by Dennis Crouch

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit recently affirmed a finding by Western District of Texas Judge Alan Albright that certain claims in two patents owned by WSOU Investments LLC were invalid as indefinite under 35 U.S.C. §112. WSOU Invs., LLC v. Google LLC, Nos. 22-1066, -1067 (Fed. Cir. Sept. 25, 2023). Although the decision is designated nonprecedential, it includes a number of interesting lessons on the requirements for definiteness and disclosure of corresponding structure under 35 U.S.C. §112.

The Technology at Issue

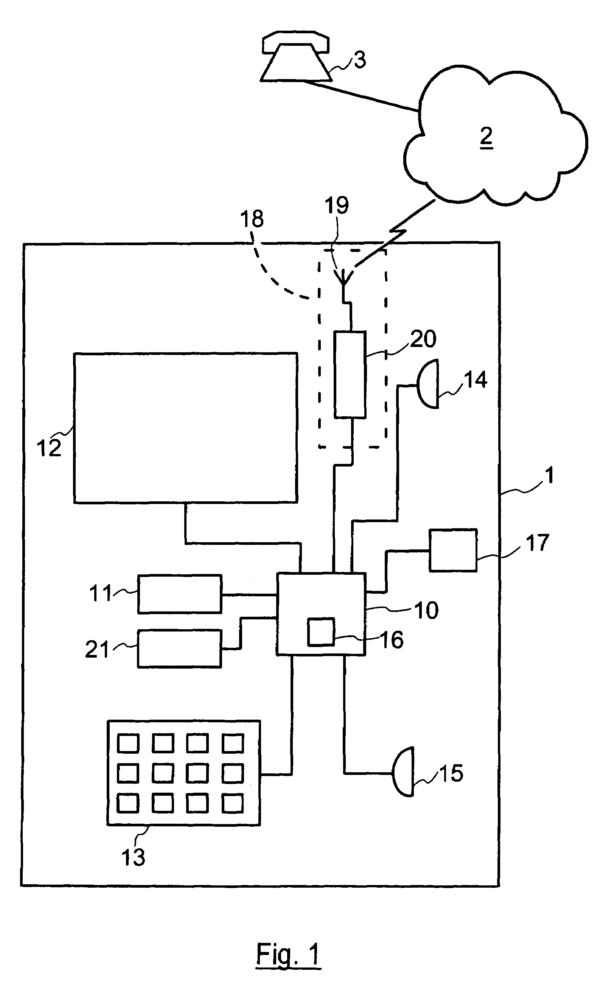

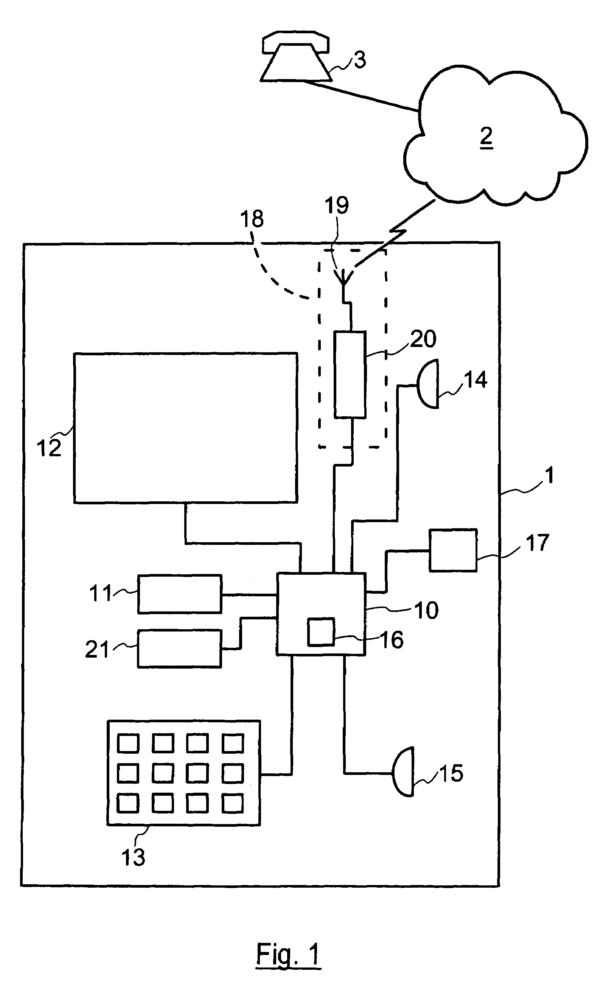

The first patent at issue was U.S. Patent No. 7,304,563 (“the ‘563 patent”), entitled “Alarm clock.” This patent claimed an alarm clock feature for mobile phones where the alarm involved initiating a connection to another device over a network to cause that device to signal the alarm.

