April 2020

Tweets on Georgia v. Public Resource

https://twitter.com/jkosseff/status/1255125475686592515

https://twitter.com/CJSprigman/status/1254786676125130754

https://twitter.com/carlmalamud/status/1254899150971301889

USPTO Rejects AI-Invention for Lack of a Human Inventor

by Dennis Crouch

Sometimes I think of myself as the creativity machine. A cool part of this system is that I have a right to seek and obtain patent protection for my inventions (if any). The USPTO is treating Mr. Dabus differently. When Dabus filed for patent protection in 2019, the examiner refused to examine the patent and the PTO Commissioners Office has confirmed the refusal.

The problem is that Mr. Dabus (DABUS) is not human, but rather is a machine – a creativity machine. (more…)

Supreme Court Expands Penumbra of Gov’t Edicts Doctrine: Official Annotations to Code Not Copyrightable

Georgia v. Public.Resource.Org, Inc. (Supreme Court 2020)

The State of Georgia claims copyright to its Annotated Official Code (Official Code of Georgia Annotated (OCGA)). The (e)book includes every Georgia statute and a set of annotations (including summaries of cases and articles discussing the statutes). The OCGA is created by a state entity – the Code Revision Commission – directed by the state legislature. LexisNexis actually did the work of writing the annotations, but copyright (if any) originated with Georgia as a work-made-for-hire.

Public.Resource.Org (PRO) is a nonprofit organization facilitates public access to government records. PRO copied the OCGA and began freely distributing it to the public. Georgia then sued for copyright infringement.

After some amount of litigation, Georgia eventually stopped arguing that the statutes themselves were protectable by copyright. However, the state continued to argue that the annotations were copyrightable since they did not carry the force of law.

The Supreme Court has now sided with PRO and against the state – holding that the government edicts doctrine prohibit copyright on the annotations.

Over a century ago, we recognized a limitation on copyright protection for certain government work product, rooted in the Copyright Act’s “authorship” requirement. Under what has been dubbed the government edicts doctrine, officials empowered to speak with the force of law cannot be the authors of—and therefore cannot copyright—the works they create in the course of their official duties. . . .

[This doctrine] applies to non-binding, explanatory legal materials created by a legislative body vested with the authority to make law. Because Georgia’s annotations are authored by an arm of the legislature in the course of its legislative duties, the government edicts doctrine puts them outside the reach of copyright protection.

Slip Op. Chief Justice Roberts penned the majority opinion that was joined by Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, Gorsuch, and Kavanaugh. Two dissenting opinions: Justice Thomas (with Justice Alito, and Justice Breyer except FN6); and Justice Ginsburg (with Justice Breyer). The split here does not fall along typical liberal-conservative grounds, but does suggest a generational shift — with the five youngest in the majority, and the four eldest siding with the State. (All of the justices are well over the median age of US citizens).

The majority opens with a controversial statement linking copyright with monopoly: “The Copyright Act grants potent, decades-long monopoly protection for ‘original works of authorship.'” Often, as here, courts refer to patents & copyrights as “monopolies” when they are ready to invalidate or weaken the rights granted. See also, Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc., 464 U. S. 417 (1984).

The majority opinion also disparages fair use as insufficient:

If Georgia were correct, then unless a State took the affirmative step of transferring its copyrights to the public domain, all of its judges’ and legislators’ non-binding legal works would be copyrighted. And citizens, attorneys, nonprofits, and private research companies would have to cease all copying, distribution, and display of those works or risk severe and potentially criminal penalties. §§501–506. Some affected parties might be willing to roll the dice with a potential fair use defense. But that defense, designed to accommodate First Amendment concerns, is notoriously fact sensitive and often cannot be resolved without a trial. Cf. Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enterprises, 471 U. S. 539, 552, 560–561 (1985). The less bold among us would have to think twice before using official legal works that illuminate the law we are all presumed to know and understand.

Id. According to its new reinvigoration, the government edicts doctrine does have some clear limits — it only applies to works created by those with “authority to make or interpret the law.”

In this case, the folks at Westlaw make their own annotated version that is likely protected by copyright (assuming originality). As part of his dissent, Justice Thomas notes that Official Code (by LexisNexis) sells for $404 while WestLaw’s version is $2,570. LexisNexis agreed to sell at its “low” price as part of the deal with the state, and the state argued that copyright is instrumental in facilitating creation of high-quality annotations. Otherwise, it just won’t happen. Siri, follow up in two years to see whether this prediction turns out to be true.

Upcoming big issues on this front include the various building codes that are typically created by non governmental entities, but then adopted by various municipal governments.

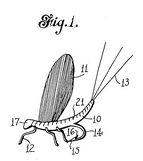

Many an angler has gone fishing and returned empty handed

by Dennis Crouch

In re Rudy (Fed. Cir. 2020)

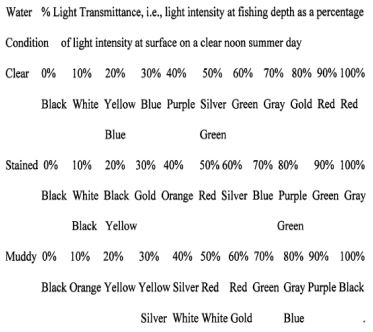

The claim at issue has three basic steps:

- Observe the water and determine whether it is clear, stained, or muddy;

- Measure light transmittance in the water at the depth where the hook will be placed; and

- Use above observation and measurement and the lookup table below to choose a fishing hook color:

In the appeal, the Federal Circuit agreed with the PTO that the hook color selection is a “mental process” that relies upon generalized actions of “collecting” and “analyzing” information.

[The claim] requires nothing more than collecting information (water clarity and light transmittance) and analyzing that information (by applying the chart included in the claim), which collectively amount to the abstract idea of selecting a fishing hook based on the observed water conditions.

Id.

The inventor’s brief explains that the fish are able to make the same color selection, and the process here apparently mimics their color selection preferences. On appeal, the Federal Circuit found that piscatory mental processes tend to suggest that the invention is unpatentable.

While we decline today to adopt a bright-line test that mental processes capable of being performed by fish are not patent eligible, this observation underscores our conclusion that claim 34 is directed to the abstract idea of selecting the color of a fishing hook.

Id. The court does not offer an explanation for its conclusion other than a cite to Elec. Power Grp. (statements regarding human mental processes). Perhaps a cite to Enfish, LLC v. Microsoft Corp., 822 F.3d 1327 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

The court suggested that the claimed method might become patent eligible if the measurement techniques were limited to a particular method or instrumentality. “Because the claims before us are not limited in the way Mr. Rudy suggests, we are not in a position to opine on whether theoretical claims that were so limited would be patent eligible.”

Here, the court repeated its prior statements that the PTO guidance on patent eligibility does not bind or limit the Federal Circuit in any way. “To the extent the Office Guidance contradicts or does not fully accord with our caselaw, it is our caselaw, and the Supreme Court precedent it is based upon, that must control.”

Rudy also envoked the machine-or-transformation test — referring to the fact that the fish was originally free but was then caught. On appeal, the Federal Circuit confirmed that the test remaines a “useful and important clue” to eligibility. However, the claim here does not require actually catching a fish. Rather, as Rudy explained in his own briefing: “Landing a fish is never a sure thing. Many an angler has gone fishing and returned empty handed.” Perhaps the adage here should replace “angler” with “appellant.” No Patent for Rudy (Yet).

