Patent Plaintiffs Continue to Push for Expanded notion of Joint Infringement.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

CAFC: Patent Attorney Has No Right to Defend Himself Against Charges of Inequitable Conduct

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Priority to Foreign Application Requires “Inventor’s Knowledge or Consent” at the Time the Foreign Application was Filed

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

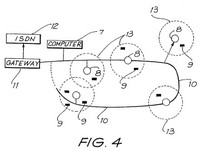

V-Chip Declaratory Judgment Patent Case Reinstated by CAFC

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Summary Judgment of Non-Infringement: Downward Force <> Upward Force

SafeTCare v. Tele-Made (Fed. Cir. 2007).

SafeTCare’s patent covers a bariatric hospital bed designed for obese patients. On summary judgment, the district court found that the Tele-Made beds do not infringe. Other defendants and counterclaims are still pending.

Jurisdiction: On appeal, the CAFC sua sponte questioned jurisdiction. Because the judgment was not complete as to all parties and the judge had not issued a Rule 54(b) order of appealability (See Bashman), the CAFC did not have jurisdiction at the time of oral arguments. However, the CAFC allowed the parties time to ask for such an order from the district court before dismissing the appeal. (This pragmatism is perhaps due to Judge Robinson’s place on the panel).

Non-infringement affirmed.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Reasonable Pertinence may be Sufficient to Combine References in Obviousness Rejection

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Nonpracticing Entity (CSIRO) Gets Injunction

CSIRO operates as a technology licensing arm of the Australian Government. CSIRO does not practice its inventions, but has asserted its wireless LAN patent against a number of accused infringers, including Intel, Microsoft, Marvell, and Buffalo. The patent is broad enough to cover all 802.11a/g wireless technology and has a 1992 priority date.

In the case against Buffalo, CSIRO won a slam-dunk summary judgment of validity and infringement. The court then considered whether to award a permanent injunction in favor of the non-practicing entity (NPE).

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Procedure: Expert Testimony Deserves Weight on Summary Judgment

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

No Appellate Jurisdiction For Appeal of Preliminary Injunction Contempt Order

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Monsanto v. McFarling: CAFC Affirms “Reasonable Royalty” of 140% of Purchase Price

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

CAFC Affirms Disqualification of Defendant’s Attorneys

In re Hyundai Motor Am., 185 Fed. Appx. 940 (Fed. Cir. 2006)

Orion IP has accused dozens of companies of infringement of its business method patents ("computer-assisted sales"). At one point, Orion worked with the Orrick firm on some matters and Orrick made a pitch to handle Orion's litigation and patent strategy work. Orion demurred. Once litigation began, Orrick got back in the game by agreeing to represent several of the accused infringers directly adverse to Orion.

The Texas district court noted a conflict-of-interest and disqualified Orrick. On writ of mandamus, the CAFC affirmed -- finding no error.

The parties apparently presented diverging evidence as to the subject-matter of early meetings between Orrick and Orion and the type of documents exchanged. The CAFC noted that these were purely factual questions that the lower court "resolved in Orion's favor" without any clear error.

In order to prevail, Hyundai must clearly and indisputably show clear error in the district court's findings of fact and application of the facts to the law. Hyundai has not carried its burden. This is essentially a factual dispute, which the district court resolved in Orion's favor. The district court held a hearing, considered the competing declarations, and reviewed the pertinent documents. We do not find a basis for overturning those findings.

Disqualification affirmed.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Claim Transitions: "Comprising The Steps Of"

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Microsoft v. AT&T: Transnational patent Law

Microsoft v. AT&T (Supreme Court 2007).

Section 271(f) of the Patent Act expands the territorial scope of US patent protection by creating liability for exporting one or more “components” of a patented invention so that the whole invention may be practiced abroad. The statute is divided into parts one and two dealing with inducement and contributory activity respectively.

The case at hand involves Microsoft’s infringement of AT&T’s speech coding technology patent. Microsoft has conceded that its software (once installed on a computer) infringes the patent in the US. However, Microsoft has fought against paying patent royalties for sale of the same software abroad. Microsoft’s argument, spelled out in its brief, is two-fold: (1) Software cannot be a ‘component’ as required by the statute because software code is intangible; and (2) Software copies made abroad cannot be considered ‘supplied’ from the US as required by the statute because no physical particle that Microsoft exported actually became part of the finished product. I have previously labeled these arguments as the tangibility requirement and the molecular conservation requirement. [Link]

Now, AT&T and its supporters has filed their briefs that explain why 271(f) should encompass foreign copies of software shipped from the US. [Petitioner and Gov’t briefs are discussed here]

AT&T’s Brief on the Merits:

Tangibility: AT&T attacks the tangibility requirement head-on, arguing that there is no such requirement.

[The software] is plainly a component of [the patented] device, just as a unique collection of intangible words is a component of any book bearing the title Moby-Dick, even though those words, too, must be combined with ink and paper before the book can be read.

Of course AT&T is correct — the statute does not spell-out any tangibility requirement, and Microsoft’s statutory argument is, at best implicit. AT&T’s arguments are supported by business practice as well. Software and hardware are developed and sold separately, and each side can easily be though of as providing components of the whole.

Molecular Conservation Requirement: AT&T takes a different view of the statutory requirement that the components be “supplied” from the US. In AT&T’s story, “supplied” means satisfying a need or furnishing. Using a but-for analysis, AT&T makes clear that without Microsoft’s shipment of the code abroad, it would not have ended-up in the foreign computers.

