Plaintiff has Burden of Establishing Proper Venue in Patent Cases

by Dennis Crouch

In re ZTE (Fed. Cir. May 14, 2018) is an important case establishing that the plaintiff has the burden of proving proper venue in patent cases.

In May 2018, the Federal Circuit denied HTC’s writ-of-mandamus request on improper-venue grounds — holding that – like most issues – appeal of improper venue decision should ordinarily wait until final judgment. See, Dennis Crouch, The US Venue Laws Do Not Protect Alien Defendants, Patently-O (May 9, 2018); In re HTC Corp., 2018 U.S. App. LEXIS 12182 (Fed. Cir. 2018). Less than one-week-later, the Federal Circuit has swung the other way — this time granting ZTE’s motion for writ of mandamus on the issue of improper venue. The ZTE panel (Judges Reyna, Linn, Hughes) did not cite HTC, nor are there any overlapping judges with the HTC panel (Chief Judge Prost, and Judges Wallach and Taranto). Of course, TC Heartland was an improper venue case that went to the Supreme Court on mandamus.

Here, the panel explained that mandamus makes sense because the decision resolves two “basic and undecided” issues of venue law: (1) What law to apply on the question of burden-of-proof for proper venue; and (2) Which party has the burden of showing proper/improper venue.

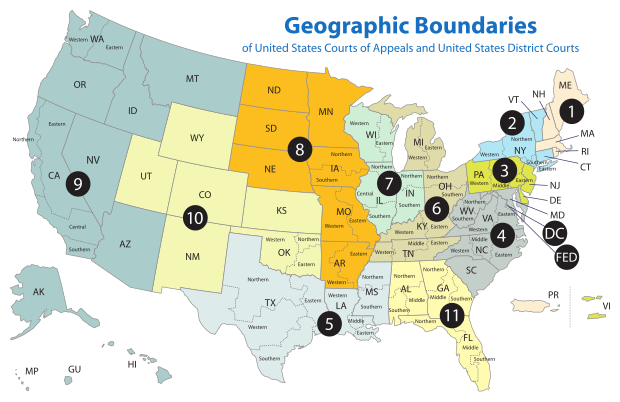

Federal Circuit Law: Each region within the US has its own court-of-appeals that guides lower courts in their decision making. Patent lawsuits are filed in these same regional courts, but the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit hears those appeals. The courts are all applying the same law, but differences in practice and interpretation have developed (i.e., Circuit Splits). In the patent world, the Federal Circuit has developed a practice of having the lower courts use their regional circuit law and procedure as a baseline, but then apply Federal Circuit law to issues unique to patent law. See Biodex Corp. v. Loredan Biomed., Inc., 946 F.2d 850 (Fed. Cir. 1991).

In TC Heartland, the Supreme Court ruled that patent-venue is a unique patent law question. Here, the Federal Circuit has extended that general principle to hold that sub-determinations such as burdens-of-proof related to improper venue challenges are also issues of patent law for the Federal Circuit to decide.

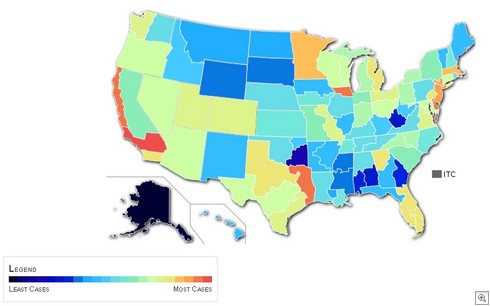

Burden of Persuasion in Venue Law: The question of who has the burden of persuasion in venue law is interesting. On the one hand, it appears to be the plaintiff’s burden to file the case in a proper venue. On the other hand, it is the defendant who files the FRCP 12(b)(3) motion to dismiss for improper venue. The regional circuit courts do not offer much help because they are divided on the issue with reference to the general venue statute.

In this case the appellate panel found that 1400(b) is a restrictive measure – particularly limiting venue in patent cases — and that intentional narrowness suggests that the plaintiff should have the burden of showing proper venue. This fits in line with Moore’s Federal Practice explanation.