Patently-O Bits and Bytes by Juvan Bonni

Recent Headlines in the IP World:

- Dr. Jonathan Gluckman: Sixth Wave Expands Virus Detection Patent Applications (Source: Yahoo Finance)

- Chris Burt: Large-Area Under-Display Biometric Fingerprint Sensing Shown in Apple Patent Application (Source: Biometric Update)

- Will Heasman: China Dominates Global Blockchain Patent Applications (Source: Decrypt)

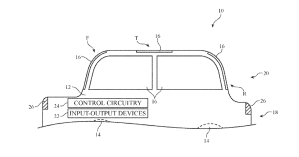

- William Gallagher: Apple Car Could Have Automatically Tinting ‘Moon Foof’ and Windows (Source: Apple Insider)

Commentary and Journal Articles:

- Wendy J. Gordon: Asymmetric Market Failure and Prisoner’s Dilemma in Intellectual Property (Source: SSRN)

- Dr. Gaétan de Rassenfosse and Kyle Higham: Wanted: A Standard for Virtual Patent Marking (Source: SSRN)

- Prof. Ernst-Ulrich Petersmann: International Settlement of Trade and Investment Disputes Over Chinese ‘Silk Road Projects’ Inside the European Union (Source: SSRN)

New Job Postings on Patently-O:

Disgorgement of Infringer Profits as an Equitable Remedy

Guest Post by Prof. Pamela Samuelson.

Yesterday, Dennis Crouch provided an overview of the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Romag Fasteners, Inc. v. Fossil, Inc. and the various opinions of the Justices.

Today I consider the implications of Romag for whether juries or only judges can decide about disgorgement of a trademark infringer’s profits in trademark cases. None of the Justices addressed that issue directly. Yet, the majority opinion repeatedly characterized disgorgement of profits as an equitable remedy and emphasized transsubstantive principles of equity as lodestones for the exercise of equitable discretion in granting this remedy. Because of this, I believe the Court implicitly decided that disgorgement is a matter for courts, and not for juries, to decide. This has very important implications for disgorgement awards in intellectual property (IP) cases more generally.

This implicit ruling in Romag is consistent with the Court’s ruling in Petrella

v. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., 572 US. 663 (2014). Although holding that laches was not a complete defense to copyright infringement, the Court in Petrella stated that disgorgement was an equitable remedy. Id. at 668 n.1. It opined that “the District Court, in determining appropriate injunctive relief and assessing profits, may take account of [Petrella’s] delay in commencing suit. In doing so, however, that court should closely examine MGM’s alleged reliance on Petrella’s delay.” Id. at 687. The Court was, moreover, receptive to “any other considerations that would justify adjusting injunctive relief or profits.” Id. at 687-88.

Unfortunately, the Court failed to acknowledge disgorgement as an equitable remedy in Samsung Electronics Co. v. Apple, Inc., 137 S.Ct. 429 (2016) or to invoke equitable principles as relevant considerations in awarding disgorgement in design patent cases. The Solicitor General’s brief in Samsung contemplated that juries would make disgorgement awards and offered a complex (and deeply flawed) multi-factor test for deciding whether the relevant article of manufacture whose profits must be disgorged was the end product (e.g., smartphones) or only some part of it (e.g., rounded corners with bezel).

Who knows what Judge Koh would have ordered had she ruled on how much of Samsung’s profits should be disgorged for infringement of three small Apple design patents? It is, however, unlikely that she would have settled on $533 million, the amount that the jury awarded on remand, given that she had previously reduced a $1.05 billion total-profit-on-end-products jury award to $399 million. This is the amount that the Court vacated in Samsung because the lower courts had wrongly held that all profits on end products must be disgorged.

That disgorgement is an equitable remedy that only judges can order in an IP case was further recognized in Texas Optoelectronic Solutions, Inc. v. Renesas Elecs. Am., Inc., 895 F.3d 1304 (Fed. Cir. 2018). In this state law trade secrecy case, the Federal Circuit vacated a jury’s disgorgement award of $48.8 million on the ground that it was improper for juries to award an equitable remedy. The court reviewed at length the historical record of the disgorgement remedy in IP cases. Id. at 1319-25. It cited the Court’s decision in Sheldon v. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures Corp., 309 U.S. 390, 399 (1940) for the proposition that “recovery of profits … had been allowed in equity both in copyright and patent cases as appropriate equitable relief incident to a decree for an injunction.” Id. at 1324. Had the Federal Circuit recognized this principle a few years before, it would have been Judge Koh, not a jury, who would have decided how much of Samsung’s profits should be disgorged.

Petrella notwithstanding, only one copyright decision has thus far ruled that the award of infringer profits is a matter for judicial discretion, not for juries. See

Fair Isaac Corp. v. Fed. Ins. Co., 2019 WL 5057865 (D. Minn. 2019) (disgorgement of profits held an equitable remedy for which a jury award was unavailable in a software copyright infringement case).

Romag is not the only trademark decision to have reserved disgorgement awards to the discretion of judges. A number of trademark cases have ruled that only judges, not juries, can render disgorgement awards. See Hard Candy LLC v. Anastasia Beverly Hills, 921 F.3d 1343, 1355-59 (11th Cir. 2019) (denying trademark plaintiff’s demand for a jury trial on its disgorgement claim); Fifty-Six Hope Rd. Music, Ltd. v. A.V.E.L.A., Inc., 778 F.3d 1059, 1074–76 (9th Cir. 2015).

In a forthcoming article, colleagues and I point out that traditional principles of restitution and unjust enrichment support awards of disgorgement of profits insofar as they are (1) levied against conscious wrongdoers, (2) attributable to the wrongful conduct, and (3) subject to equitable discretion. Justice Sotomayor’s concurrence in Romag rightly noted that innocent or good faith infringers should not have to disgorge profits because the goal of this remedy is to ensure that conscious wrongdoers do not profit from their misdeeds. Insofar as the majority opinion in Romag contemplated that profits of innocent trademark infringers could be disgorged, it is at odds with traditional equitable principles. In Romag, both laches and inequitable conduct should preclude profits disgorgement upon remand. For a further elaboration on this point and about equitable discretion in IP disgorgement cases more generally, see Pamela Samuelson, John M. Golden, & Mark P. Gergen, Recalibrating Disgorgement Awards in Intellectual Property Cases, B.U. L. Rev. (forthcoming 2021), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3529750.

Profit Disgorgement Allowed in TM Cases Without Showing Willfulness

Will the Court Correct the Mess that is GS CleanTech Corp. v. Adkins Energy LLC?

by David Hricik, Mercer Law School

In my earlier post, I noted some of the clear errors in the panel decision in GS CleanTech Corp. and Cantor Colburn LLP v. Adkins Energy LLC (Fed. Cir. 2020) . The patentee has filed for rehearing en banc, and the petition is here. I wish I had time to write an amicus brief in support, but after giving a CLE today about the case (here is link but you have to buy it, I think) and reading that brief, I believe the problems with the case run far deeper than I originally thought and even deeper than that brief points out.

Here’s why.

When inequitable conduct is asserted, often it is bifurcated from validity/infringement. Where either a jury finds invalidity, or as in CleanTech the judge did on summary judgment, and that finding is based upon allegedly withheld art, the patent owner will need to appeal (to avoid CleanTech). But, there is, under those circumstances, no final judgment.

