 128-158) and the appropriateness of injunctive remedies under UK law (¶¶ 159-169). But in this post, I will focus on what I consider to be the most significant aspect of the court’s judgment – its interpretation of the patent policy of the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI), an interpretation that largely determines the outcome of the case and could have far-reaching ramifications for the technology sector.

Background

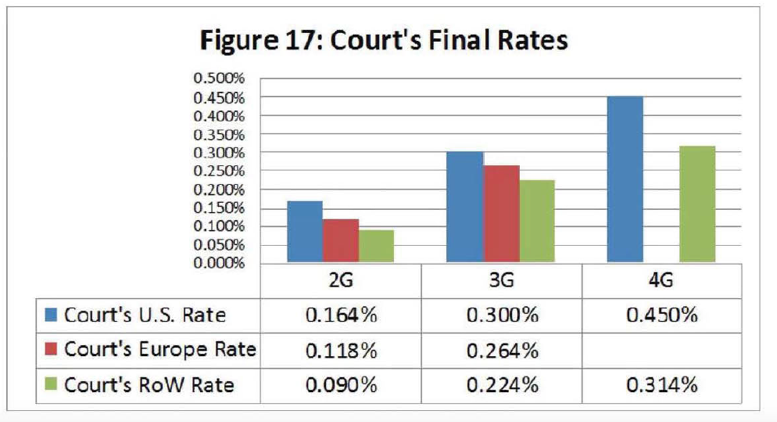

The case began in 2014 when Unwired Planet, a U.S.-based patent assertion entity (PAE), sued Huawei and other smartphone manufacturers for infringing UK patents that it acquired from Ericsson (other suits were brought elsewhere). The patents were declared essential to the 2G, 3G and 4G wireless telecommunications standards developed under the auspices of ETSI, an international standards-setting organization (SSO). A companion case was brought by another PAE, Conversant, with respect to similar patents that it acquired from Nokia.

Because Ericsson and Nokia participated in standards-development through ETSI, they were bound by ETSI’s various policies, including its patent policy. Accordingly, when the patents were acquired by Unwired Planet and Conversant, these policies continued to apply. The ETSI patent policy requires that ETSI participants that hold patents that are essential to the implementation of ETSI standards (standards-essential patents or SEPs) must license them to implementers of the standards (e.g., smartphone manufacturers) on terms that are “fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory” (FRAND).

Huawei and ZTE are China-based smartphone manufacturers with operations in the UK. Unwired Planet and Conversant offered to license the patents to them on a worldwide basis, but the manufacturers objected to their proposed royalty rates, claiming that they were not FRAND. Among other things, Huawei argued that any license entered to settle the UK litigation should cover only UK patents. After numerous preliminary proceedings, in 2017 the UK High Court (Patents) held that a FRAND license between large multinational companies is necessarily a worldwide license. Moreover, if Huawei did not agree to such a worldwide license incorporating FRAND royalty rates determined by the court, the court would enter an injunction against Huawei’s sale of infringing products in the UK. The Court of Appeal largely affirmed the High Court’s ruling.

The UK Supreme Court Embraces SSO Policy Interpretation

In its judgment, the UK Supreme Court gives significant weight to the language and intent of the ETSI patent policy – far more than either the High Court of the Court of Appeal. This approach contrasts starkly with that of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, which decided another FRAND case, FTC v. Qualcomm (9th Cir., Aug. 11, 2020), just a fortnight earlier. The Ninth Circuit explicitly dodged any interpretation of the SSO policies at issue in that case (those of the Telecommunications Industry Association (TIA) and Alliance for Telecommunications Industry Solutions (ATIS)), focusing solely on the antitrust issues raised by the parties. The UK Supreme Court, in contrast, appears to have embraced the exercise of SSO policy interpretation, focusing intently on the language and drafting history of the ETSI policy, as well as its own conclusions about the intent of that language. This judicial interpretive exercise leads to three key holdings in the case:

ETSI’s Policy Compels a Worldwide License

In determining that a FRAND license between Unwired Planet and Huawei should be global in scope, rather than limited to the UK, Mr Justice Birss of the UK High Court looked to industry practice and custom. He first noted that “the vast majority” of SEP licenses in the industry, including all of the comparable licenses introduced at trial, were granted on a worldwide basis, and both Unwired Planet and Huawei are global companies. He then reasoned that “a licensor and licensee acting reasonably and on a willing basis would agree on a worldwide licence” (¶543). In contrast, he regarded the prospect of two large multinational companies licensing SEPs on a country-by-country basis to be “madness” (¶543). Accordingly, the High Court held that a FRAND license, under these circumstances, must be a worldwide license.

