2020

When does a Logo Undermine a Design Patent Case?

This week in Property: Efficient Infringement

Patently-O Bits and Bytes by Juvan Bonni

Shooting from the Hip and Curing a Premature Appeal

Cancelling a Covenant-Not-To-Sue

Google v. Oracle: Amici Weigh in on Why the Supreme Court Should Reverse the Federal Circuit’s Rulings

“Nonappealable” means Not Keeping the PTAB in Check

Parallel District Court and ITC Litigation

A Decade of Federal Circuit Decisions

Certiorari Denied in Eligibility Cases

Patently-O Bits and Bytes by Juvan Bonni

Ladders of Abstractions: How Many Rungs Till the Threshold?

Opening a Closed Markush Group

En Banc: Power of Customs & Border Protection

Single-Point-Of-Novelty Innovations and the Obvious-To-Try Analysis

Patently-O Bits and Bytes by Juvan Bonni

Guest Post: Against the Design-Seizure Bill

By Sarah Burstein, Professor of Law at the University of Oklahoma College of Law

As previously covered here on Patently-O, a new design patent bill has been introduced in Congress. The so-called “Counterfeit Goods Seizure Act of 2019” would allow Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) to seize goods accused of design patent infringement.

This is a bad idea.

This bill is not reasonably tailored to address its purported goal of “stem[ming] the flow of counterfeit goods.” Instead, it will allow design patent owners to foist their private enforcement costs onto taxpayers, under circumstances that are unlikely to result in accurate determinations of infringement. Moreover, this type of ex parte, non-public system of adjudication is ripe for abuse.

I have three major groups of concerns about this bill: substantive, procedural, and rhetorical. This post will address them in turn.

Substantive concerns

First, CBP will not be in a position to make accurate determinations of design patent infringement.

The test for design patent infringement, as set forth by the en banc Federal Circuit in Egyptian Goddess v. Swisa, involves two steps. (For more on the Egyptian Goddess test, see this short essay.)

The first step requires a comparison of the claimed design (i.e., what’s illustrated in the patent) and the accused product. If those designs look plainly dissimilar, the test is over; there is no infringement. If the designs look like they might be the same, then the factfinder must consider the designs in light of the closest prior art.

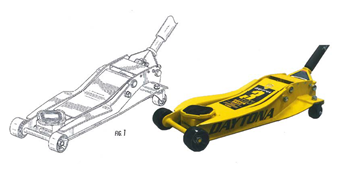

This second step is important. Often, two designs that look similar in the abstract look much less so when considered in light of the prior art. Consider this recently-litigated example. The patented design is shown below on the left; the accused design is below on the right:

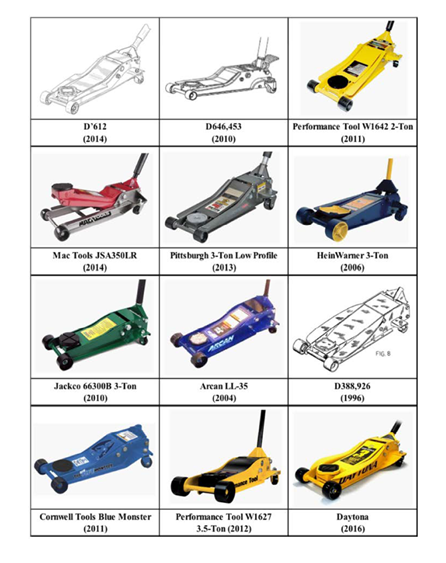

These two designs might not look plainly dissimilar in the abstract. But when viewed in light of the prior art, a number of visual differences become apparent:

Ultimately, the judge correctly concluded that the patent owner was not likely to prove infringement (though the path to that decision was a bit more circuitous).

How would this have turned out under the design-seizure bill? Who would have collected the closest prior art? There are many things to like about the Egyptian Goddess test, but one downside is that step two requires an informed and motivated defendant to work well. In an ex parte CBP proceeding, there is no one to play that role. CPB officials are not trained (and one assumes, lack the resources) to conduct their own prior art searches. And patent owners have zero incentives to provide any—let alone the closest—prior art when they record their patents or when they give CBP information about “suspect inbound shipments.” See generally 5 McCarthy on Trademarks § 29:37 (“Trademark owners that see a higher success rate in Customs seizures are typically the ones that continuously and vigilantly provide Customs with information to use in identifying suspect inbound shipments. Such information could include the names of known foreign counterfeiters, countries of origin, suspect importers, and the like.”)

If CBP skips (or lacks sufficient information to properly conduct) Egyptian Goddess step two, competing products could seized even when they don’t infringe. CBP could seize products that merely practice the prior art or that resemble the claimed design solely in functional aspects (for all but the most pioneering products, one would expect to find any truly functional elements in the prior art).