Nor will any judgment fall within any exception — at least not very often. The patentee likely won’t be able to seek appeal under Fed. R. Civ. P. 54(b), because it only applies if there are multiple claims or multiple parties, so in a single-patent-single-defendant case, it wouldn’t likely be available. While possibly a trial court could certify a case for appeal under 1292(b), that requires there be a controlling question of law and substantial ground for disagreement, that won’t often be the case and the Federal Circuit has to also agree to certification. The collateral order exception won’t apply because the order won’t be separate from the merits. Any judgment will not (unless a preliminary injunction was granted and then dissolved because of an invalidity finding) grant or deny, an injunction (it will decide no liability and that’s not the same as denial of an injunction). Mandamus won’t be available.

So, the appeal will be from the judgment entered after the inequitable conduct trial. The CleanTech case held that “abuse of discretion” applies to review of inequitable conduct — to the findings of materiality (even though in CleanTech it was a question of law based on underlying facts), to the fact findings of knowledge of materiality, and to the finding of intent to deceive. Standard of appellate review on materiality will be much looser than if validity had been appealed, in other words. The standards of review for knowledge of materiality and of intent will be looser than TheraSense, too.

But it gets worse if summary judgment was the basis for invalidity (and, so, materiality).

On appeal of summary judgment, facts are viewed in the light most favorable to the non-moving party and all reasonable inferences are taken in the non-movant’s favor. So, in CleanTech the panel should have, without deference to the trial court, asked whether there was no genuine issue of disputed fact and no reasonable jury could find other than, by clear and convincing evidence, there had been an offer to sale (and not an experimental one) that invalidated a claim. Under the panel decision, instead, the question is whether the district court abused its discretion in making that determination.

None of that makes sense.

But what does make sense is that any litigator representing a patentee who loses on invalidity must do whatever is reasonably possible to appeal because otherwise the CleanTech approach will apply. And, of course, it will permit creative defense lawyers to argue to trial courts that (somehow) determining the propriety of summary judgment is not conducted as the Supreme Court has repeated admonished (most recently in Tolan v. Cotton).

I hope the full court realizes the panel decision — whether the result is right or not — is from a procedural view irreconcilable with Therasense and settled standards of review, and, further, will result in efforts to try piecemeal appeals that will waste judicial resources and, if uncorrected, lead to improper findings of inequitable conduct.

Profit Disgorgement Allowed in TM Cases Without Showing Willfulness

by Dennis Crouch

Romag Fasteners, Inc. v. Fossil Group, Inc. (Supreme Court 2020)

The Lanham Act provides that a trademark owner can elect disgorgement of the defendant’s profits based upon “a violation under §1125(a) or (d) … or a willful violation under section 1125(c).”

- §1125(a) – TM infringement (likelihood of confusion)

- §1125(c) Dilution

- §1125(d) Cybersquatting

15 U.S.C. §1117(a). The statute appears to require willfulness as a prerequisite to profit disgorgement in the dilution context, but not for typical trademark infringement. However, the award must also conform “to the principles of equity.”

In this case, Romag proved its §1125(a) TM infringement case against Fossil, but the District Court refused to disgorge profits — holding that willfulness is a prerequisite to profit disgorgement in TM cases based upon a long line of pre-and-post Lanham Act decisions. The Federal Circuit then affirmed.

The Supreme Court has now reversed course, holding that a district court may award the plaintiff with “the defendant’s ill-gotten profits” even without a showing of willfulness. However, the court does not go so far as to say plainly that a winning plaintiff “is entitled . . . to recover (1) defendant’s profits.” Rather, the court takes a somewhat middle-road — holding that the principles of equity indicate that an infringer’s mens rea (mental state) is “a highly important consideration in determining whether an award of profits is appropriate.” However, the mental state consideration does not require an “inflexible precondition” of willfulness.

The majority opinion is authored by Justice Gorsuch and joined by seven (7) other justices. Justice Alito joined the majority but also wrote a concurring opinion joined by Justices Breyer and Kagan. Justice Sotomayor also concurred.

The two concurring opinions appear written to attempt to clarify some internal inconsistencies within the Gorsuch opinion. The Alito concurrence is only 1 paragraph and appears written to reemphasize the holding that willfulness is a highly important consideration:

The decision below held that willfulness is such a prerequisite. That is incorrect. The relevant authorities, particularly pre-Lanham Act case law, show that willfulness is a highly important consideration in awarding profits under §1117(a), but not an absolute precondition.

Alito concurring.

Justice Sotomayor further explains that the majority “suggests that courts of equity were just as likely to award profits for such ‘willful’ infringement as they were for ‘innocent’ infringement.” Justice Sotomayor explains that the majority’s statement “does not reflect the weight of authority, which indicates that profits were hardly, if ever, awarded for innocent infringement.” The concurring opinion also points to a feature of possible confusion – that the willfulness definition was formerly more broadly defined to include a “range of culpable mental states–including the equivalent of recklessness.”

I will note that IP Remedies Professor Thomas Cotter has posted a short note about the opinion with the following to-the-point statement: “To say I am disgusted would be an understatement.” Prof. Cotter recalls that the Patent Statute also doesn’t say anything about willfulness, but that the Supreme Court recently reaffirmed that willfulness is a requirement for enhanced damages under Section 284 (“the court may increase the damages up to three times the amount found or assessed.”).

Adjusting to Alice: USPTO patent examination outcomes after Alice Corp v. CLS Bank International

The chart above comes from the USPTO Chief Economist’s office and is explained in the USPTO’s new report on Post-Alice Examination of Eligibility.

Cancelling Pre-AIA patents and the Takings Clause

Guest Post by Prof. Gregory Dolin (Baltimore). Prof. Dolin recently filed an amicus brief supporting Celgene’s arguments that AIA post-issuance review represents an uncompensated takings of pre-AIA patent rights.

Since its passage in 2011, the America Invents Act has been subject to numerous Supreme Court decisions. But thus far, the major constitutional challenge to the Act in Oil States Energy Servs v. Greene’s Energy Group has failed. But while the Court the, upheld the AIA’s post-issuance review system against an Article III challenge, left a major question open. The Oil States Court stated that it was not resolving whether the application the AIA-created procedures to patents issued prior to the AIA’s effective date violates the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment. This question is now squarely presented to the Court in Celgene v. Peter. (There are also pending cases that in addition to the Takings issue raise a Due Process challenge).

Celgene owns two patents “generally directed to methods for safely distributing teratogenic or other potentially hazardous drugs while avoiding exposure to a fetus to avoid adverse side effects of the drug.” These patents were issued in 2000 and 2001, or more than a decade prior to the enactment of the AIA. These patents were challenged before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) in 2015 in an Inter Partes Review (IPR), and the proceeding resulted in cancellation of all but one of the challenged claims in both patents. As with other post-issuance proceedings, but unlike district court litigation, Celgene’s patents enjoyed no presumption of validity, and could be cancelled upon preponderance of evidence. Furthermore, in construing Celgene’s claims, PTAB utilized the “broadest reasonable interpretation” (BRI) approach, as was called for by the then-current rules. The interplay of lower standard of proof for cancellation and the BRI standard, combined with the lack of a meaningful opportunity to amend the claims, left patents challenged in IPR particularly vulnerable. (Since that time, the Patent Office issued new rules to amend its procedures and now measures the claims under the Phillips framework—the same standard in use by Article III tribunals).