The UK Supreme Court acknowledges the industry practices referenced by the High Court, but bases its reasoning much more heavily on ETSI’s patent policy. First the Supreme Court recognizes the inherent territorial limitations on the jurisdiction of national courts (¶58). However, it is the ETSI patent policy, adopted by the SSO and accepted by its participants, that opens the door both to the consideration of industry practices (¶61) and the extension of national court jurisdiction to the determination of global royalty rates. The Court concludes, “[i]t is the contractual arrangement which ETSI has created in its patent policy which gives the [English] court jurisdiction to determine a FRAND licence” for a multi-national patent portfolio (¶58). Thus, the Supreme Court affirms the decisions of the lower courts, but grounds its decision more firmly in the ETSI patent policy.

ETSI’s Policy Contemplates Injunctions

The Supreme Court also relies on the ETSI patent policy to support its conclusion that SEP holders may seek injunctions against standards implementers who do not enter into FRAND license agreements. The availability of injunctions in FRAND cases has been the subject of considerable debate in jurisdictions around the world. The UK court comes down in favor of allowing such injunctions, not on the ground that patent holders can do whatever they like, but because “[t]he possibility of the grant of an injunction by a national court is a necessary component of the balance which the [patent] policy seeks to strike, in that it is this which ensures that an implementer has a strong incentive to negotiate and accept FRAND terms for use of the owner’s SEP portfolio” (¶61).

This conclusion is striking in two regards. First, it largely omits the analysis of EU competition law that typically accompanies the consideration of injunctive relief in EU FRAND cases. While the Court later discusses Huawei v. ZTE at length (¶¶ 128-158), it does so while analyzing whether the parties violated applicable competition law, not whether competition law itself establishes a basis for seeking injunctive relief.

Second, and more surprisingly, the Court imputes to the ETSI patent policy an affirmative authorization to seek injunctive relief that is found nowhere in the policy itself. From the fact that the patent policy includes provisions that are favorable to both implementers and SEP holders, the Court finds that the policy intended to establish a “balance” between these two groups, and that a “necessary component” of that balance is the ability of the SEP holder to seek an injunction against the implementer.

This is a surprising result that was not forecast in either of the decisions below. It is particularly significant because it may influence other courts’ interpretations of the ETSI patent policy. It may also encourage other SSOs, if not ETSI itself, to adopt policy language expressly prohibiting participants from seeking injunctive relief against adopters of their standards (as IEEE has already done).

Non-Discrimination is Not a Stand-Alone Commitment

The third significant aspect of the judgment relates to the non-discrimination (-ND) prong of the ETSI FRAND commitment. At the High Court, Mr Justice Birss held that the -ND part of a FRAND commitment does not have a “hard edge”, which would mandate that every FRAND license must be priced at exactly the same rate. Instead, based on EU competition law, he found that differences in pricing should not be objectionable unless they distort competition. As such, he did not fault Unwired Planet for pricing some FRAND licenses below the rates that it offered to Huawei.

I disagreed with Justice Birss’s reasoning on this point in 2017, arguing that it “conflate[s] two issues: the competition law effects of violating a FRAND commitment, and the private “contractual” meaning of the FRAND commitment itself.” I was thus pleased to see that the UK Supreme Court looks not to competition law, but to the content of the ETSI patent policy, to define the scope of the SEP holders’ non-discrimination obligation.