Here, the Windows object code is present in the foreign made computers only because Microsoft “provided” or “furnished”—in a word, supplied—it from the United States, via golden master disk or electronic transmission.

As it stands, the AT&T brief is well written and convincing on its own — the major problem being that it leads with a petty argument for dismissal.

Philips Corporation also filed a brief in support of AT&T. Philips makes several arguments, two of which I discuss here:

- In today’s market, software and hardware companies do compete head-to-head. A finding that software export is noninfringing would be at the expense of electronics companies because hardware exports would continue to be considered infringing. Thus, awarding the win to Microsoft here may free the software industry, but will even further damage the hardware export industry.

- In many ways, this case is about the size of damages. Microsoft hopes that copies made abroad will not be seen as infringing because those copies were not literally shipped from the US. Philips points out under the rules of consequential damage calculations, Microsoft would owe damages for sales of all copies even if 271(f) only covered the initial master disk shipment.

WARF, California, and RCTech filed a joint brief in support of AT&T. These holders of strong bio-related patents see the potential that this case could narrow the scope of their protection. WARF points-out how Microsoft comes to the table with unclean hands:

When it suits its interests, even Microsoft acknowledges that the number of units it supplies is not limited by the number of golden masters it sends abroad. In Microsoft Corp. v. Comm’r of Internal Revenue, Microsoft argued that it was entitled to tax deductions . . . for all foreign sales of software replicated from Microsoft’s golden master abroad, claiming that such copies were "export property" under the statute. The Ninth Circuit . . . agreed with Microsoft that all copies created from the golden master were export property, thereby providing Microsoft with another $31 million in claimed deductions for 1990 and 1991.

BAYHDOLE25.inc is an educational NGO that supports, as you might guess, the Bayh Dole act (at its 25th anniversary). In a brief supporting AT&T, BD25 argues for the protection of intangible assets — especially assets that are replicable and intended to be replicated. These include software code, cell lines, patented seeds, DNA, etc. Replicable assets are important and should be protectable.

Documents:

- On the Merits

- In Support of Microsoft

- Petitioner: Microsoft Brief;

- Amicus: US Government;

- Amicus: Law Professors (Lemley & Duffy);

- Amicus: Amazon;

- Amicus: SIIA (Industry Org.);

- Amicus: SFLC (Moglen & Ravicher);

- Amicus: Shell Oil (Method Claims);

- Amicus: Intel;

- Amicus: AIPLA;

- Amicus: Eli Lilly;

- Amicus FICPI;

- Amicus Autodesk

- Amicus BSA (Industry will be destroyed if AT&T wins);

- Amicus Yahoo!.

- Respondent: AT&T;

- Amicus: BayhDole25.inc;

- Amicus: US Philips;

- Amicus: UC WARF RCTech.

- Amicus: Professor Edward Lee.

- Petitioner: Microsoft Reply Brief.

- Petitioner: Microsoft Petition

- Petitioner: Microsoft Petition Appendix

- Respondent: AT&T Opposition

- Petitioner: Microsoft Reply in Support

- Respondent: AT&T Supplemental Brief

- Petitioner: Microsoft Supplemental Brief

- Amicus: Software and Information Industry Association in Support of Microsoft

- Amicus: Government in Support of Microsoft

Important recent 271(f) cases:

- NTP v. Research in Motion, (271(f) “component” would rarely if ever apply to method claims).

-

AT&T v. Microsoft, 414 F.3d 1366 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (271(f) “component” applies to method claims and software being sold abroad);

-

Union Carbide v. Shell Oil (Fed. Cir. 2005) (271(f) “component” applies to method claims).

-

Eolas v. Microsoft, 399 F.3d 1325 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (271(f) “component” applies to method claims and software);

-

Pellegrini v. Analog Devices, 375 F.3d 1113 (Fed. Cir. 2004) (271(f) “component” does not cover export of plans/instructions of patented item to be manufactured abroad);

-

Bayer v. Housey Pharms, 340 F.3d 1367 (Fed. Cir. 2003) (271(g) “component” does not apply to importation of ‘intangible information’).

Earlier Discussion of this case

- https://patentlyo.com/patent/2006/12/microsoft_v_att.html

- I will be discussing this and other extraterritorial issues at Duke University Law School on February 23, 2007. Link.

Text of 35 USC 271(f)

(1) Whoever without authority supplies or causes to be supplied in or from the United States all or a substantial portion of the components of a patented invention, where such components are uncombined in whole or in part, in such manner as to actively induce the combination of such components outside of the United States in a manner that would infringe the patent if such combination occurred within the United States, shall be liable as an infringer.

(2) Whoever without authority supplies or causes to be supplied in or from the United States any component of a patented invention that is especially made or especially adapted for use in the invention and not a staple article or commodity of commerce suitable for substantial noninfringing use, where such component is uncombined in whole or in part, knowing that such component is so made or adapted and intending that such component will be combined outside of the United States in a manner that would infringe the patent if such combination occurred within the United States, shall be liable as an infringer.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Threats Against Customers Lead to Walker Process Antitrust Claim

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

CAFC: “Circuit means” interpreted as means-plus-function

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

CAFC: Construction of Essential Features and Impermissible Recapture

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

CAFC: Meaning of “About”

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Collateral Estoppel Does Not Extend to Preliminary Injunction Findings

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

ITC: Standing to Appeal

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.