It makes good sense to require a defendant who seeks dismissal of an action because of this personal privilege to establish the privilege. Placing the burden on the plaintiff is justified only in a case involving an exclusive venue statute, such as in patent infringement cases, in which venue lies in the district where the infringement takes place. Because the plaintiff has the burden of proving patent infringement, it makes sense to shift the burden of proof on the venue issue to the plaintiff, and the courts have so held.

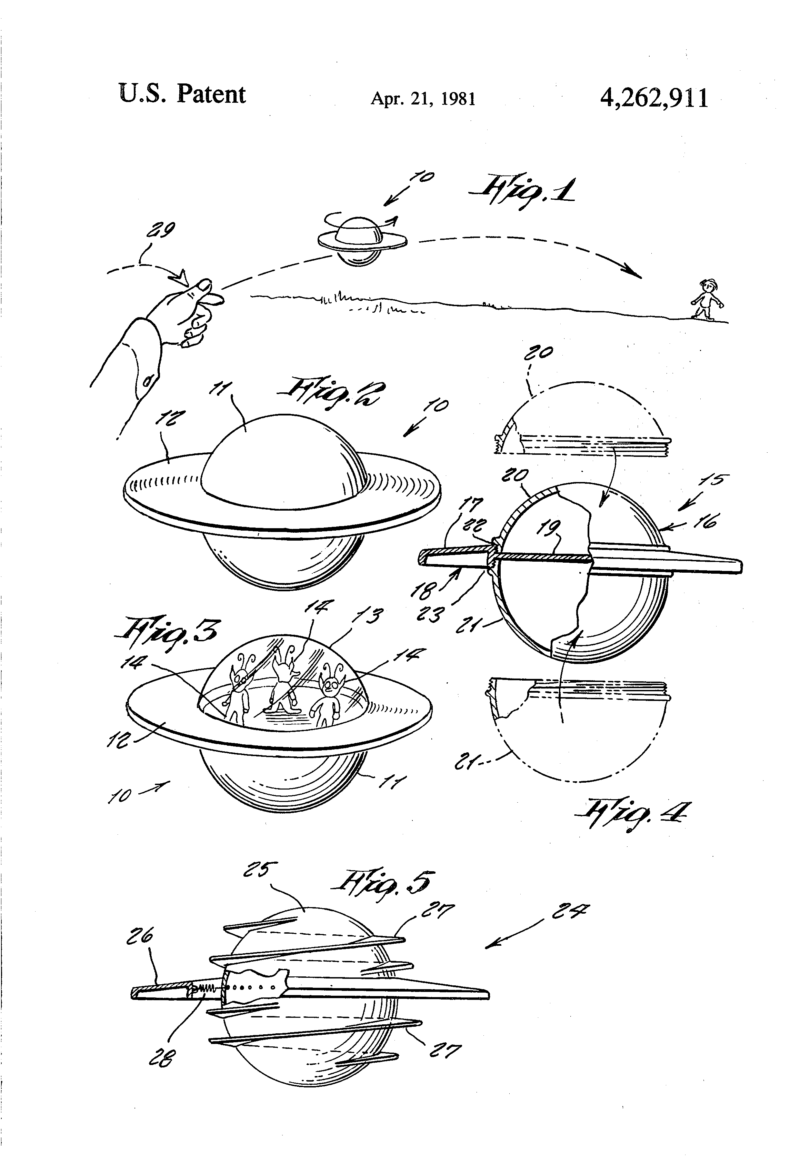

17-110 Moore’s Federal Practice – Civil § 110.01[5][c] (2018). (Note that when Moore’s state that “courts have so held”, the accompanying footnote only cites one 1981 district court case. Hoffacker v. Bike House, 540 F. Supp. 148, 149–150 (N.D. Ca. 1981)).

Here, the district court had placed the burden on the defendant ZTE of proving improper venue – on remand that burden needs to shift. The appellate panel went on to caution the lower court about finding a “regular and established place of business” in E.D. Texas based upon an “arms-length contract for service” with a call center provider.

Notes:

- Although the plaintiff has the burden of proving proper venue, it does not appear that the court here changed the usual notion that proper venue need not be alleged in the complaint itself. Rather, the defendant must challenge proper venue. Ordinarily for such a challenge to be recognized must surpass some burden of presentation — i.e., by making a plausible or prima facie case of improper venue.