Search Results for: wireless

Chamberlain’s Garage Door Opener invalid as an Abstract Idea

Affinity II: Who Has the Burden for Alice Step II?

Cancellation of Progressive’s Business Method Patents Confirmed on Appeal

Bits and Bytes No. 101: Patent Bill & the Patent Lobby

Nonpracticing Entity (CSIRO) Gets Injunction

Sisvel v. Sierra Wireless – Useful Guidance for Prosecutors on Motivation to Combine and Means-Plus-Function Claims

Navigating Claim Construction and Broadening Amendments: Lessons from Sisvel v. Sierra Wireless

Broad Claims Bite Back: Drafting Narrower Scope in the Age of IPR

Is the Advance Meaningful?

A Nose of Wax and Splitting Hairs

“No License, No Problem” – Is Qualcomm’s Ninth Circuit Antitrust Victory a Patent Exhaustion Defeat?

Samsung Proposes a Patent Pledge to Settle EC FRAND Investigation

Technology Patents LLC. v. T-Mobile (UK) Ltd.

Patently-O Bits and Bytes No. 32: Patent Law Jobs

Patent Agent – Small Corporation – Carlsbad, Calif.

Metawave is a technology company that seeks to revolutionize the future of autonomous vehicles and wireless communications. Our team is engineering disruptive technologies for next-generation 5G communications and autonomous vehicle sensing. We are looking for a highly motivated, dynamic and collaborative patent agent for our beautiful headquarters in Carlsbad. This is an opportunity to be a part of a small and growing team of world-class leaders in the next generation wireless and autonomous vehicle sensing industries, who are at the leading edge of the next wave of RF millimeter wave hardware, wireless applications, artificial intelligence, object detection, and machine learning. Metawave was founded in the iconic PARC campus in the heart of Silicon Valley. Our Carlsbad office is in close walking distance to the beach and has a fun and lively SoCal, start-up atmosphere.

Metawave is a technology company that seeks to revolutionize the future of autonomous vehicles and wireless communications. Our team is engineering disruptive technologies for next-generation 5G communications and autonomous vehicle sensing. We are looking for a highly motivated, dynamic and collaborative patent agent for our beautiful headquarters in Carlsbad. This is an opportunity to be a part of a small and growing team of world-class leaders in the next generation wireless and autonomous vehicle sensing industries, who are at the leading edge of the next wave of RF millimeter wave hardware, wireless applications, artificial intelligence, object detection, and machine learning. Metawave was founded in the iconic PARC campus in the heart of Silicon Valley. Our Carlsbad office is in close walking distance to the beach and has a fun and lively SoCal, start-up atmosphere.

Your Role:

Candidates must have excellent academic credentials, a willingness and ability to master complex technologies, and strong writing and communication skills. Candidate must be a confident self-starter, capable of working both on her/his own as well as part of teams. A broad background in many different aspects of IP is helpful, including prosecution, litigation, licensing, and/or transactions.

Responsibilities include:

- Work closely with Engineering team to identify patentable inventions

- Prepare and prosecute patent applications for Metawave core technologies

- Actively develop and manage patent portfolios

- Counsel technologists on protection of Intellectual Property

- Work with foreign counsel to protect innovations worldwide

- Collaborate with software and hardware teams to develop patent strategies for automotive radar and cellular communications

- Perform other duties as necessary for completion of projects and achievement of goals

Qualifications:

- M.S./Ph.D. in Electrical Engineering, Computer Science, or Physics

- Patent and Trademark Office registration required

- Ability to work in a fast-paced environment with technologists

- Outstanding writing and analytical skills, and top academic credentials are essential

- At least 5 years drafting and prosecuting high-quality, complex patent applications for major technology companies

- Ability to perform prior art searches and freedom to operate analyses’

- Writing samples and references required

Preferred:

- Experience in RF systems, including radar and cellular

- Experience in Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

- At least 3 years of working experience in industry

- For attorneys, at least one state bar registration

- German and/or Japanese speakers a plus

Perks + Benefits:

- Competitive salary package

- Stock options

- Full Healthcare Program (medical/dental/vision)

- Full Insurance Program (Life, Short and Long-Term Disability)

- 401(k) plan

- Free lunch & great snacks

- Fitness Reimbursement

- Flexible time off & paid holidays

- Social events + happy hours + team parties

Contact

To apply, please email us at: careers@metawave.co.

