Decision on American Axle Within the Week

Animated Design Patents

Guest Post by Sarah Burstein, Professor of Law at the University of Oklahoma College of Law

Wepay Global Payments LLC v. PNC Bank, N.A. (W.D.Pa. June 1, 2022) [wepayDecision]

Companies associated with William Grecia have filed over a dozen cases alleging infringement of design patents for “animated graphical user interfaces.” A judge in one of those cases, Wepay v. PNC Bank, recently issued a decision dismissing the case.

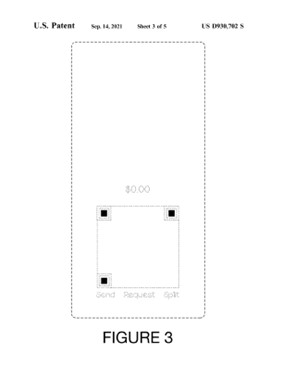

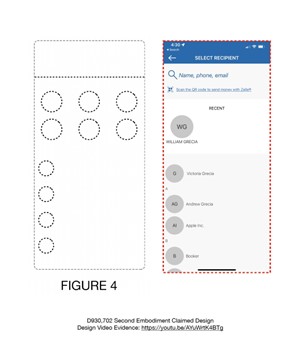

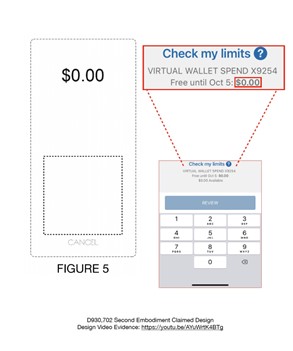

The patent asserted in that case, U.S. Patent No. D930,702, was issued in 2021 and claims a “design for a display screen portion with animated graphical user interface.” Wepay alleges infringement of the second embodiment, which includes three images:

|

|

|

Consistent with the USPTO’s rules for “changeable computer generated icons,” see MPEP § 1504.01(a)(IV), the patent specifies that, “[i]n the second embodiment, the appearance of the sequentially transitions between the images shown in FIGS . 3 through 5. The process or period in which one image transitions to another image forms no part of the claimed design.” Consistent with the USPTO’s general drawing rules, the patent disclaims all matter shown in broken lines “form[] no part of the claimed design.”

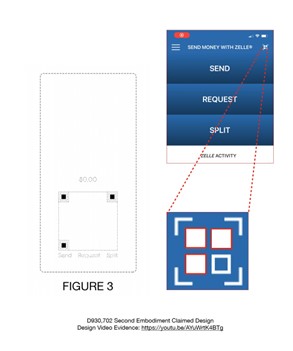

So what does this patent cover? According to the court, Wepay seemed to think its patent covered any app with a QR code that lets you send money to other people:

WPG maintains that both its patent and the PNC app include an icon array of three squares that simulate a QR code; both cycle to a functional screen where the user may choose to whom the money will be sent; and both conclude with the display screen with a display of a zero value, where the user may input the amount of money that the user wishes to send.

The court rejected that interpretation—and rightly so. It’s well-established that design patents cover the visual designs that are actually claimed, not the larger design concepts.

The court held that the claimed designs and accused design, shown below as shown in the complaint, were plainly dissimilar and granted PNC’s motion to dismiss.

|

|

|

In doing so, the court recognized that placement and proportion matter in design, noting that “[a]ny similarity between the two designs is limited to basic geometric shapes, but with notable differences in shape size and spacing such that no ordinary observer would mistake the Accused Design with the Asserted Design or vice versa.”

Some may argue that the court erred in considering the placement and proportion of the claimed design fragments, because matter shown in dotted lines “forms no part of the claimed design.” But even if other visual portions of the design are disclaimed, that doesn’t mean courts have to treat the claimed portions as free-floating motifs. (Indeed, sophisticated design patent owner Nike has recognized that placement matters, even when dotted lines are used. See this PTAB decision at 10-13.)

I’ve explained here, placement and proportion are essential elements of design. The differences between the claimed and accused designs here are an excellent example of how different a single motif (e.g., each of the three squares in figure 3 and in the accused design) can look in the context of the design, depending on its proportion to the other elements and where it is located on the screen.

Before diving into the merits, however, the court expressed some doubt over whether infringement was even possible in this case:

[T]he Court notes that the ordinary observer test focuses on a hypothetical purchaser induced to buy a product with an accused design over an asserted design. The cases cited by the parties likewise address designs where there exists a consumer and/or purchaser at play. However, neither the cited cases nor this Court’s research reveals a case where, like the instant matter, the consumer has not voluntarily chosen the design at issue. Instead, the Accused Design is incidental to the PNC customers utilization of the mobile application. The Complaint does not allege that a purchaser would have been or has been involved with the Accused Design. Further, the Complaint does not allege a purchase or transaction by a consumer with regard to the Accused Design over the Asserted Design. Thus, the ordinary observer test would seem not to fit squarely with the designs at issue, and WPG would not be able to assert a design patent infringement claim.

Even though it’s dicta, the court’s suggestion that a design patent owner must plead “a purchase or transaction by a consumer with regard to the Accused Design over the Asserted Design” is worth further discussion.

Like other patents, a design patent is infringed when someone makes, uses, sells, offers to sell, or imports the patented invention without permission. The test for design patent infringement doesn’t change that. It just tells us when someone is making, using, selling, offering to sell, or importing the patented design.

The test for design patent infringement is a test of visual similarity. The “ordinary observer” part just tells us how similar the designs must be. (See this article at page 177.)

So, under current law, no sale is required, let alone—as the court seems to suggest—a direct sale to the end user, “with regard to the Accused Design over the Asserted Design.” Indeed, because there is no working requirement for design patents, there may not be a product embodying the claimed design available for sale.

All the defendant has to do is make (or sell, etc.) a product that looks “the same” as the claimed design. (For more on how the test for design patent infringement works, see this essay or Chapter 12 of this free casebook.)

Because Grecia-related companies have filed so many similar cases, it seems likely this decision will be appealed. It is definitely one to watch.