Celgene challenged this procedure in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, arguing that by applying a different claim construction standard than in district court and denying the patent a previously existent presumption of validity, the America Invents Act retroactively devalued its property rights in their patents and therefore resulted in the constitutionally compensable Taking in violation of the Fifth Amendment. Relying on its two prior decisions, the Federal Circuit rejected the argument, holding that the presumption of validity is not “a property right subject to the protection of the Constitution.” Additionally, the Federal Circuit held that Celgene suffered no diminution in its property rights because its patents were always subject to ex parte and inter partes reexamination proceedings, both of which use (or used) the preponderance of the evidence standard with respect to patent validity. Celgene sought certiorari and I, together with Professors Kristen Jakobsen Osenga and Irina Manta filed a brief in support of the petition.

The argument we made in favor of Celgene is relatively straightforward. As the Supreme Court recognized time and again, a patent is a property right protected by the Takings Clause of the Constitution. In turn, the decision to procure a patent is fundamentally an investment decision which takes into account the likelihood that a patent would be challenged and survive such a challenge. In addition, the decision to disclose the invention and forgo trade secret protection is essentially a tradeoff: the patentee sacrifices the confidentiality of the invention in exchange for the protections of the patent system. (Admittedly, it is not always possible to keep the invention secret, especially if regulatory approval is necessary as in the case of Food and Drug Administration’s approval to market drugs or medical devices. Nonetheless, broadly speaking, an inventor has a choice between patent protection and trade secrecy protection). Depending on the robustness of those protections, the scales of the decision on whether to seek a patent may tip one way or another. Thus, the legal regime existing at the time the applicant filed for the patent constitutes the patentee’s “investment-backed expectation.”

The legal regime matters, and IPRs couldn’t be more different from reexaminations. As my research shows, the economic impact of the AIA on patent holders has been profound. The reason behind this significant drop in value is that although administrative review procedures have existed for nearly 40 years, these procedures have always been coupled with a patentee’s unlimited right to amend the claims in order to preserve their validity. Thus, prior to the AIA the patentee knew that if his patent were challenged one of two things will happen. One option was for the dispute to end up in an Article III court where the claim would rise and fall as written, but where the patent would enjoy a presumption of validity. Alternatively, the dispute would be resolved by the Patent Office where the claims would not be presumed valid, but would be subject to amendments for as long as the patentee was willing to continue prosecuting the patent. The AIA fundamentally altered this balance. Under the AIA, claim patentability can be adjudicated by the PTAB without the presumption of validity and without a robust opportunity to amend the claims. (Although the statute does permit claim amendments, these are not as of right, but must be requested by motion to the PTAB. Since October 2017 when the Federal Circuit held that Motions to Amend must be allowed unless the Patent Office carried its burden to show that claims are unpatentable, the PTAB has granted only 16% of such motions (with an additional 6.5% being granted in part). These already low numbers are a significant improvement from the pre-2017 system where the PTAB granted under 3% of such motions.

It should be acknowledged that Celgene did not seek to amend its claims during the PTAB proceedings, which may make it not an ideal vehicle to resolve the takings claim. On the other hand, given PTAB’s rejectionist approach to motions to amend, it is quite possible that Celgene was among countless patentees who chose not to bother with filing the motions in the first place. (It is worth noting that Celgene’s patents were adjudicated prior to October 2017).

The Supreme Court has previously concluded in Ruckelshaus v. Monsanto Co., that when the government changes the terms of the bargain with an individual, such a change can result in a regulatory taking. In Monsanto, the Court held that the Environmental Protection Agency’s public disclosure of data voluntarily submitted to the Agency may, in some circumstances, constitute a taking. The Court’s analysis was centered on the legal rules governing the use and disclosure of such data and the “nature of the expectations of the submitter at the time the data were submitted.” The Court held that the Government’s guarantee at the time of submission that the submitted data would remain a trade secret and not be disclosed to third parties “formed the basis of a reasonable investment-backed expectation” and played a role in the property holder’s decision whether to submit the data to the EPA in the first place. Celgene’s situation is analogous. When it had to make a decision whether or not to obtain a patent or rely on trade secrecy, it made the decision by reference to the then existing government guarantees of patent protections. Changes to that regime are what constitutes a compensable taking.

Before closing, it should be acknowledged that there is a significant issue that is antecedent to the question presented in Celgene’s petition. That is whether the Federal Circuit has jurisdiction to hear such claims absent filing of a claim for compensation in the Court of Federal Claims (CFC) and if so, how the Claims Court is supposed to evaluate the value of property lost. That question is embedded in a separate petition before the Supreme Court. The Federal Circuit has recently concluded that the CFC does have jurisdiction to hear such claims, even if on the merits it must reject them. The Government has advanced a contrary view (which the CFC endorsed, though this endorsement is at odds with the Federal Circuit’s later opinion). It may be that this issue may need to be resolved before (or concurrently with) the issue presented by Celgene.

In sum, the Supreme Court should answer the question whether retroactive application of the AIA’s post issuance review procedures to patents issued prior to the passage of the AIA, and which results in their invalidation, constitutes a taking within the meaning of the Fifth Amendment—a question the Court explicitly left open in Oil States. And in my view, the answer should be “yes.”

Judge Stoll Calls for En Banc Consideration of Assignor Estoppel

by Dennis Crouch

Hologic, Inc. v. Minerva Surgical, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2020)

The assignor estoppel doctrine (a doctrine in equity) potentially becomes more important in times of economic upheaval. Through layoffs, mergers, and acquisition of underperforming companies, patents are more likely to end up in the hands of someone other than their original owner or assignee. Conflicts then arise when that original inventor (or prior owner) reenters the market and begins to compete against the new patent owner. The doctrine of assignor estoppel operates to bar the original inventory from later challenging the validity of the patent. An oddity of Federal Circuit precedent though, is that assignor estoppel does not apply to USPTO IPR Actions.

In its decision here, the Federal Circuit reluctantly enforced the assignor estoppel doctrine noting that the court is “bound to follow” its prior precedent. Judge Stoll penned the opinion that was joined by both Judge Wallach and Judge Clevenger. Judge Stoll also filed a set of “additional views” suggesting that “it is time for this court to consider en banc the doctrine of assignor estoppel at it applies both in district court and in the Patent Office.”

We should seek to clarify this odd and seemingly illogical regime in which an assignor cannot present any invalidity defenses in district court but can present a limited set of invalidity grounds in an IPR proceeding.

Slip Op. Additional Views by Judge Judge Stoll.

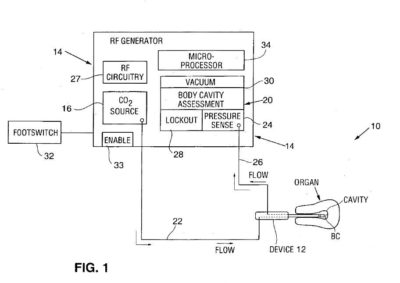

Hologic v. Minerva centers on the work of inventor and entrepreneur Csaba Truckai and relates to a medical device for detecting uterine perforations. The basic idea is that the device pumps gas into the uterus and then measures the pressure for a few minutes to see if gas has leaked-out. U.S. Patent Nos. 6,872,183 and 9,095,348.