Thus, ex parte assessments of design patent infringement are likely to lead to significant over-enforcement. At least one other commentator has voiced similar concerns. Over-enforcement would chill legitimate competition and ultimately raise prices for consumers—the very consumers who would be footing the bill through their tax dollars.

In any case, it is simply not correct—as some proponents of this bill have asserted—that all CBP would have to do is look at the design patent and the accused product and see if they look the same.

Some might argue that CBP could review the prior art cited on a particular design patent. But that’s by no means guaranteed to be the closest prior art. Some of it may not even be available at the time of enforcement; USPTO examiners often cite web pages using basic URLs and link rot is a very real concern.

One proponent of this bill has asserted that “Customs officers have already effectively demonstrated the ability to determine whether imported goods infringe a design patent, through its ongoing enforcement of design-patent exclusion orders.” But how do we know that is true? What kinds of orders are being issued by the ITC? How broad (or narrow) are they? How can we know whether CBP is enforcing them well? While we can assume CBP does the best it can in the restraints under which it operates, any assertion about what that actually looks like in practice requires something more that ipse dixit before it can have any persuasive weight.

Procedural concerns

This bill raises also raises serious due process concerns. What recourse is there for competitors whose goods are improperly seized? What accountability is there for design patent owners who direct CBP officials to competing products that don’t actually infringe? Based on my experience reviewing design patent complaints, it appears that many attorneys are under the mistaken impression that design patents cover design concepts, when they really only cover the specifically-claimed designs. I call this “the concept fallacy.” It’s remarkably common in federal court filings. If members of the bar feel comfortable making such allegations in federal court, where they are subject to both judicial sanctions and public scrutiny, what allegations will they feel comfortable making to the CBP?

The non-public nature of these seizures is also a concern. How can we know how well the system is (or is not) working? Based on the information Professor Rebecca Tushnet has been able to gather about trademark seizures, it appears that the agency does not keep good records and its substantive determinations are guided by materials provided by trademark owners. One would assume that if the design-seizure bill were passed, groups like INTA, AIPLA, and/or IPO would be happy to provide their own guidelines for CBP. If that happens, any such materials should be made public, to ensure accuracy. (Hopefully, it won’t take a FOIA lawsuit like the one Professor Tushnet had to file.)

Rhetorical concerns

Finally, the entire framing of this bill is based on conflating design patent infringement with “counterfeiting.” Those two things are not the same.

“Counterfeiting” is a term of art in U.S. IP law. The Lanham Act defines a “counterfeit” as “a spurious mark which is identical with, or substantially indistinguishable from, a registered mark.” 15 U.S.C. § 1127.

Actual counterfeiting (i.e., as that term is defined in the Lanham Act) is arguably the worst type of IP infringement. But it’s already illegal. Indeed, it’s subject to criminal penalties.

If Congress thinks those remedies are not severe enough, it is free to increase them. But Congress should narrowly tailor any such efforts to acts that actually constitute counterfeiting. That’s not what’s going on here.

Proponents of this bill like to talk about “counterfeits without labels” (a strange concept in light of the relevant statutory definitions, but that’s an issue for another day) but the bill goes beyond anything that would seem to fall into that category.

Most design patents can be infringed by products that don’t replicate the entire appearance of the patent owner’s own product—if any. (Design patent owners, like other patent owners, aren’t required to produce products embodying their designs.) Even in the rare case where a design patent claims the entire shape and surface design of a product, that patent will still be infringed by a competitor who makes a product in that shape even if the color or material or some other non-shape attribute is so different that no one would mistake it for the original item.

Many (perhaps most) design patents claim just a small part of a larger design; the whole point of such patents is to capture competing products that don’t look the same overall. When an applicant claims a small part of a design, there is no requirement that it be an important or valuable part—let alone a part that would lead to serious consumer deception. (If you’re interested, I wrote more about these claiming techniques here and here.)

Over the years, I’ve heard many design patent attorneys say they want border enforcement. But it’s not because they’re worried about counterfeiting. They want it because it will make design patents more valuable—or at least seem more valuable—to their clients, which in turn makes it easier to sell their design patent prosecution services. (It’s perhaps not surprising that the push for CBP enforcement became more organized after the Supreme Court’s decision in Samsung v. Apple which, in the eyes of many, made design patents less valuable. The ultimate impact of that case, however, remains to be seen. For more on that case, see here; for more on the developments since then, see here.) While some proponents of this bill may truly, in their hearts of hearts, be worried about actual counterfeiting, the fact remains that many design patent attorneys want border enforcement for these other reasons.

We’ve seen this rhetorical technique before—in the past, proponents of broader copyright laws have used the word “counterfeiting” to conjure the specter of medicines laced with poisons and other horrors to scare legislators into enriching private rights holders. I hope Congress doesn’t fall for it.