Claim 16 is is recited in means-plus-function form:

issuing means for issuing an alert when the current time matches the alert time by initiating a connection to another communication terminal over a network so as to cause that other terminal to locally signal the incidence of the connection incoming thereto

‘563 Patent, claim 16. Claim 16 is clearly written in means-plus-function form, but the focus of the appeal was on claim 1, which was substantially similar. The key difference though is that the claim 1 limitation was directed to “an alerting unit” rather than an “issuing means:”

an alerting unit configured to issue an alert when the current time matches the alert time, the alerting unit being configured to issue the alert by initiating a connection to another communication terminal over a network so as to cause that other terminal to locally signal the incidence of the connection incoming thereto

‘563 Patent, claim 1. Judge Albright found both claims to be in means-plus-function form and the Federal Circuit affirmed on appeal.

In patent law, “means-plus-function” (MPF) claiming is a way to define an element of a patent claim by the function it performs rather than by its specific structure. This type of claiming is governed by 35 U.S.C. § 112(f), which allows patentees to express a claim limitation as “a means or step for performing a specified function.” When a claim is interpreted under § 112(f), the claim limited to the specific structure disclosed in the specification and equivalents thereof. This limitation to actually disclosed structure (and equivalents) severely limits the scope of MPF claims that often seem much broader when read in the abstract. But, the beauty of MPF analysis is that it is designed to preserve the validity of claims that might be unduly indefinite, not enabled, or even extent to ineligible subject matter. Patentees often fall into the common trap of using of MPF limitations without providing adequate structure within the specification. If no structure is disclosed in the specification for a means-plus-function (MPF) claim, the claim is deemed indefinite and therefore invalid. In re Donaldson Co., 16 F.3d 1189 (Fed. Cir. 1994).

The Federal Circuit has established a two-step framework for determining whether a claim limitation is subject to MPF construction under 35 U.S.C. 112(f). First, the court must determine if the limitation uses the term “means.” If so, a rebuttable presumption is triggered that 112(f) applies. Williamson v. Citrix Online, LLC, 792 F.3d 1339 (Fed. Cir. 2015). Prior to Williamson, there was a strong presumption associated with use of the word “means.” In particular, courts generally assumed that a claim term that did not use the word “means” was not subject to § 112(f) interpretation. Williamson altered this landscape by holding that the presumption can be quickly overcome, even if the word “means” is not present, if the claim term fails to recite sufficiently definite structure or else recites a function without reciting sufficient structure for performing that function.

In Williamson, the court noted that patentees had begun using various “nonce words” that were effectively non-limiting placeholders designed to avoid MPF interpretation. Here, for instance, the claimed “alerting unit” is roughly equivalent to a means-for-issuing-an-alert. The presumption against MPF can quickly be overcome in situations where the patentee uses a nonce word to designate the element if the limitation generally fails to recite sufficiently definite structure.

Looking particularly at claim the court first noted the rebuttable presumption against means-plus-function treatment since Claim 1 is directed to a “unit” and does not use the term “means.” In rebutting the presumption, the court agreed with Judge Albright that in the context of the claims and specification, the term “unit” was defined only by the function it performs, rather than connoting any specific structure. In its analysis, the court held that the language surrounding “alerting unit” in the claim consisted of purely functional language that provided no structural context. Terms like “configured to issue an alert” and “initiating a connection” were purely functional. The court also looked to the specification to see how the “alerting unit” phrase was used — finding that it was also described in the same purely functional terms as the claim language. In the end, the appellate panel agreed with the district court that “unit” and “means” were used interchangeably in the patent, indicating “unit” was a generic placeholder rather than structural term.