This is a bit of a tale: Back in the 1990’s Truckai invented and assigned rights to his company NovaCept. NovaCept was later acquired by Cytec Corp. and then Hologic acquired Cytec. Truckai was still around for those buyouts and made a substantial amount of money. Meanwhile, Truckai left the company in 2008 and founded a new company Minerva that now competes with Hologic.

When Hologic sued Minerva, the defendant responded with several invalidity defenses and also petitioned the PTAB for inter partes review of the two patents. For its part, the Board granted review of the ‘183 patent and found the claims unpatentable as obvious. The Board denied review of the ‘348 patent.

Meanwhile, the district court case continued with the district court judge applying assignor estoppel to prevent Minerva from asserting invalidity defenses in district court — holding that “Truckai is in privity with Minerva.” A jury then sided with the patentee and awarded $5 million in damages for the two patents. Although the ‘183 patent had been cancelled in the IPR, the District Court judge did not give the PTAB judgment any preclusive effect because that issue was then on appeal. Subsequently, the Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s cancellation of the ‘183 patent claims.

When the ‘183 patent was finally invalidated by the Federal Circuit, the district court looked back at the jury verdict, but decided to enforce the verdict — holding that “jury’s damages determination can be adequately supported by the finding of infringement of Claim 1 of the [still valid] ’348 patent.” The district court also held assignor estoppel prevented the Minerva from applying the PTAB cancellation to the district court decision. The district court wrote: “the final outcome of the IPR is irrelevant to the district court proceeding . . . [t]o hold otherwise would be to hold that the [AIA] abrogated the assignor estoppel doctrine in a district court infringement action.”

On appeal, the Federal Circuit first rejected the district court’s clearly erroneous decision giving no effect to the PTAB cancellation (affirmed by the Federal Circuit). The court explained that the PTAB judgment renders the claims retroactively “void ab initio.” In an unusual statement, the court stated that it was “mindful of the seeming unfairness to Hologic in this situation.” The apparent unfairness is that the company will not be able to enforce a patent that has been invalidated.

For the remaining ‘348 patent, the defendant Minerva asked the court to “abandon the doctrine” entirely. Barring that, Minerva suggested that the doctrine should not apply to the ‘348 patent — which is a continuation of Truckai’s original patent filing with substantially broadened claims. The court resisted — holding that “equities weigh in favor of its application in this case.”

With regard to the expanded scope during prosecution, the Federal Circuit added a further quirk to the analysis by reviving a squib from some older cases: Westinghouse Electric & Mfg. Co. v. Formica Insulation Co., 266 U.S. 342 (1924) & Diamond Sci. Co. v. Ambico, Inc., 848 F.2d 1220 (Fed. Cir. 1988). In Diamond Sci., the Federal Circuit explained:

Westinghouse does allow for an accommodation in such circumstances. To the extent that Diamond may have broadened the claims in the patent applications (after the assignments) beyond what could be validly claimed in light of the prior art, Westinghouse may allow appellants to introduce evidence of prior art to narrow the scope of the claims of the patents, which may bring their accused devices outside the scope of the claims of the patents in suit. exception to assignor estoppel also shows that estopping appellants from raising invalidity defenses does not necessarily prevent them from successfully defending against Diamond’s infringement claims.

In Diamond Sci., the Federal Circuit was a little cagey on this right-to-narrow-claim-scope (“Westinghouse may allow . . . [the doctrine] does not necessarily prevent …”). Here, the court is more explicit: “[T]his court’s precedents allow Minerva to introduce evidence of prior art to narrow the scope of claim 1 so as to bring its accused product outside the scope of claim 1.” (internal quotes removed). The basic idea here is that an estopped party can avoid infringement by showing “that the accused devices are within the prior art and therefore cannot infringe.” Mentor Graphics Corp. v. Quickturn Design Sys., Inc., 150 F.3d 1374 (Fed. Cir. 1998) citing Scott Paper Co. v. Marcalus Mfg. Co., 326 U.S. 249 (1945). In his article on the topic, Prof. Mark Lemley suggests this narrowing-the-claim a “promise is likely illusory in modern patent jurisprudence, which has all but eliminated the ability to argue that claims should be narrowed to avoid invalidating prior art.”

= = = =

On damages, the jury was asked for the damages associated with infringing the two patents without requiring any patent-by-patent apportionment. Since one of the patents is invalid, you would think this would require a new trial on damages. However, the Federal Circuit has a big exception that allows the damages award to stand “if, despite the fact that some of the asserted claims were held invalid or not infringed subsequent to the award, undisputed evidence’ demonstrated that the sustained patent claim was necessarily infringed by all of the accused activity on which the damages award was based.” (citing Western Geco).

Here, the damages verdict is supported by the jury’s finding that the accused products all infringed Claim 1 of the still-valid ‘348 patent. This was further supported by the patentee’s damages expert who testified that the damages should be the same regardless of whether the jury finds infringement of one patent or both patents. Since “Minerva did not present any contrary evidence,” any error in jury instruction is deemed harmless.

Attorney Fees Following PTAB Invalidation

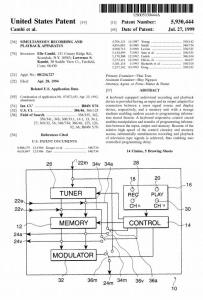

Dragon Intellectual Property, LLC v. Dish Network LLC (Fed. Cir. 2020)

After Dragon sued DISH for patent infringement back in 2013, DISH collaterally attacked the patent with an inter partes review (IPR) proceeding against the asserted US5930444. The district court partially stayed the litigation — stayed as to DISH and another IPR filer (SXM), but continued the litigation proceedings as to eight other defendants.

Things didn’t go so well for Dragon. Following a claim construction, the district court entered judgment of non-infringement in favor of all defendants (April 2016). Then, the PTAB came back cancelling all of the asserted claims (June 2016). On appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB cancellation and dismissed the district court appeal as moot. On remand, the district court then vacated its prior non-infringement decision and also dismissed the case as moot under US Bancorp and Munsingwear. “A party who seeks review of the merits of an adverse ruling, but is frustrated by the vagaries of circumstance, ought not in fairness be forced to acquiesce in the judgment” U.S. Bancorp Mortg. Co. v. Bonner Mall P’ship, 513 U.S. 18, 25 (1994).

Following the dismissal for mootness, DISH and SXM requested attorney fees under 35 U.S.C. § 285 as the prevailing parties. The district court denied the motion — finding that the parties won the case, but don’t actually count as “prevailing parties” as required by the statute.

The court in exceptional cases may award reasonable attorney fees to the prevailing party.

35 U.S.C. § 285. Further, the district court ruled that the success came in the PTAB, not the district court; and “success in a different forum is not a basis for attorneys’ fees.”

On appeal, the Federal Circuit has vacated and remanded — holding that the “prevailing party” question does not require “actual relief on the merits.” What matters is whether the defendant “successfully rebuffed Dragon’s attempt to alter the parties’ legal relationship in an infringement suit.”

For precedent here the court cites and follows B.E. Tech., L.L.C. v. Facebook, Inc., 940 F.3d 675 (Fed. Cir. 2019). B.E.Tech. has very similar facts with an infringement lawsuit being rendered moot based upon an unpatentability finding during an IPR. One difference is that in B.E.Tech, the defendant was seeking costs under Fed. R. Civ. P. 54(d)(1) rather than attorney fees under 35 U.S.C. § 285. However, since both provisions require a “prevailing party,” the court found that the the same rule should apply to both situations.

