by Dennis Crouch

I wrote an essay last month discussing the rarity of certified questions on appeal under 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b). See, Dennis Crouch, Certified Questions on Appeal under § 1292(b), Patently-O (January 31, 2020).

In Feit Electric Co. v. CFL Tech. (Fed. Cir. February 3, 2020)[20-110 CAFC denial], the Federal Circuit has denied Feit's petition for discretionary review of a certified question.

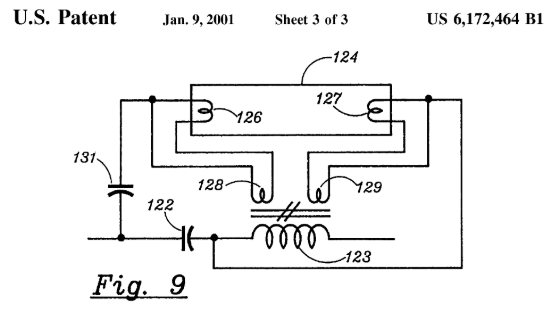

The case involves CFL Tech's U.S. Patent No. 6,172,464 that was previously held unenforceable (back when owned by Ole Nilssen). However, the unenforceability decision came before the law of unenforceability changed in Therasense, Inc. v. Becton, Dickinson & Co., 649 F.3d 1276 (Fed. Cir. 2011) (en banc). Therasense made it harder to find patent unenforceable. Thus, if re-judged under the revised law, the '464 patent might actually be enforceable.

Change of Law: Unenforceability of the patent has been fully litigated and decided and issue preclusion would normally apply. The certified question on appeal is whether the change-of-law exception to issue preclusion applies in this case - citing primarily Dow Chemical Co. v. Nova Chemicals Corp., 803 F.3d 620 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (finding that the Supreme Court's decision in Nautilus was an “intervening change in law”).

The CFL Tech district court applied the change-of-law doctrine under Dow and thus found no issue preclusion. However, the district court also noted the case of Morgan v. Dep’t of Energy, 424 F.3d 1271 (Fed. Cir. 2005). In Morgan, the Federal Circuit limited the change-of-law doctrine in cases involving "clarifying" interpretations. Uncertain in its opinion, the district court then certified the question for discretionary interlocutory appeal.

Discretion: Here, the appellate court used its discretion to not hear the appeal, but then went ahead to decide that the district court got it right -- no preclusion.

Feit and the amici read too much into Morgan. All that Morgan rejected was a version of the change-in-law exception “so broad” that it would deny preclusion based on judicial decisions that merely “clarify earlier interpretations of a statute.” It did not reject the higher standard for a result-altering intervening change in law required by Dow Chemical, which was applied in this case based on the significant change of law made by this court in Therasense.

Thus, although the Federal Circuit refused to hear the appeal, it went ahead and decided the issue.

Advisory Dicta: I would call the appellate decision advisory dicta -- and thus would not become "law of the case" since the court did not actually hear the appeal. However, from a practical standpoint the district court will (and should) follow the guidance laid down here. The Federal Circuit took the same approach in Heat Techs., Inc. v. Papierfabrik August Koehler Se, 2019 WL 3430477 (Fed. Cir. July 18, 2019) (denying petition for interlocutory appeal, but explaining its interpretation of the law in the denial order).