After being rejected by the district court, the USPTO has appealed its case to the Federal Circuit. On appeal, the USPTO asks the appellate court to allow the patent agency to implement new rules that place limits on the number of claims filed with each patent application and the number of continuations that may stem from each patent application. [File Attachment: pto tafas brief (144 KB)]

The PTO asks the CAFC to review three specific issues:

- Whether the PTO's new limits on claims and continuations are within the scope of the Office's statutory rulemaking authority;

- Whether the new limits conflict with the Patent Act; and

- Whether the PTO must provide additional notice and comment for its rule changes.

The PTO summarizes its arguments as follows:

1. The Final Rules are within the scope of the USPTO's rulemaking authority under the Patent Act. The Act's primary grant of rulemaking authority, Section 2(b)(2), authorizes the Office to issue rules that "govern the conduct of proceedings in the Office," "facilitate and expedite the processing of patent applications," and "govern the recognition and conduct of agents, attorneys, or other persons representing applicants or other parties before the Office." The USPTO correctly determined that the Final Rules fit within these grants of rulemaking authority. By setting filing and documentation requirements, the rules regulate the conduct of proceedings in the Office and the conduct of attorneys and other representatives, and by discouraging unnecessarily repetitive filings and providing examiners with needed information, they facilitate and expedite the processing of patent applications.

In holding that the Final Rules are ultra vires, the court made no effort to measure the Final Rules against the actual terms of Section 2(b)(2), nor did the court give the USPTO's interpretation of that provision the deference required by Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837 (1984), and its progeny. Instead, the court held that the Office is confined to issuing procedural rules and that the Final Rules are impermissibly substantive. But the cases on which the district court relied do not engraft a rigid procedural/substantive distinction onto Section 2(b)(2). And even if they did, the Final Rules would still pass muster, for they regulate the procedures used in proceedings before the Office rather than the substantive criteria for the awarding of patents. The district court's conclusion that the rules are substantive rather than procedural rests on APA cases that do not involve that distinction at all, and the court's standards for measuring the "substantiveness" of rules are at odds with the Supreme Court's jurisprudence under the Rules Enabling Act.

The court compounded these errors by erroneously holding that Section 2(b)(2)(B), which provides for the USPTO to issue rules "in accordance with" 5 U.S.C. § 553, requires the Office to engage in notice-and-comment rulemaking even when Section 553 expressly provides that notice and comment are not required.

2. In the course of its ultra vires analysis, the district court held that the Final Rules are inconsistent with other provisions of the Patent Act. That holding is likewise incorrect. The court mischaracterized the effects of the Final Rules, misconstrued the statutory provisions, misunderstood the judicial precedents concerning those provisions, and failed to give the USPTO's construction of the provisions the deference required by Chevron.

The district court held that Rules 78 and 114 conflict with Section 120 and 132(b), respectively, because the rules place "hard limits" on the number of continuation applications and RCEs that an applicant may file, while the statutory provisions entitle applicants to make an unlimited number of such filings. But the rules do not in fact limit the number of continuation applications and RCEs that may be filed; they simply require an applicant to show the need for further filings once a threshold number of filings has been made. And even if the rules did impose fixed limits, they would not conflict with Sections 120 and 132(b). Section 120 was enacted by Congress simply to provide a statutory basis for continuation practice, not to vest applicants with the right to file an endless stream of continuation applications.

Likewise, Section 132(b), which directs the Office to issue regulations providing for continued examinations, does not entitle applicants to file an endless series of RCEs. The district court held that Rules 75 conflicts with Section 112 ¶2 by limiting the number of claims that may be included in a single application. But Rule 75 places no limit whatsoever on the number of claims in an application, and Section 112 ¶ 2 does not address the permissibility of such a limit in any event. The court also held that Rule 75 and 265 conflict with the provisions of the Patent Act that assign the USPTO the burden of examination and the burden of establishing a prima facie case of unpatentability. But there is no conflict between those provisions and the rules, which merely require applicants to provide information about their claims and prior art so examiners can discharge their burdens more accurately and efficiently.

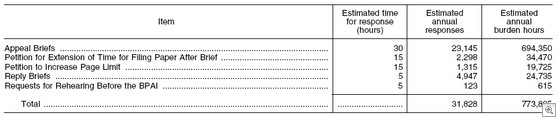

New PTO Fees: Up 5% to account for inflation. [

New PTO Fees: Up 5% to account for inflation. [