The decision here should be distinguished from the court’s recent decision in O.F. Mossberg & Sons, Inc. v. Timney Triggers, LLC, 2019-1134, 2020 WL 1845302, at *3 (Fed. Cir. Apr. 13, 2020). In Mossberg, the court ruled that case voluntarily dismissed without a court order could not satisfy the prevailing party requirement because it lacked “sufficient judicial imprimatur.”

On remand in Dragon IP, the district court will need to reconsider whether an exceptional case exists and whether attorney fees are appropriate given that the defendant now satisfies the “prevailing party” requirement.

Of note, although the mootness determination satisfies the prevailing party requirement, it is likely not sufficiently “on the merits” in order to satisfy the requirements for claim or issue preclusion.

SCT: Procedural Rules Should Not Unwind the Power of IPR’s to Cancel Bad Patents

by Dennis Crouch

Thryv, Inc. v. Click-to-Call Tech (Supreme Court 2020)

In this case, the Supreme Court has sided with the PTO and Patent-Challengers — holding that the agency’s decision to hear an IPR challenge is not reviewable on appeal — even if the challenge is based upon the time-bar of §315(b). According to the court, a ruling otherwise “unwind the agency’s merits decision” and “operate to save bad patent claims.”

Read the Decision Here: https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/19pdf/18-916_f2ah.pdf

The statutes authorizing inter partes review proceedings (IPRs) provides the USPTO Director with substantial latitude in determining whether or not to grant initiate an IPR. One limitation is that an IPR petition must be filed within 1-year of the petitioner (or privy) being served with a complaint fo infringing the patent. 35 U.S.C. §315(b). The PTO cancelled Click-to-Call’s patent claims, but the Federal Circuit vacated that judgment after holding that the PTO should not have initated the IPR. The issue on appeal was whether a lawsuit that had been dismissed without prejudice still counted under the §315(b) time-bar. No, according to the PTO; Yes, according to the Federal Circuit.

A key problem with the Federal Circuit’s decision is the no-appeal provision also found in the statute:

The determination by the Director whether to institute an inter partes review under this section shall be final and nonappealable.

35 U.S.C. §314(d). The Federal Circuit held that the time-bar issue should be seen as an exception to the statute, the Supreme Court though has rejected that analysis.

Cuozzo: This is the Supreme Court’s second venture into analysis of the time-bar. In Cuozzo Speed Techs., LLC v. Lee, 136 S. Ct. 2131 (2016), the court held that the no-appeal provision will preclude appellate review in cases “where the grounds for attacking the decision to institute inter partes review consist of questions that are closely tied to the application and interpretation of statutes related to the Patent Office’s decision to initiate inter partes review.” Cuozzo expressly did not decide when you might find exceptions — “we need not, and do not, decide the precise effect of § 314(d) on appeals that implicate constitutional questions, that depend on other less closely related statutes, or that present other questions of interpretation that reach, in terms of scope and impact, well beyond ‘this section.'”

In Thryv, the Supreme Court found that Cuozzo governs the time-bar question — holding that the statutory time-bar is closely related to the institution decision:

Section 315(b)’s time limitation is integral to, indeed a condition on, institution. After all, §315(b) sets forth a circumstance in which “[a]n inter partes review may not be instituted.” Even Click-to-Call and the Court of Appeals recognize that §315(b) governs institution.

Majority Op. “The appeal bar, we … reiterate, is not limited to the agency’s application of §314(a).” Id. at n.6.

In its decision, the Supreme Court also puts its thumb on the policy concerns of “overpatenting” and efficiently “weed[ing] out bad patent claims.”

Allowing §315(b) appeals would tug against that objective, wasting the resources spent resolving patentability and leaving bad patents enforceable. A successful §315(b) appeal would terminate in vacatur of the agency’s decision; in lieu of enabling judicial review of patentability, vacatur would unwind the agency’s merits decision. And because a patent owner would need to appeal on §315(b) untimeliness grounds only if she could not prevail on patentability, §315(b) appeals would operate to save bad patent claims. This case illustrates the dynamic. The agency held Click-to-Call’s patent claims invalid, and Click-to-Call does not contest that holding. It resists only the agency’s institution decision, mindful that if the institution decision is reversed, then the agency’s work will be undone and the canceled patent claims resurrected.

Majority Op. Section III.C

Justice Ginsburg delivered the opinion joined in fully by Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Breyer, Kagan, and Kavanaugh. Justices Thomas and Alito joined with the decision except for the policy statements found in III.C.

Justice Gorsuch wrote in dissent and was substantially joined by Justice Sotomayor. Justice Gorsuch was not yet on the court when Cuozzo was decided, and Justice Sotomayor joined Justice Alito’s dissent to that decision. The basics of the dissent is that our Constitution does not permit a “politically guided agency” to revoke property rights without judicial review:

Today the Court takes a flawed premise—that the Constitution permits a politically guided agency to revoke an inventor’s property right in an issued patent—and bends it further, allowing the agency’s decision to stand immune from judicial review. Worse, the Court closes the courthouse not in a case where the patent owner is merely unhappy with the merits of the agency’s decision but where the owner claims the agency’s proceedings were unlawful from the start. Most remarkably, the Court denies judicial review even though the government now concedes that the patent owner is right and this entire exercise in property taking-by-bureaucracy was forbidden by law.

Id. The majority reject’s the dissent’s call for patents-as-property:

The dissent acknowledges that “Congress authorized inter partes review to encourage further scrutiny of already issued patents.” Yet the dissent, despite the Court’s decision upholding the constitutionality of such review in Oil States Energy Services, LLC v. Greene’s Energy Group, LLC, 584 U. S. ___ (2018), appears ultimately to urge that Congress lacks authority to permit second looks. Patents are property, the dissent several times repeats, and Congress has no prerogative to allow “property-taking-by-bureaucracy.” But see Oil States, 584 U. S., at ___ (slip op., at 7) (“patents are public franchises”). The second look Congress put in place is assigned to the very same bureaucracy that granted the patent in the first place. Why should that bureaucracy be trusted to give an honest count on first view, but a jaundiced one on second look?

Majority Op. at n.4.

In a portion of the dissent not signed by Justice Sotomayor, Justice Gorsuch laments that the majority decision “takes us further down the road of handing over judicial powers involving the disposition of individual rights to executive agency officials.”

So what if patents were, for centuries, regarded as a form of personal property that, like any other, could be taken only by a judgment of a court of law. So what if our separation of powers and history frown on unfettered executive power over individuals, their liberty, and their property. What the government gives, the government may take away—with or without the involvement of the independent Judiciary. Today, a majority compounds that error by abandoning a good part of what little judicial review even the AIA left behind.

Justice Gorsuch in Dissent – Part V.

Just try to imagine this Court treating other individual liberties or forms of private property this way. Major portions of this country were settled by homesteaders who moved west on the promise of land patents from the federal government. Much like an inventor seeking a patent for his invention, settlers seeking these governmental grants had to satisfy a number of conditions. But once a patent issued, the granted lands became the recipient’s private property, a vested right that could be withdrawn only in a court of law. No one thinks we would allow a bureaucracy in Washington to “cancel” a citizen’s right to his farm, and do so despite the government’s admission that it acted in violation of the very statute that gave it this supposed authority. For most of this Nation’s history it was thought an invention patent holder “holds a property in his invention by as good a title as the farmer holds his farm and flock.” Hovey v. Henry, 12 F. Cas. 603, 604 (No. 6,742) (CC Mass. 1846) (Woodbury, J., for the court). Yet now inventors hold nothing for long without executive grace. An issued patent becomes nothing more than a transfer slip from one agency window to another.