The patentee WSOU had offered expert testimony on point, but the appellate court rejected the extrinsic evidence for its attempt to be a “gap filler.”

To the extent that WSOU argues that the ‘interpretation of what is disclosed in the specification must be made in the light of knowledge of one skilled in the art,’ it invites us to improperly use the knowledge of a skilled artisan as a gap-filler, rather than a lens for interpretation. WSOU argues that a skilled artisan would ‘understand the structure involved with a mobile phone using GSM ….

However, those arguments are irrelevant as The indefiniteness inquiry is concerned with whether the bounds of the invention are sufficiently demarcated, not with whether one of ordinary skill in the art may find a way to practice the invention.

WSOU (internal citations and quotations removed). This quote from the appellate panel rejects WSOU’s attempt to use expert testimony regarding PHOSITA to overcome the lack of structural disclosure in the specification. The court emphasizes that gaps in the specification cannot be filled by skilled artisan knowledge during the 112(f) analysis.

Having determined that claim 1’s “unit” was in MPF form, the court then moved to the next step — looking for the corresponding structure within the specification to perform the claimed function. On appeal, the appellate panel again agreed with Judge Albright that no such structure had been disclosed. The court examined the disclosed processor, communication engine, antenna, and communication protocols , but found no clear link between these components and the claimed function of “initiating a connection to another communication terminal over a network.” Rather, the specification disclosed these structures in a general sense without specifically tying them to the network connection function. Merely mentioning general components is insufficient to provide corresponding structure for a means-plus-function limitation. Because the patentee failed to disclose adequate structure for the “alerting unit” limitation under 112(f), Claim 1 was held invalid as indefinite.

For the ‘563 patent, the court determined that the “issuing means” limitation in Claim 16 was subject to 35 U.S.C. §112(f), which governs interpretation of means-plus-function claim limitations. The court identified two functions for this means-plus-function limitation: (1) initiating a network connection to another device, and (2) causing signaling means to locally signal the user. The court held that the specification failed to disclose sufficient structure corresponding to either of these functions, and therefore the claim was indefinite under §112(f). The court reached the same conclusion regarding the similar “alerting unit” limitation in Claim 1.

I quibble with the Federal Circuit’s doctrine on MPF indefiniteness. In particular, the court’s precedent creates an if-then approach: if no sufficient structure then automatically indefinite. I would suggest an additional step asking whether the claim provides reasonably certain scope, recognizing that 112(f) was particularly designed to permit flexibility using narrowing of claims rather than invalidation.

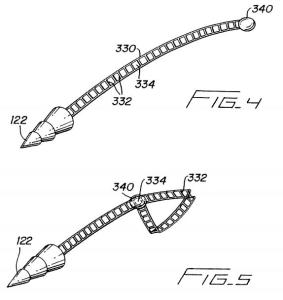

The second portion of the appeal focused on U.S. Patent No. 8,238,681 that appears to include a pretty big typo within its claims:

the plurality of parts [including] a first part closest to a center, a third part farthest from the center, and a second part in between the first part and the second part.

‘681 patent, claim 1 (simplified). You can see that the claim requires a “second part” located between the first and second part. Nonsense. It is pretty clear to me that the patentee intended (but did not claim) that the second part would be between the first and third parts. Unfortunately for the patentee, this exact typo was also found within the specification, and the patent did not include a clear drawing showing the correct aspect.

The court emphasized that it cannot redraft claims to contradict their plain language, even to make them workable.

We have explained repeatedly and consistently, ‘courts may not redraft claims, whether to make them operable or to sustain their validity.’ Chef Am., Inc. v. Lamb-Weston, Inc., 358 F.3d 1371 (Fed. Cir. 2004). Even ‘a nonsensical result does not require the court to redraft the claims of the [patent at issue]. Rather, where as here, [when] claims are susceptible to only one reasonable interpretation and that interpretation results in a nonsensical construction of the claim as a whole, the claim must be invalidated.’ Id.

Slip OP.

The patents here were both originally owned by Nokia. They were later transferred to WSOU, a patent assertion entity associated with Craig Etchegoyen, a former CEO of another patent assertion entity, Uniloc.