This being said, the Court’s interpretation of “non-discrimination” is novel and somewhat radical. Rather than considering the -ND prong of FRAND to be an independent commitment of the SEP holder – that the licenses it grants not discriminate (however that is defined) — the Court blends the -ND prong together with the “fair and reasonable” (FRA-) prong to form a “general” obligation. It explains,

Licence terms should be made available which are ‘fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory’, reading that phrase as a composite whole. There are not two distinct obligations, that the licence terms should be fair and reasonable and also, separately, that they should be non-discriminatory. Still less are there three distinct obligations, that the licence terms should be fair and, separately, reasonable and, separately, non-discriminatory” (¶113 (emphasis added)).

As evidence for its interpretation, the Court points to ETSI’s rejection, in 1993, of a ‘most-favored license’ clause in its patent policy. Interpreting the policy’s non-discrimination commitment as a ‘hard edged’ commitment would, in the Court’s view, re-introduce most-favored treatment “by the back door” (¶116). As a result, the Court concludes that the non-discrimination prong of ETSI’s FRAND commitment merely “gives colour to the whole and provides significant guidance as to its meaning. It provides focus and narrows down the scope for argument about what might count as ‘fair’ or ‘reasonable’ for these purposes in a given context” (¶114).

As far as I am aware, the elimination of non-discrimination as a separate pillar of the FRAND obligation is at odds with both U.S. case law and the academic literature that address this issue (an overview can be found here). The Court’s reasoning also contradicts the explicit concerns of the European Commission, which emphasized the importance of non-discrimination during debates over the ETSI patent policy in 1992:

Terms and conditions applied to participants and non-participants should not significantly discriminate against the latter. A fortiori where the standard-making body acts in an official or quasi-official standard-making capacity and where its standards are recognized and even made compulsory by virtue of legislation, access to the standard must be available to all without a precondition of membership of any organization (Communication from the Comm’n, Intellectual Property Rights and Standardization at p. 19, 27 Oct. 1992).

Clearly, the Commission did not view non-discrimination simply as giving color to the meaning of ‘fair and reasonable’. On the contrary, non-discrimination, standing alone, is among the most important features of the FRAND commitment. The UK Supreme Court’s interpretation to the contrary is thus highly problematic.

Conclusions

While I applaud the UK Supreme Court’s shift from a focus on competition law to the language and intent of the ETSI patent policy, I am concerned about its conclusions regarding the authority of one country’s courts to determine global FRAND rates, the availability of injunctive relief against standards implementers and the demotion of non-discrimination as an independent prong of the FRAND analysis.

One silver lining in this cloud, perhaps, is that the Court’s judgment, which relies so heavily on the particulars of the ETSI policy, is thus limited to the ETSI policy. It is unclear how much weight its findings would have for a court, whether in the UK or elsewhere, assessing participants’ obligations under FRAND policies adopted by different SSOs such as TIA and ATIS (as in FTC v. Qualcomm), not to mention SSOs such as IEEE that have adopted language expressly contravening some of the interpretations that the Court makes with respect to ETSI.

In fact, the Court seems to invite SSOs to re-evaluate their patent policies. Huawei objected to the UK court’s determination of global FRAND rates because, among other things, permitting a national court to resolve a global dispute could promote “forum shopping, conflicting judgments and applications for anti-suit injunctions” (¶90). The Court tacitly agrees, but then pushes back, seeming to blame SSOs for allowing this to happen:

“In so far as that is so, it is the result of the policies of the SSOs which various industries have established, which limit the national rights of a SEP owner if an implementer agrees to take a FRAND licence. Those policies … do not provide for any international tribunal or forum to determine the terms of such licences. Absent such a tribunal it falls to national courts, before which the infringement of a national patent is asserted, to determine the terms of a FRAND licence. The participants in the relevant industry … can devise methods by which the terms of a FRAND licence may be settled, either by amending the terms of the policies of the relevant SSOs to provide for an international tribunal or by identifying respected national IP courts or tribunals to which they agree to refer such a determination” (¶90).

In this regard, I wholeheartedly agree with the Court. I have long advocated the creation of an international rate-setting tribunal for the determination of FRAND royalty rates. I continue to believe that such a tribunal, if supported by leading SSOs, would eliminate much of the inter-jurisdictional competition and duplicative litigation that currently burdens the market. If the UK Supreme Court’s judgment in Unwired Planet encourages ETSI and other SSOs to endorse such an approach, then this could be the most significant outcome of the case.