Id.

Patently-O Bits and Bytes by Juvan Bonni

Recent Headlines in the IP World:

- Stephanie Nebehay: In a First, China Knocks U.S. From Top Spot in Global Patent Race (Source: Reuters)

- Mohammad Musharraf: Sony and Other Major Multinationals File 212 Blockchain Patents in China in 2020 (Source: Coin Telegraph)

- Atty. Rebeca Harasimowicz: The Global Patent Race for a COVID-19 Vaccine (Source: The National Law Review)

- Ben Gilbert: Sony’s PlayStation Group Applies for Patent of a Robot Friend Who Will Play Games and Watch Movies with You (Source: Business Insider)

Commentary and Journal Articles:

- Scott Duke Kominers: Patent Protection Should Take a Backseat in a Crisis (Source: Bloomberg)

- Prof. Christopher Buccafusco and Prof. Jonathan S. Masur: Drugs, Patents, and Well-Being (Source: SSRN)

- Prof. Robert Burrell and Dr. Catherine Kelly: The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Challenge for Innovation Policy (Source: SSRN)

- Dr. Robert Farley: The F-35 and its IP Issues (Source: Lawyers, Guns, & Money)

New Job Postings on Patently-O:

CardioNet v. InfoBionic: Patenting a Diagnostic Tool

by Dennis Crouch

CardioNet, LLC v. InfoBionic, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2020)

I have been following this case for the past couple of years because it served as the template for our 8th Annual Patent Law Moot Court at Mizzou back in 2018 (Sponsored by McKool Smith).

In the case, CardioNet sued InfoBionic for infringement (D.Mass.). The district court quickly dismissed the case for failure to state a claim under R. 12(b)(6) – ruling that the claims of CardioNet’s US7941207 are improperly directed at patent-ineligible concepts under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

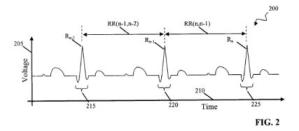

The ‘207 patent covers a method for identifying AF (atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter) that is associated with stroke, congestive heart failure, and cardiomyopathy. The invention particularly monitors heartbeat variability, including identification of irregular “ventricular beats.” The claims here use off-the-shelf technology to measure heartbeat activity and already existing logic for determining heartbeat variability. The new feature is claimed as “relevance determination logic to identify a relevance of the variability in the beat-to-beat timing to at least one of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter” and an “event generator” triggered when variability is “relevant.” Claim 1 is included below. (Some patent attorneys will point out that that the combination as a whole is also new).

The district court found that the claimed invention completely flows from the unpatentable idea that AF “can be distinguished by focusing on the variability of the irregular heartbeat.” As such, the claims were deemed invalid.

On appeal, a 2-1 majority has reversed – holding “instead that the asserted claims of the ’207 patent are directed to a patent-eligible improvement to cardiac monitoring technology and are not directed to an abstract idea.” In making this determination, the court looked to the claim language requirements and also

In particular, the language of claim 1 indicates that it is directed to a device that detects beat-to-beat timing of cardiac activity, detects premature ventricular beats, and determines the relevance of the beat-to-beat timing to atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter, taking into account the variability in the beat-to-beat timing caused by premature ventricular beats identified by the device’s ventricular beat detector. In our view, the claims “focus on a specific means or method that improves” cardiac monitoring technology; they are not “directed to a result or effect that itself is the abstract idea and merely invoke generic processes and machinery.” McRO.

Majority Op. The majority opinion was written by Judge Stoll and joined by Judge Plager. Judge Dyk concurred in judgment, but dissented from the majority reasoning.

This is a routine case easily resolved by existing precedent. Under that approach, I agree with the majority that the claims have not been shown to be patent ineligible under section 101. I dissent in part because the majority addresses issues never argued by the parties and appears to suggest approaches not consistent with Supreme Court and circuit authority.

Judge Dyk particularly takes issue with the majority’s statements that:

Step one of the Alice framework does not require an evaluation of the prior art or facts outside of the intrinsic record regarding the state of the art at the time of the invention. . . . [Although it] is within the trial court’s discretion whether to take judicial notice of a longstanding practice where there is no evidence of such practice in the intrinsic record. But there is no basis for requiring, as a matter of law, consideration of the prior art in the step one analysis in every case. If the extrinsic evidence is overwhelming to the point of being indisputable, then a court could take notice of that and find the claims directed to the abstract idea of automating a fundamental practice—but the court is not required to engage in such an inquiry in every case.

Majority Op. at 22. Judge Dyk argues that instead that “limiting the use of extrinsic evidence to establish that a practice is longstanding would be inconsistent with authority. No case has ever said that the nature of a longstanding practice cannot be determined by looking at the prior art.”

= = = =

1. A device, comprising:

a beat detector to identify a beat-to-beat timing of cardiac activity;

a ventricular beat detector to identify ventricular beats in the cardiac activity;

variability determination logic to determine a variability in the beat-to-beat timing of a collection of beats;

relevance determination logic to identify a relevance of the variability in the beat-to-beat timing to at least one of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter; and

an event generator to generate an event when the variability in the beat-to-beat timing is identified as relevant to the at least one of atrial fibrillation

Federal Circuit’s Unique Preclusion Principle

I previously wrote about Chrimar’s petition for writ of certiorari on the Federal Circuit’s unique doctrine of retroactive revocation of final judgments. The basics are: Once affirmed on appeal, a PTAB decision cancelling patent claims will effectively reverse and vacate any prior judicial final decisions of liability and damages so long as some aspect of the prior infringement lawsuit is still pending (typically in the form of a pending appeal on other grounds).

Whether the Federal Circuit may apply a finality standard for patent cases that conflicts with the standard applied by this Court and all other circuit courts in non-patent cases.

The court’s approach was originally solidified in Fresenius USA, Inc. v. Baxter International, 721 F.3d 1330 (Fed. Cir. 2013). That decision is now one of the most cited Federal Circuit opinions of the past decade.

Now, three amicus briefs have been filed in support of the petition:

- US Inventor: The “Court’s Fresenius line of precedent … improperly usurps a procedural issue from the regional circuits.” [Brief]

- The Naples Roundtable: “The Federal Circuit’s self-coined “Fresenius/Simmons preclusion principle” is unique to patent law, is contrary to the preclusion principles of other circuits, and is contrary to the Restatement of Judgments. The Fresenius/Simmons preclusion principle undermines the finality of prior judicial judgments. Finality of judgments is critical to the purpose of the civil judicial system—namely, conclusively and effectively resolving disputes between parties. Finality is essential to provide closure and certainty to both litigants and society, and prevents waste of judicial resources. [Brief]

- National Small Business Ass’n, Center for Individual Freedom, and Conservatives for Property Rights, et al.: “When an issue is definitively resolved in a case and memorialized in a final judgment, that makes resolution of the issue final between the parties. The issue cannot not be relitigated even if another portion of the case, regarding different issues, gets reopened, as on remand after appeal. That is the law in all areas of U.S. law except for patent law in the Federal Circuit.” [Brief]

The arguments her have substantial legal merit. Two problems (1) the Supreme Court has a history of treating preclusion differently for patent law with the idea that courts should not enforce a patent after it has been found invalid; (2) in this case the patent claims have been found invalid — and so a win here for Chimar is simply about timing of judicial process and not about rewarding merit (unless you are of the opinion that PTAB wrongly invalidated the claims).