Additional Info

Employer Type: Small Corporation

Job Location: Carlsbad, California

Intellectual Property Associate / Patent Agent – Law Firm – Atlanta, Ga. or Austin, Texas

The Intellectual Property group of Eversheds Sutherland (US) LLP is seeking a patent agent or a second to fifth year associate with substantial experience in patent preparation and prosecution. Excellent academics are required. Candidate must be a member of the Patent Bar and have a degree in Electrical Engineering, Computer Engineering, Physics, Computer Science, or a closely related discipline. Relevant technological experience with semiconductor processes and packaging, wireless (preferably with 802.11) communications, consumer products, software, cloud computing, network technologies, wireless technologies, wireless communications, and/or consumer electronics is preferred.

The Intellectual Property group of Eversheds Sutherland (US) LLP is seeking a patent agent or a second to fifth year associate with substantial experience in patent preparation and prosecution. Excellent academics are required. Candidate must be a member of the Patent Bar and have a degree in Electrical Engineering, Computer Engineering, Physics, Computer Science, or a closely related discipline. Relevant technological experience with semiconductor processes and packaging, wireless (preferably with 802.11) communications, consumer products, software, cloud computing, network technologies, wireless technologies, wireless communications, and/or consumer electronics is preferred.

Contact

Please send a transcript with resume to LindsayYoung@eversheds-

Additional Info

Employer Type: Law Firm

Job Location: Atlanta, Georgia or Austin, Texas

In-House Counsel (Intellectual Property) – T-Mobile – Bellevue, Wash.

T-Mobile USA has an exciting opportunity for an In-House Counsel – Intellectual Property to be located at its corporate headquarters in Bellevue, WA. This experienced patent attorney, working in the T-Mobile Legal Department and the Intellectual Property team, will provide legal advice and support relating to patent procurement and general intellectual property matters.

T-Mobile USA has an exciting opportunity for an In-House Counsel – Intellectual Property to be located at its corporate headquarters in Bellevue, WA. This experienced patent attorney, working in the T-Mobile Legal Department and the Intellectual Property team, will provide legal advice and support relating to patent procurement and general intellectual property matters.

Responsibilities:

- Procure and manage company IP, including patents, trademarks, copyrights, domains and trade secrets

- Support the company's patent incentive program

- Team with company attorneys concerning patent procurement, intellectual property claims, technology licensing and litigation

- Create intellectual property policies and training materials

- Communicate and coordinate with European affiliates' IP counsel on global intellectual property policies and licenses

- Advise internal business clients and legal staff on company's intellectual property policies and general IP law and procedure

Requirements:

- Prior experience in drafting and prosecuting patent matters, as well as a demonstrated facility in reviewing patents and understanding highly technical conceptions across a wide variety of subject matters

- Law degree and 7+ years of legal experience, including patent prosecution and either patent litigation or technology licensing experience

- A technical degree in a relevant technology-related discipline, as well as law firm and previous in-house experience strongly desired

- Aptitude for, and a strong desire to obtain, a deep and broad knowledge of wireless products and services

- A demonstrated ability to recognize and weigh business and legal risks and to advance practical solutions

- Detail-oriented, with excellent verbal and written communication skills

- Customer-oriented interpersonal skills and a proven ability to excel working with multiple clients in a fast-paced environment

Benefits:

T-Mobile USA offers a full range of comprehensive benefits, including medical, dental, vision, as well as matching 401(k), generous paid time off programs, mobile phone and service discounts, tuition reimbursement, free parking – not to mention a fun and business casual work environment.

Additional Info:

Employer Type: Large Corporation

Job Location: Bellevue, WA

Contact:

For more information and to apply, please visit: http://www.t-mobile.com/jobs and reference Req #168832.

T-Mobile USA is a national provider of wireless voice, messaging and data services capable of reaching over 268 million Americans where they live, work and play. In a world full of busy and fragmented lives, we at T-Mobile USA, Inc. have the idea that wireless communications can help. The value of our plans, the breadth of our coverage, the reliability of our network and the quality of our service are meant to do one thing: help you stick together with the people who make your life come alive. That’s why we’re here.

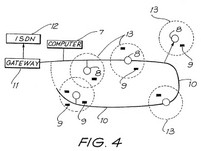

CSIRO v. Buffalo Technology (

CSIRO v. Buffalo Technology (