In a significant decision with implications for patent litigation practice, the Federal Circuit has vacated both infringement and damages judgments totaling $300 million in Optis Cellular Technology v. Apple Inc., finding multiple errors by the Eastern District of Texas that undermined the validity of the jury's verdict. Judge Prost's opinion identified four distinct areas of reversible error:

- Improper verdict form construction that violated Apple's Seventh Amendment right to jury unanimity,

- Incorrect patent eligibility analysis under 35 U.S.C. § 101,

- Erroneous means-plus-function determination under 35 U.S.C. § 112 ¶ 6, and

- Abuse of discretion in admitting prejudicial settlement evidence under Federal Rule of Evidence 403.

Optis asserted several standard-essential patents (SEPs) covering Long-Term Evolution (LTE; aka 4G) technology against various Apple devices including iPhones, iPads, and Watches. After an initial jury verdict awarding $506.2 million, the district court granted a new trial on damages only, finding that the jury had not heard evidence regarding Optis's FRAND (fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory) licensing obligations. The second jury awarded $300 million as a lump sum for past and future sales.

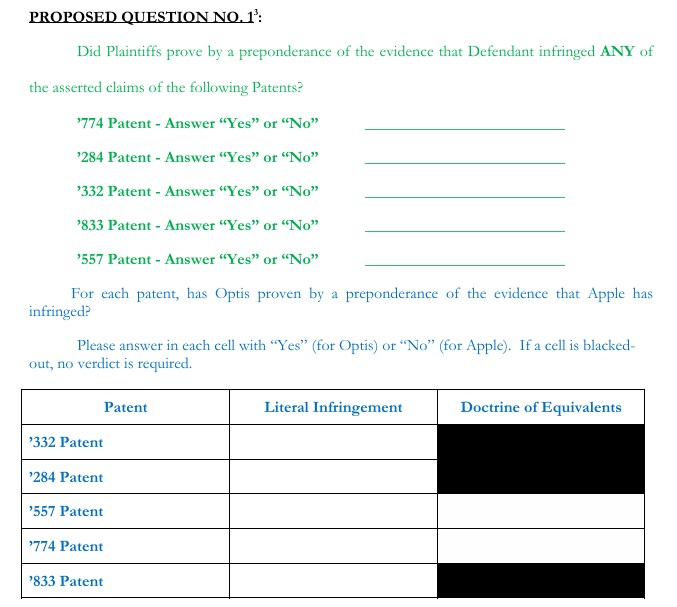

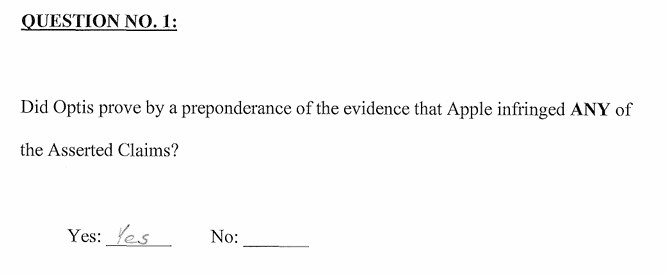

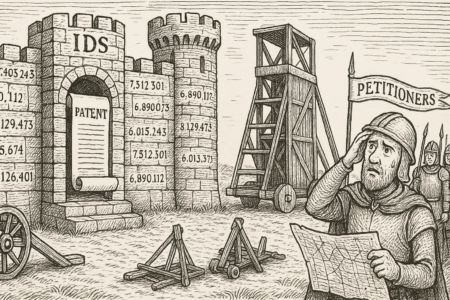

Competing jury form proposals (patentee in green; accused in blue):

Single Broad Verdict Form from Judge Gilstrap

How Much is Hidden in the Jury Black Box: Patent cases are extremely complicated. And, this one involved five separate patents, including allegations of both literal and DOE infringement, willful infringement, and invalidity. In situations like this, district court judges look for ways to simplify the jury decision making. Judges often have legitimate concern that lay jurors will be overwhelmed by highly technical claim constructions and complex infringement theories across multiple patents, potentially leading to decisions based on confusion rather than careful consideration of the evidence. And, judges worry that overly detailed verdict forms increase the risk of logically inconsistent findings, which can complicate post-trial proceedings and create appellate complications.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.