Google v. Oracle (Supreme Court 2020)

Google v. Oracle (Supreme Court 2020)

The Supreme Court has rescheduled oral arguments in this big Copyright case until Fall 2020. I have mentioned previously that this case was likely to be the biggest patent case of 2020 — even though no patent questions were raised in the petition. The basic question is when software is copyrightable — the focus here is particularly at the interface-level (the the naming-convention for Java function calls). In the case, Google also suggests that if the naming-convention is copyrightable that any copyright should be so “thin” that fair use would readily apply in most situations.

Case will now be argued in October or November 2020 with a decision likely in 2021.

En Banc Denied

The Federal Circuit today denied two en banc rehearing petitions:

- Amgen Inc. v. Amneal Pharmaceuticals LLC. This decision focused on merely-tangential exception to the the prosecution-history-estoppel limitation on the doctrine-of-equivalents. The question for the petition is whether the district court must first identify the “rationale underlying [a narrowing] amendment” before deciding that the amendment is not merely tangential to the equivalent in question.

- Mira Advanced Technology v. Microsoft Corporation. Whether the PTAB’s construction of the term “contact list” was “arbitrary and capricious.”

Summary Judgment, Eligibility, and Appeals

by Dennis Crouch

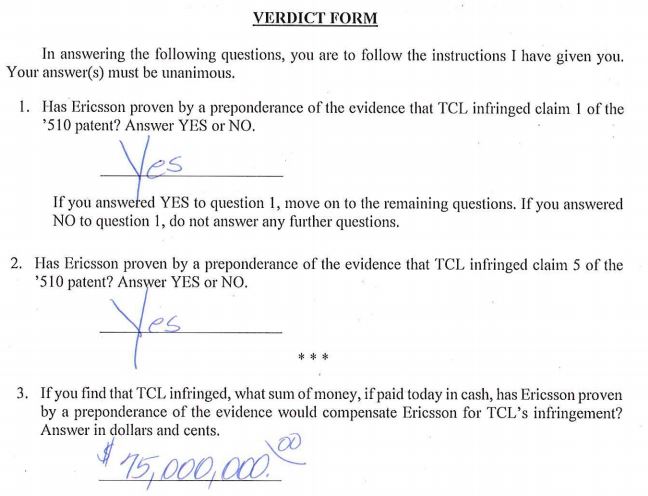

Ericsson Inc. v. TCL Communication Tech. (Fed. Cir. 2020)

The jury sided with Ericsson — holding that TCL willfully infringed the two asserted claims of Ericsson’s US7149510 and awarded $75 million in compensatory damages. Judge Payne then added an additional $25 million enhanced damages for the adjudged willfulness.

On appeal, a divided Federal Circuit has reversed judgment — holding that the asserted claims are actually invalid as a matter of law as being directed toward ineligible subject matter under Section 101. Majority Opinion by Chief Judge Prost and joined by Judge Chen. Dissenting Opinion by Judge Newman.

The bulk of the case focuses on waiver of TCL’s right to appeal – with the majority finding no waiver.

During the litigation, TCL moved for summary judgment of ineligibility. The district court denied that motion after finding that the patent was not directed toward an abstract idea. The case continued then continued to trial and judgment as noted above.

After being denied summary judgment, a moving party typically needs to take a couple of steps in order to preserve the argument for appeal. Preservation is necessary because the summary judgment motion is seen as effectively moot once trial starts, and so the party needs to make a post-trial renewed motion for Judgment as a Matter of Law (JMOL) under Fed. R. Civ. Pro. R.50(b) (or similar post-trial motion) in order to preserve the issue for appeal. And, under the rules, a R. 50(a) JMOL motion (made during trial) is a prerequisite to the post-trial R.50(b) renewed JMOL motion. An appeal can then follow if the judge denies the R.50(b) motion. Here, TCL did not file a JMOL motion or any other post-trial motion on eligibility, but instead simply appealed the Summary Judgment denial — typically a non-starter on appeal.

The waiver rule is different when Summary Judgment is granted. A grant of summary judgment finishes litigation on the issues decided, and those issues are fully preserved for appeal.

Coming back to this case: Many denials of summary judgment are based upon the existence disputed issues of material fact. And, even when a defendant’s SJ motion is denied, the defendant may still win the issue at trial. Here, however, when the district court denied the ineligibility SJ motion there was nothing left for the jury to decide. Using that logic, the majority held that when the court denied TCL’s ineligibility SJ motion, it effectively effectively granted SJ of eligibility. Critical to this determination is the appellate panel’s finding that “no party has raised a genuine fact issue that requires resolution.” With no facts to decide, the question became a pure issue of law: either it is eligibile or it is ineligible. “As a result, the district court effectively entered judgment of eligibility to Ericsson.” And, as I wrote above, a grant of summary judgment is appealable.

Writing in dissent, Judge Newman argues that the majority’s conclusion that pre-trial denial of SJ on eligibility is the same as a final decision going the other way “is not the general rule, and it is not the rule of the Fifth Circuit, whose procedural law controls this trial and appeal. . . . The majority announces new law and disrupts precedent.”

Judge Newman explained that TCL simply failed to pursue its Section 101 claim after Summary Judgment was denied.

TCL did not pursue any Section 101 aspect at the trial or in any post-trial proceeding. . . . TCL took no action to preserve the Section 101 issue, and Section 101 was not raised for decision and not mentioned in the district court’s final judgment.

There is no trial record and no evidence on the question of whether the claimed invention is an abstract idea and devoid of inventive content. The panel majority departs from the Federal Rules and from precedent.

Newman, J. in Dissent.

The majority also went on to say that its “authority is total” in deciding whether to hear an appeal because there is “no general rule.” “We have the discretion to hear issues that have been waived.” (The first quote is not actually from the court but something I read in the news). The court here oddly includes the following statements:

[T]here is “no general rule” for when we exercise our discretion to reach waived issues. . . . Our general rule against reaching waived issues is

based on sound policy. . . .

Majority opinion (concluding that if appeal was waived, the court would exercise its discretion to hear the appeal).

= = = =

On the merits of the invention, the majority and dissent also disagree. As you can read below, the claims are directed to a system for software-access-control and the majority found it directed to the “abstract idea of controlling access to, or limiting permission to, resources.” The district court instead found that the claims were directed to an “improved technological solution to mobile phone security software.”

1. A system for controlling access to a platform, the system comprising:

a platform having a software services component and an interface component, the interface component having at least one interface for providing access to the software services component for enabling application domain software to be installed, loaded, and run in the platform;

an access controller for controlling access to the software services component by a requesting application domain software via the at least one interface, the access controller comprising:

an interception module for receiving a request from the requesting application domain software to access the software services component;

and a decision entity for determining if the request should be granted wherein the decision entity is a security access manager, the security access manager holding access and permission policies; and

wherein the requesting application domain software is granted access to the software services component via the at least one interface if the request is granted.

5. The system according to claim 1, wherein:

the security access manager has a record of requesting application domain software;

and the security access manager determines if the request should be granted based on an identification stored in the record.