The Reverse Doctrine of Equivalents: An “Anachronistic Exception” Lives Another Day

by Dennis Crouch

I have been following the Steuben Foods appeal for the past year - thinking that it may be the case where the Federal Circuit nails in the coffin on the reverse doctrine of equivalents. The new decision ultimately left this question open, but it provides a fascinating exploration of three distinct doctrines of equivalence in patent law:

- The Reverse Doctrine of Equivalents (RDOE): This centuries-old defense, originating from the Supreme Court's 1898 Boyden Power-Brake decision, allows an accused infringer to escape liability even when their device falls within the literal scope of the claims. A key question here was whether this doctrine even survived the 1952 Patent Act.

- The Doctrine of Equivalents (DOE): This traditional doctrine allows patent holders to prove infringement even when the accused device falls outside the literal scope of the claims. In this case, the court examined whether continuous sterilant addition could be equivalent to intermittent addition.

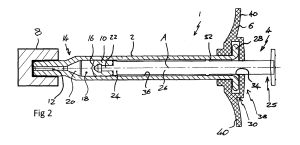

- Means-Plus-Function Equivalents: Under 35 U.S.C. § 112(f), means-plus-function claims cover not only the corresponding disclosed structure but also its equivalents. The court here analyzed whether rotary wheels could be equivalent to the disclosed conveyor structures.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.